Harold’s reliable presence on the club scene brought him to the attention of local recording companies, notably Vee-Jay, where he established himself as one of the house drummers for the label. In 1961, he helped Eddie Harris make jazz history when his Vee-Jay record Exodus To Jazz became a surprise hit.

Jones recalls: “We went in for the recording date, and we had four, five, six tunes, and it wasn’t enough for the album. Eddie said: ‘Well, I got some movie scores here.’ So we did that, and the tag on the song was almost longer than the song, but that was part of the song. And then that became the hit – it was unreal.”

I asked Jones if he had shared in the windfall, to which he answered: “I got two hundred dollars and ran out the back door.” The benefits for Harris, however, were life-changing: “He got married to the prettiest girl on the south side of Chicago, bought a big new house, and bought a German Shepard and named it ‘Exodus’!”

Other notable associations during this busy period included a stint in an early version of the Paul Winter group. He also worked and recorded with underrated alto saxophonist Bunky Green. Though not widely known to jazz fans, Green inspires reverence among musicians: “He’s a hell of a saxophonist! I played in a band there with Willie Pickens, Bunky Green and Donald Garrett, and man, it was swinging!” Harold’s work with Green can be heard on a CD compilation called Playin’ For Keeps. He plays on six tracks, recorded in January 1966, that showcase Green’s bluesy, searing sound, deep groove and masterful improvisations.

A year after these tracks were made, in 1967, Jones joined Count Basie for a two-week job that stretched into five years. He explains: “When they called me, the drummer was Rufus Jones. Duke came up with an emergency gig in the Far East, and he needed to leave town immediately. So he called Rufus Jones, and Rufus went to the Far East with him. I guess the gig turned out to be two or three months before they came back.”

Upon joining the Basie band, Harold found himself locked into a rhythm section that purred like a Rolls Royce: “It was over the rainbow, man. As a drummer, because of the strong rhythm section swinging together, you can’t do anything wrong, nothing sounds wrong because it’s all so tight. If you do something, it just sounds like a great ad lib.”

Being Basie’s favourite drummer: ‘I was very proud of that. He told me: “Even though you’re not the leader, you’re the governor” . . . If I hit my accents right, then the band would hit theirs right’

Harold joined as the Shiny Stockings and Atomic Basie sound was giving way to a new approach with fresh arrangements from Sammy Nestico and others. In a band that had no weak links, the sax section stands out, indicating just how loaded with talent this organisation was: Bobby Plater, Marshall Royal, Eric Dixon, Charlie Fowlkes, and of course, one of the great saxophonists in jazz history, the brilliant Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis.

Harold soon became indispensable to Lockjaw, known as a kind of roving jazz gladiator, forever in search of a jam session and itching to take on all comers: “Every city that we went to, when we didn’t have a bus ride after the show, Lockjaw would find out where the jazz club was. And he would call me to go with him because . . . the bands were usually kind of good, but the drummers weren’t that good, so he’d take me just so he knew he had support. I went with Lockjaw to jam sessions in every city for five years.”

Harold contributed to some 15 records with Basie, one of his favourites being Send In The Clowns, with Sarah Vaughan. I asked him about having been named Basie’s favourite drummer. “I was very proud of that. He [Basie] told me: ‘Even though you’re not the leader, you’re the governor’ . . . It was kind of like I was running the show and responsible for keeping that band together. If I hit my accents right, then the band would hit theirs right. Anyway, I was running the show, once they gave me the ball [laughs].”

Being catapulted to the highest possible perch as the one who ran Basie’s show seems like a prelude to a fall from grace, or at least a reality check. But not for Harold, who continued to excel and to move forward in his career. Thanks largely to those five years with Basie – who worked with all the great vocalists – Harold earned a reputation as the singer’s drummer after he and the Count parted ways.

A partial listing of those who benefited from his talent, experience and good taste includes Ella, Sarah, Carmen, and among those perhaps requiring two names: Nancy Wilson, Kay Starr, Ernestine Anderson, Ray Charles, B.B. King, Joe Williams, and Sammy Davis Jr. (Incidentally, Harold told me he didn’t work with Sinatra, but he did play drums at is house in Palm Springs, and hung out with him.)

