This summer sees the series of cricket matches known as The Ashes played between England and Australia and it reminded me of one day in 2013, when a small group of us left the Magdala pub in Hampstead to scatter the remains of writer, former agent and long-time editor of house magazine Jazz At Ronnie Scott’s, Jim Godbolt. On our way to the heath I noticed clarinettist Wally Fawkes had an earpiece plugged into a radio, and asked him what he was listening to. “Cricket”, he appropriately replied, “The Ashes”.

The links between cricket and music have been written about at some length, particularly by David Rayvern Allen, whose book A Song For Cricket is a comprehensive account covering the earliest references, through Victorian and Edwardian eras to the present. Calypso, understandably, is also well covered but little has appeared to document the affinity between cricket and jazz.

Neville Cardus described the batting of George Gunn as like ‘Louis Armstrong playing in the Philharmonic Orchestra while a symphony by Mozart was being performed’

The two activities have common elements – technical expertise and skill in playing, interaction with fellow players and response to their contributions, plus the opportunity for individual expression and improvisation within a structured context. In issue number 3 (1982) of the music magazine Collusion, pianist & saxophonist Jez Parfett extolled the virtues of the cricketer Kumar “Prince” Ranjitsinhji, making this connection. Writer Neville Cardus described the batting of George Gunn (1879-1958) as classic elements mixed with modernity and unorthodox improvisations, like “Louis Armstrong playing in the Philharmonic Orchestra while a symphony by Mozart was being performed”. Writing for the Manchester Guardian in the 1920s he saw Cecil Parkin (1886-1943) as “the first jazz cricketer – his slow ball was syncopation in flight”. More recently, Antiguan activist and journalist Tim Hector wrote that West Indian batsmen Gary Sobers and Rohan Kanhai “embodied what can really be termed the satyric passion for the expression of the natural man, bursting through the restraints of disciplined necessity. Both showed the creativity of the great jazz musicians in their marvellous improvisations”. Hector regarded improvisation in jazz as the innovation in 20th century music.

Many took a keen interest in both, one of the first being Maurice Allom, who as a student played cricket for Cambridge University, from 1926 to 1928, and during this time played clarinet and saxophone with Fred Elizalde and his ’Varsity Band, making several recordings in 1927, although the jazz content was limited. A better cricketer than saxophonist, Allom played regularly for Surrey and became the first bowler to take a hat trick (three wickets in three successive balls) for England on his Test debut against New Zealand in 1930 and in fact took four wickets in five deliveries – the first instance of this happening in a Test match. He later went on to become president of the M.C.C.

Another cricket-playing Cambridge undergraduate (albeit briefly) was Patrick “Spike” Hughes, who played for minor counties team Cambridgeshire in 1926 and whose band the Decca-Dents included clarinettist and saxophonist Harry Hines, later to umpire charity cricket matches. As a successful musician, Hughes introduced American jazz musicians to his band, notably Jimmy Dorsey, before moving to the US, where he stayed with music critic and producer John Hammond and recorded as Spike Hughes and his All American Orchestra, which had Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins, Red Allen and Dicky Wells amongst its members. Hughes stopped performing in the 30s, but wrote as “Mike” for the Melody Maker, during which he continued to play cricket for club sides and charity matches for the Lords Taverners. “One of my proudest cricketing moments is of capturing the wickets of both Flanagan and Allen in one innings. This is undoubtedly a record”.

