When Al Jennings travelled to Port of Spain in 1945 to recruit musicians for his Caribbean All-Star Orchestra, he returned to London with trumpeter Wilfred “Pankey” Alleyne. After several years playing in Europe, including a residency on the French Riviera and working in Mayfair clubs with pianist Clarie Wears and Tito Burns, Alleyne lost his job through his passion for cricket. After a game overran, he turned up late for a gig still in his whites to be told by the management “Don’t bother to get changed”.

‘Sorry to bother you, but we’ve come to see the cricket and the ground is full. Could we watch from your window?’

Alleyne had played for the London West Indian Team as well as clarinettist and bandleader Sid Phillips’ Xl, and decided to follow the example of fellow Trinidadian Learie Constantine into professional club cricket, by joining Fleetwood in the Ribbledale League, in 1950. According to Wisden, “he proved entertaining with bat, ball and (in the bar afterwards) trumpet”. Heart trouble eventually forced him to give up the trumpet but continued playing amateur cricket until he was 66.

Calypso was to gain great popularity, especially after West Indies’ victory at Lords in 1950, although it acknowledged jazz in Lord Kitchener’s Kitch’s Bebop Calypso, (Melodisc 1162) which mentions Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. Producer Denis Preston used a more varied musical combination than the usual calypso instrumentation, including the Jamaicans Bertie King (cl, as), Clinton Maxwell (d), Freddy Grant (cl, ts), Neville Boucarut (b) and Fitzroy Coleman (g) and Guyanese pianist Mike McKenzie. Like Grant, both King and Maxwell had participated in the pre-war black music scene in London, the latter two having played together in Jamaica before migrating to Britain.

In his book Jazz In Revolution (1998), John Dankworth wrote that amongst his contemporaries at school was Doug Insole, later of Essex and England and author of Cricket Notes for Jazz Express, the Pizza Express in-house magazine. Dankworth frequently visited Lords to watch Middlesex, sharing this interest with other members of his band, notably bassist Joe Mudele. When arriving at Lords to see England play West Indies, and seeing the house-full notice, Mudele singled out a block of flats flanking the ground, marched up several flights of stairs and knocked on a random door, saying “Sorry to bother you, but we’ve come to see the cricket and the ground is full. Could we watch from your window?”

“I marvelled with some embarrassment at Joe’s impudence”, recalled Dankworth. “We all trooped in to a sea of welcoming faces and we spent the whole of that day – and the next – enjoying a grandstand view of the action”.

A contemporary of Dankworth was Benny Green, who played saxophone with Ralph Sharon, Ronnie Scott, Stan Kenton and Dizzy Reece. He also had a great interest in cricket, writing about it and editing the Wisden Anthologies, summaries of the famous cricket annual. Another musician to play with Dankworth was Guyanese singer and percussionist Frank Holder, a keen cricketer who played for Vic Lewis’ Celebrity teams and for the Ravers C.C.