“It was all good. Ella had a good trio – it was Tommy Flanagan and Keter Betts,” Jones remembers. “Nancy Wilson carried Harold Land and Blue Mitchell, and once when she went to Japan, she took Joe Williams as a second singer.” In the 90s, he toured and recorded with Nat’s daughter, Natalie Cole, as part of her resurgent career. As had happened with Eddie Harris, Harold contributed to a hit record when Cole’s 1991 tribute to her famous father became a smash success. Though Jones did not play on the title track of Unforgettable, he supplied rhythm for more than half of the songs on the album. In the early 2000s, Harold became part of Tony Bennett’s show, working with the singer to the end of his career. “I did the last 15 years, right up to his last job.”

Throughout these years backing high-profile singers, Jones worked in education, introducing young players to the great jazz tradition he had helped create. He also remained active in the studios and on stage, playing and recording with people like Oscar Peterson, Herbie Hancock, Ray Brown, Scott Hamilton, Herb Ellis, Walter Norris and others.

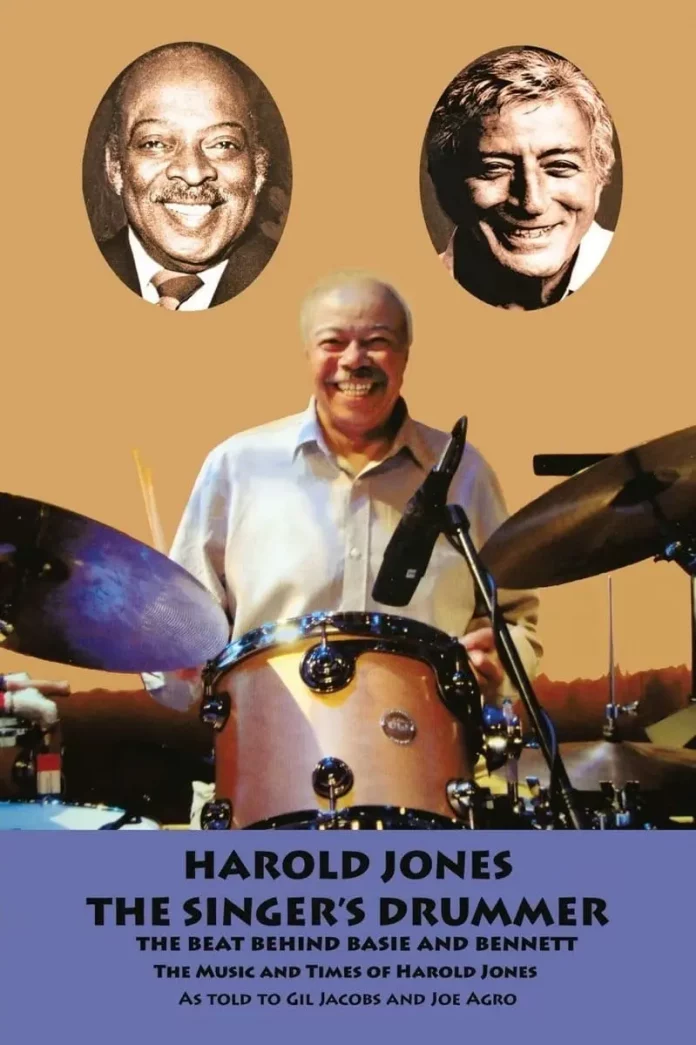

Many more entertaining stories – such as of Jones being among the first to introduce jazz to the White House with the Paul Winter group while President Kennedy and his cabinet confronted the Cuban Missile crisis, or of appearing with Basie in the middle of the desert in the motion picture Blazing Saddles – can be found online. Those seeking more information might also want to consult Harold’s 2011 autobiography, The Singer’s Drummer.

Beginning as a teenaged professional working with Wes Montgomery, then becoming Basie’s favourite, and finally building a reputation as the singer’s drummer, Harold Jones has charted a remarkable career. Though he remains unrecognised by many fans of the music, discerning players know and revere him. Perhaps he deserves yet another label to honour his nearly seven decades of achievement: The Musician’s Drummer.

Thanks to Jean-Michel Reisser for ferreting out contact information for Harold Jones.