The names of top jazz soloists that never made the big time would fill a couple of books. Tina Brooks was just one of them, but he was let down not so much by public indifference as a failure on the part of those best known for helping establish young jazz musicians to promote him.

He was born Harold Floyd Brooks and named Tina, a corruption of the Tiny that reflected his diminutive stature. He recorded four LPs for Blue Note between March 1958 and March 1961. Only one LP was issued in his lifetime. The others came out much later – one from Japan in the 1980 and the other two in the late 80s, far too late to do Brooks any good. He died in 1974. Records with him as sideman appeared while he was alive, but he was only known in his lifetime as a leader on True Blue, his second LP. Fortunately it came to be considered by many to be his finest work.

Brooks was a unique tenor saxophonist who had a sound heavily inflected with the blues, a bit like his first main influence Lester Young, but not quite the same. He was also a bit like Hank Mobley but not quite in the same bracket. He was a fluid player, light sounding but swinging easily and he had in his head a group sound which began to take shape on the first LP session (1958), that was released in 1980 as Minor Move. That sound was almost fully realised on True Blue (1960). Had his four LPs been issued in sequence of recording it might have brought considerably more recognition of his unique talent.

Minor Move had a grade A cast of sidemen: Lee Morgan on trumpet, Duke Jordan (piano), Doug Watkins (bass) and Art Blakey (drums). It had a programme of three standards and two originals by Brooks. Nutville is a medium-tempo blues that showcases Brooks’ preaching, blues-soaked tenor sound ideally. He swings it compulsively throughout his own solo, setting the mood with his own sound and setting up Lee Morgan for the sort of flashy, stomping solo he was so good at. Sonny Clark is also key to the success of this and indeed all the tracks on this fine bop and blues LP, his downhome solos and carefully thought-out comping adding to the atmosphere that Brooks was busily trying to create. Watkins and Blakey were hand in glove on bass and drums, as they always were since the early, heady days of the first Jazz Messengers in 1955.

Speculation on why this record was not released at the time centres on the opinion that the ensembles were a trifle ragged. Blue Note boss Alfred Lion was certainly fussy about clean ensemble playing. But I doubt many buyers would have complained and my opinion is it was more likely an occasional and not very prominent blurred sizzle sound on Blakey’s cymbal that put the session on the shelf. I have the Mosaic set from 1986 which has the sizzle, but I am told that subsequent reissues have eliminated it with modern technology. The fact remains that this was one red-hot hard-bop disc as good as many and better than most that were released at the time.

True Blue (BLP 4041) was recorded 25 June 1960. Although perhaps not quite so distinguished in the jazz fraternity, the sidemen here were ideal for Brooks and his unique sound. Freddie Hubbard was then a bright, very young trumpeter who had worked with Brooks in clubs around Harlem and the two were extremely comfortable together. Duke Jordan was an instinctive pianist, free flowing and well versed in the blues, who had worked frequently with Charlie Parker, a specialist in the genre. Sam Jones and Art Taylor were veteran rhythm section players. The whole group were happy and able to present Brooks’ music the way he wanted to hear it – persuading the likes of Lee Morgan and Art Blakey to conform to Brooks’ ideas would have been much more difficult.

With tracks such as True Blue, Good Old Soul and Miss Hazel the Brooks band swing into a joyous call-and-response, gospel-flavoured blues sound that had his particular stamp in the ensemble voicings. Rendering mostly minor harmony, his voicings for horns with Hubbard had what American critic Robert Palmer described as “a lovely blend, with just a touch of haziness around the edges, an effect reminiscent of a photo that is deliberately and very slightly out of focus”. Palmer also suggested that on the track Miss Hazel, the two horn soloists varied it slightly “using both harmonized lines and passages of subtly phrased counterpoint”. The end effect was that by using tried and tested methods of blues expression but varying them in a personal manner, Brooks came up with his own distinctive sound. In his essay for the Mosaic release of this record, Palmer says that he considers True Blue a masterpiece. “Some nights”, he said, “it’s the only record I want to hear and the only record I play.” Certainly, as an example of heavily blues-flavoured hard bop it is as good as it gets.