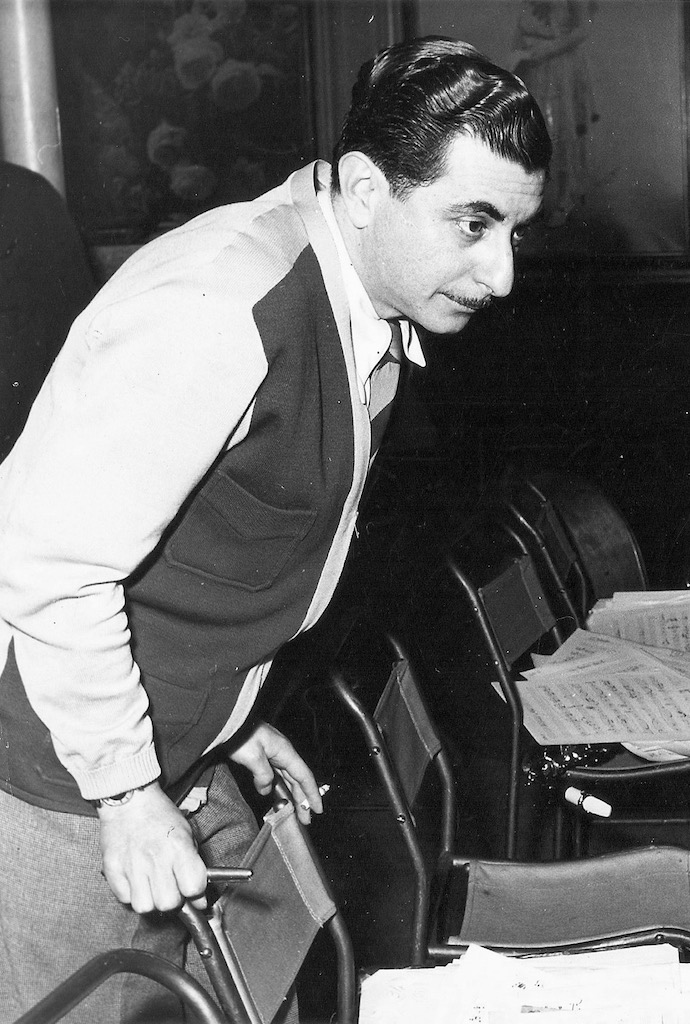

Vic Lewis

Vic Lewis was regarded by some for his braggadocio – but his stories often turned out to be true. His father, a spin bowler for Kent 2nd team, gave his son an interest from an early age. After forming his Swing String Quartet in 1935, working with Carlo Krahmer, George Shearing and even Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli on one of their London visits, guitarist Lewis visited Leonard Feather in New York, whom he knew from the No.1 Rhythm Club in London.

Through Feather he met and played with Joe Marsala, Buddy Rich and Joe Bushkin at the Hickory House, as well as guesting at clubs with Pee Wee Russell, George Wettling, Sidney Bechet, Zutty Singleton and Wellman Braud, and sitting in with Tommy Dorsey, Jack Teagarden and Louis Armstrong.

On his return to London he formed the Vic Lewis Orchestra, playing at the Paris Festival of Jazz in 1949 on the same bill as Gillespie, Parker and Davis. His band included Kathy Stobart, Ronnie Chamberlain and Hank Shaw. Heavily influenced by Stan Kenton and Gerry Mulligan, he recorded Music For Moderns in 1950 and employed many of the young British musicians during that decade. On the album Mulligan’s Music (1954) arrangements were adhered to, but soloists given the opportunity to express themselves, notably trombonist Johnny Watson and the young Tubby Hayes, whose baritone solo on Bark For Barksdale is an indication of things to come, when he would build solos like a batsman compiling an extended innings.

Lewis also founded the Vic Lewis Cricket Club, which featured showbiz celebrities and cricketers and raised money for several charities. As an agent and manager, Lewis was known to take visiting artists to matches – a photo in Lewis’s book Music & Maiden Overs shows Gerry Mulligan and actress Sandy Dennis at Mill Hill cricket ground and Nat King Cole’s visit to Lord’s was accompanied by the singer being presented with a cricket ball by West Indian captain Frank Worrell.

George Shearing

For many years, pianist George Shearing and his wife relocated from his New York home to Stow-on-the-Wold in the Cotswolds for a few months each summer. Here he would listen to Test Match Special on BBC Radio and when cricket commentator Brian Johnston heard of this, he invited Shearing to the 1990 New Zealand Test match at Lords and interviewed him for View From The Boundary. Johnston had met Shearing once before, at Fischer’s Restaurant in London in 1946, when Shearing was with the Frank Weir Band and Johnston was broadcasting Saturday Night Out.

George Shearing: ‘As a kid I used to go out in the street and play cricket with sighted people. Sometimes I hit the ball and sometimes it hit me’

Shearing described his life in the Linden Lodge School for the Blind, Wandsworth, where he attended between the ages of 12 and 16 and where he played cricket, at first with a large balloon-type ball with a bell in it (he was later to joke “you needed the bell for the shortsighted”), underarm bowling and a wicket made of wooden blocks and plywood. He recalled that “As a kid” [in Battersea] “I used to go out in the street and play cricket with sighted people”, with him holding the bat helped by one of the local boys. “Sometimes I hit the ball and sometimes it hit me”. When imagining the play, Shearing admitted to having only vision of light and dark, but sitting in the commentary box “it’s an interesting aspect of controlled acoustics and wonderful daylight”.

He would have to imagine the proceedings: “Two things that a born-blind man would have difficulty with are colour and perspective”, but his education and instruction had given him the information to deal with spatial issues. After his knighthood ceremony in 2007, he hosted a luncheon for close friends including fellow cricket enthusiasts Michael Parkinson and John Dankworth. (To be continued)