Tony Kinsey recalls how fellow drummer Phil Seamen invited him to his flat to listen to a new record, probably a tape from America played on his giant Grundig recorder. After coffee, Seamen changed into his pyjamas, popped some pills, and went to sleep. “That’s the sort of thing that sometimes happened to Phil,” Kinsey says. “He wasn’t like that when I first met him; he wasn’t like that at all.”

He certainly wasn’t. Lots of jazz musicians have taken drugs and lots have become hooked. Seamen, hailed by many as Britain’s greatest jazz drummer, was a junkie, almost the storybook emblem of one, the epitome of a jazz cliché. Drugs both inspired him to zeniths of creativity and fogged his progress. That he survived to his mid-40s was a grudging gift to music from the sportive gods.

In his massive book about Seamen, Peter Dawn laments that his subject is not formally remembered, not even in his birthplace of Burton-on-Trent or at the famous Golders Green Crematorium, where his ashes were scattered 50 years ago amid memorials to far less worthy shades. Dawn shows how much information was out there just waiting to be collated and how many who knew Seamen were only too willing to recollect, Kinsey among them. There’s probably more, to judge by the amount he did gather, let alone what must exist pertaining to other jazz musicians and their colourful lives. Jazz has a plethora of them.

Phillip William Seamen died in his London flat on 13 October 1972 not long after steeping out of a railway carriage on the wrong side at a station and falling on the electrified track. That didn’t kill him. He was taken to hospital but he discharged himself. The cause of death was barbiturate poisoning. It was a coroner’s conclusion but in a book stuffed with quotes from more witnesses and interviewees than any reader could ever require, it’s Stan Tracey who explains with a user’s deadpan matter-of-factness how tooties gulped to excess pile up in the body to lethal levels.

Seamen was an odd one. Of the countless vivid episodes recorded in the book, the following stands out: a group of UK musicians are walking along Soho’s deserted streets in the early hours with Stephane Grappelli when Seamen suddenly appears, making his way towards them. He recognises Grappelli and says he’s going to turn up to perform where the violinist is playing and insert his drumsticks in a part of the sanguine Frenchman’s anatomy. (Grappelli, though he never “came out”, was widely thought to have been gay.) The book is testimony to how mega-talent can be pleaded as unacknowledged atonement for the ill-mannered and outrageous. And Seamen was mega-talented.

It’s worth beginning a summary of Dawn’s heavyweight tome with this seediness and bathos, to which Seamen was prone. But he was as cool, witty and sarcastic as his sometime band colleague Ronnie Scott and many other jazz musicians. According to Tom Burton, whose wife Peggy had been married to Seamen’s trombonist associate Ken Wray, the drummer was “an aggressive and unpleasant individual although sometimes he could be quite charming”. It’s a common enough dichotomy of personality when you are on booze and drugs. Art Themen notes that (to paraphrase) everyone wants to buy drinks for a jazz celebrity.

Like alto saxophonist Peter King, Seamen had polymathic tendencies. He showed a keen interest in modern literature, according to the late avant-garde music promoter Victor Schonfield. Organist Alan Haven said Seamen was “particularly well read and had an incredible knowledge”. Dawn himself implicates the drummer, when a member of the Joe Harriott quintet, in signposting the music’s history, despite being conspicuous by his absence in lists of the world’s top jazz drummers: he believes in the commonly expressed idea that free jazz was founded and developed at the same time in the US and UK by Ornette Coleman and Harriott.

Seamen often decamped to his home town at a moment’s notice, or no notice at all, when the London jazz life tore into him. Most jazz lovers have no idea what such a life is like. During the period essayed in this book, it’s an almost masonic fraternity in which women seem to have no place except as paramours or domestic props. Now and then they sing into a microphone. But, after reading hundreds of Dawn’s attestations, one begins to get a sense of how closed a society it is. Jazz, a minority interest with a universal reach, is always embattled. It’s to Dawn’s credit that his book invites entry to the jazz musician’s world, in this case a voluble one.

Seamen’s career is logged in great detail, from his time playing in Locarno-type dance bands led by Joe Loss, Jack Parnell and others to his small-group collaborations with, inter alia, Joe Harriott, Scott, Tubby Hayes, Ginger Baker, Dick Morrissey and Harry South. He courted the parallel rock world – Charlie Watts wrote the book’s glowing foreword – and everyone, especially his American contemporaries such as Louis Bellson, Buddy Rich and Shelly Manne thought hugely of him. So did visiting Stateside musicians with whom he played, among them Sonny Rollins and Roland Kirk. When Kenny Clarke needed a dep on the kit in Paris, Seamen was first call. He was Leonard Bernstein’s choice as pit-band drummer for the London opening of West Side Story.