Four months later, in October 1960, Brooks recorded an LP that was named Back To The Tracks and given a Blue Note catalogue number (4052) but never released by the company. What was Alfred Lion thinking of? He even put promotional images of the album on the inner sheets of other Blue Note records, so buyers could have imagined it had been issued. The more mischievous fans claimed to have seen copies of Back To The Tracks in record shops or said they knew someone that had a copy. Thus Brooks became famous for music that nobody had ever heard.

What a record they would have heard had it been released. Like True Blue in basic antiphonal form, for the most part it retained Art Taylor on drums but brought in a new and highly suitable crew in trumpeter Blue Mitchell, pianist Kenny Drew (two men well versed in the blues) and bassist Paul Chambers. Minor blues tracks were again dominant and on one Jackie McLean had a blazing solo along with Brooks. It was Street Singer, a title Lion had taken from another session featuring this combo but under McLean’s leadership.

Just listen to Brooks charging through the chords on The Blues And I. Meanwhile, Mitchell and pianist Drew were every bit as compatible with the leader as Hubbard and Clark had been on True Blue. Back To The Tracks was an almost perfect follow up to that record and had it been issued at the time it would surely have helped establish Tina Brooks as a first-rate tenor man bound for an impressive future. But it never saw the light of day until 1985.

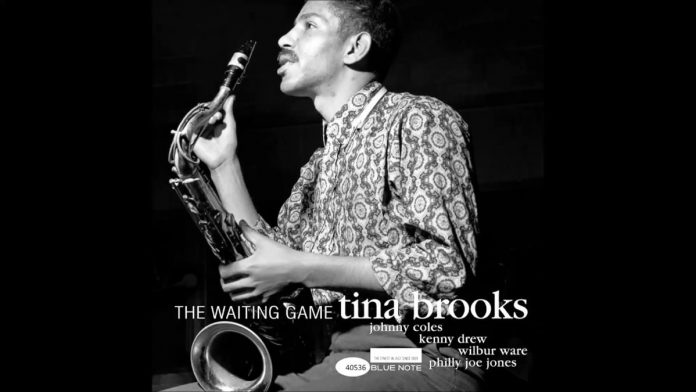

It’s curious that having failed to release Back To The Tracks in 1960, Alfred Lion put Brooks in the studio again in March 1961 and recorded what eventually came out (in the late 1980s on Mosaic) as The Waiting Game. This too is a solid swinger, a typical hard-bop session of the period but with an extra thick layer of blues. Here he has the first-class rhythm team of Drew, Wilbur Ware on bass and Philly Joe Jones driving hard behind him. Johnny Coles, with his warm, lyrical sound, might well be seen as the ideal trumpeter for a Brooks front line. Again, the ensembles have that slightly delayed sound and a unique Brooks unity. David The King and The Waiting Game are typical Brooks lines and have his personal stamp all over them. Stranger In Paradise comes over as a blues ballad; strong, passionate, pulsating.

Tina Brooks was a great player who never really had a chance to make it. Today he is better known than in his lifetime and two of his albums, Minor Move and The Waiting Game, are included in Blue Note’s high-profile Tone Poet series, an audiophile reissue programme of LPs just coming onto the market now. It could be that poor sales of True Blue was a factor in the non-release at the time of subsequent Brooks albums, but from an artistic perspective posterity has shown that the other three albums deserved to be issued.

Tina Brooks never recorded again after 1961. He managed to scrape a few gigs in the Bronx at small clubs and went on one tour with the Ray Charles orchestra. He died 13 August 1974 at the age of 42. He had been unwell for some years and unable to play the saxophone. Jackie McLean described him as a sensitive human being and brilliant musician who was crushed under the pressure of the industry. Another musician described his demise as the result of general dissipation.

Towards the end of his Mosaic essay Robert Palmer suggests that Brooks might have had a better chance if more people had been listening. He said that the more we are bombarded with the same lowest-common denominator music, the less we listen. While there is still enough good music to listen to we should tune in to Tina Brooks.

Acknowledgements

The Complete Blue Note Recordings Of The Tina Brooks Quintets (Mosaic MRS 106)

Essays in the same set by Robert Palmer & Michael Cuscuna

Sleeve notes by Larry Kart and Ira Gitler