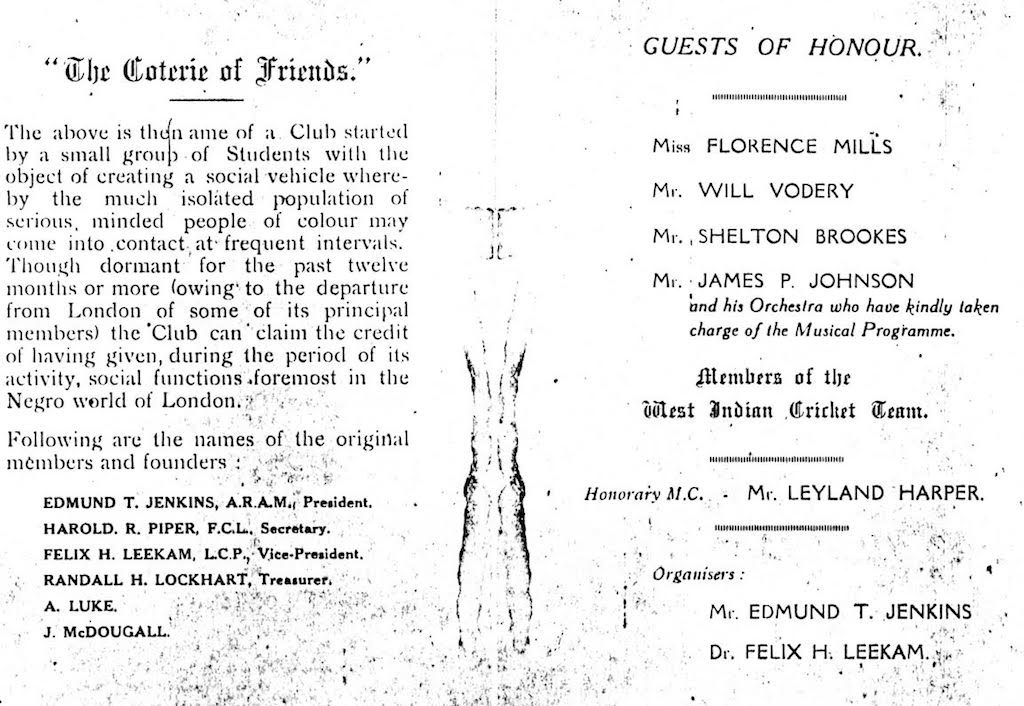

The first apparent link between jazz and West Indian cricket began in 1923 with the gathering of a group in London known as the “Coterie of Friends”. Founded in 1919 by American clarinettist and composer Edmund Jenkins, its purpose was to create “a social vehicle whereby the much isolated population of serious minded people of colour may come into contact at frequent intervals” (Coterie of Friends programme notes – see illustration below, courtesy Howard Rye). Sunday 13 May 1923 saw a social evening at the Adelphi Hotel, London in which the guests of honour included the singer Florence Mills and pianist James P. Johnson, an eminent and influential figure in early jazz, who were in London for an extended period in the Afro-American Plantation Revues. Johnson’s orchestra (with future Duke Ellington bassist Wellman Braud) had “kindly taken charge of the Musical Programme”. Also as guests of honour were members of the West Indian Cricket Team, who had arrived in late April and included the young Learie Constantine.

In the 1930s, Jigs Club, run by Alec and Rose Ward and George “Happy” Blake in Soho’s Wardour Street, served as a sports and social club for the Afro-Caribbean community as well as a music venue. Its visitors included Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway and others. In 1933 the British West Indies Cricket Club players were met on their arrival at Tilbury by members of the club, invited to dinner, “in honour of their visit” according to an entry in the day book, and made honorary members, as were Duke Ellington and his band, during the extent of their stay in the country. The Ellington Orchestra recorded four sides for Decca at the Chenil Galleries, Chelsea in July of that year (Hyde Park, Harlem Speaks, Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Chicago).

The West Indian team included Jamaican batsman George Headley, one of Wisden’s Cricketers of the Year for 1934 and Trinidadian Clifford Roach, whose 180 against Surrey in 170 minutes was described by Wisden as the most dazzling innings on the tour, Roach scoring a century before lunch.

Bandleader Sam Manning, in the country at the time, and bassist Al Jennings, both from Trinidad, would no doubt have been interested in the team’s progress, as would trumpeter Leslie Thompson, who was a leading figure in London’s Caribbean jazz community and a cricket enthusiast. Later, Trinidadians Carl Barriteau, George Roberts, Dave “Baba” Williams and Dave Wilkins, were all recruited into the Thompson/Ken “Snakehips” Johnson’s band. According to writer Val Wilmer, Wilkins was particularly interested in cricket, both watching and playing.

Jigs Club also had its own cricket team which played against bandleader Harry Roy’s Xl that year, though minutes of the meeting stipulated that it had to be “members of the Musicians’ Union only”. A letter of welcome was again sent to the West Indian Cricket Team for their tour of 1939, during which Calypso And Other West Indian Music, presented by Johnson, was broadcast on BBC London regional service. A regular at Jigs around this time was the Trinidadian trumpeter and younger brother of George, Cyril Blake, who recorded Cyril’s Blues (Regal Zonophone MR 3597) with Laurence Caton on guitar, live at the club on 12th December 1941.