He knew his stuff, as they say. Chapter 23 is devoted to Seamen’s views on the art of drumming, with his own notated exercises for one of his pupils, Rod Brown, and illustrations of practice runs taught to Ginger Baker. The former have handwritten notes, presumably by Brown himself, and the latter incorporates an onomatopoeic drum pattern called “Mummy Daddy Paradiddle”. To add to Seamen the master’s darker side, Baker the pupil described himself as “a bit of a monster”. So much is well known. If you’re a drummer who’s learning, you might like to know that Dawn includes covers of all 48 albums on which Seamen is known to have played, with everyone from Acker Bilk to Zoot Sims and taking in Tony Coe, Vic Feldman and Memphis Slim.

Bearing in mind the industry and midnight oil involved in its production, Dawn’s well-written book makes the reader more charitable than critical. Like many self-published ventures in non-fiction by non-professional writers, the temptation to include the minutiae of research instead of selecting from it and rejecting the rest must have been difficult to resist. Poles and perches of text could have been cut without loss and would have resulted in a more manageable but no less captivating read. That said, the book’s length and forensic detail make it both encyclopaedia and hagiography, though the portrait rightly includes its subject’s flaws. The notes and references section forms a whopping 144-page appendix and includes an index, always a mark of the writer’s responsibility and devotion to duty.

Dawn has no background in jazz and was aided and abetted throughout by jazz writer and drummer Chris Welch, who knew Seamen. Dawn worked in the nuclear and polymer industries and ran his own company. Coming from Seamen’s birthplace, he wrote the book as “an interesting and worthwhile” project in retirement. No doubt musicians who remember, or think they know, the acres he surveys will scrutinise them and home in on solecisms. But there’s no doubting the author’s grit and passion. Getting to the end of his book is like reaching the final course of a hearty but meticulously prepared dinner.

Ian Carr in conversation with Alyn Shipton describes Seamen as “a very extraordinary human being because he was very . . . sharp mentally, funnily enough, despite all the drugs”. Seamen and drugs were synonymous but so were Seamen and superlative jazz drumming. Dawn flinches from neither comparison in refusing to exclude the difficulties the former posed to the musician himself and those alongside him and in making sure his stature and reputation are covered in all their farthest reaches. The book’s been a major undertaking and deserves a place in the National Jazz Archive as well as on the shelves of public libraries, not least the one in Burton-on-Trent.

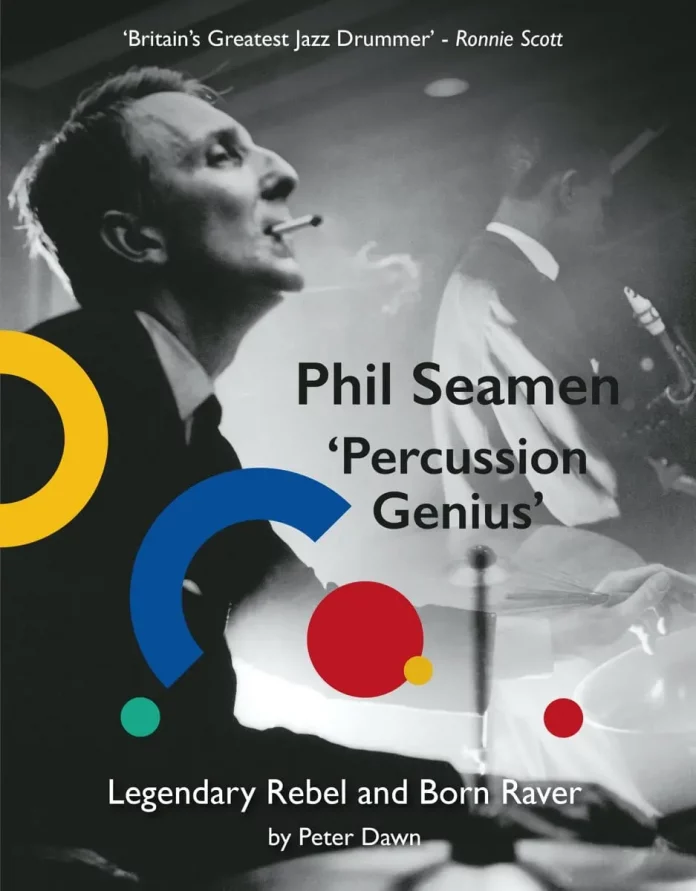

Phil Seamen: Percussion Genius, Legendary Rebel And Born Raver, by Peter Dawn. Self-published by the author as Brown Dog Books, hb, 751pp, £45 plus postage/packing from peter@peterdawn.co.uk or philseamen.com. The latter website, created by the author, contains over 100 remastered and downloadable tracks on which Seamen played.