This is one of a series of taped interviews with musicians who are asked to give a snap opinion on a set of records played to them. Although no previous information is given as to what they are going to hear, they are, during the actual playing, handed the appropriate record sleeve. Thus in no way is their judgment influenced by being unaware of what they are hearing. As far as possible the records played to them are currently available items procurable from any record shop.

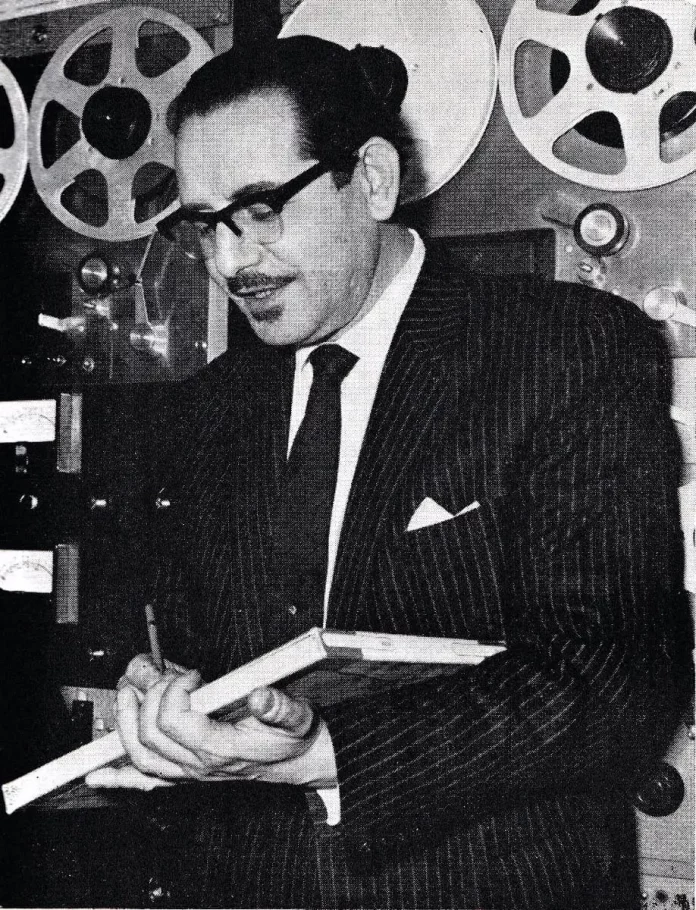

Denis Preston has for some years now been the major producer of British records, and was fortunate, or far-seeing, enough to have been the man behind most of the jazz records to make the Hit Parade. It is something of a paradox therefore that although undoubtedly this man’s heart lies with the real and genuine jazz of the thirties, he owes his success to that somewhat spurious music known as British Traditional jazz, and to a lesser extent to his fostering of the music of the West Indies. But his interest in the genuine article has never lessened. He has a keen insight into what is right and what is wrong with jazz, and most certainly knows the good from the bad. For the sake of the music itself it was perhaps a pity Denis did not let loose his considerable talents and business flair upon America, the real home of jazz. For if he had there is little doubt that the lot of American musicians and the music itself might have benefitted considerably. – Sinclair Traill

Purple Gazelle. Duke Ellington-Afro Bossa. Reprise R 6069

Very delightful, but very disappointing. The chord sequence is very familiar, but I can’t for the moment place it. The voicing I heard years ago—it’s Dallas Doings all over again, the derby-hatted brass versus saxes. Beautifully played, but disappointing. It’s strange that Bossa Nova, which is something new and exciting rhythmically, hasn’t coaxed more than this from Duke. Everything he does, of course, has its special delights, but I would have expected better in the circumstances. This is just a potboiler.

To put it bluntly, Duke can be (and often is!) musically indolent

To put it bluntly, Duke can be (and often is!) musically indolent. I think he’s been particularly lazy with this record. I remember that during his last tour of this country he kept announcing his latest album for the Reprise label as if it were a bit of a joke. On hearing this track from it it seems to me as if that’s how he treated it!

The Trot. Bill Basie-The Legend. Columbia SCX 3471

It is hard to judge any album by one solitary track, and I haven’t heard the rest of this one. But I think I prefer the Basie band playing Neal Hefti arrangements—a funny thing to say because Benny Carter has always been one of my “greats”. And another funny thing. You’ll remember that very early in the thirties Duke Ellington recorded a piece called Jazz Cocktail, written and arranged by Benny Carter. Well, it didn’t sound like Duke, neither did it sound like Benny Carter. And I have the same feeling here. We’ve got the best big band jazz ensemble sound in the world—the dynamics on this are fantastic, perfect—but somehow it just misses, for me, the vital spark. That last chorus was unquestionably “old hat”.— back to the early thirties with Devil’s Holiday and all those Benny Carter things. There are so few good big bands records these days that I will probably buy it, but I doubt if I’ll ever love it.

I honestly think that this is the most boring piece of blues playing I’ve heard in years

Blues For Big Scotia. Oscar Peterson-Bursting Out With The All Star Big Band. Verve SVLP 9029

I see from the sleeve that it took them five sessions to make nine tracks—of which that was one. Well, all I can say to that is that someone must have more money than I have, and a great deal more faith in Oscar Peterson. I honestly think that this is the most boring piece of blues playing I’ve heard in years. And, considering the talent in the studio, what a shocking waste. The band never got a chance. Ray Brown and Thigpen were marvellous, but Peterson, with all his technique, just churns it out like a hurdy-gurdy. I’m nearly always moved by blues, but there’s no inspiration here at all; nothing to move me in any way. And it took five sessions to produce five titles like that! I’m sorry, I’d like to be complimentary but to me it was just a waste of time and money.

Bill Evans has technique, and to spare, but there’s no message in his playing

What Is This Thing Called Love? Bill Evans. Riverside RLP 12315

Well, this is a hard one. I would put Bill Evans in a kind of hinterland, somewhere between André Previn and that chap with the quartet—Dave Brubeck. He impresses me without moving me. The first time I ever heard Bill Evans was in the company of a musician I much admire—Ram Ramirez, about three years ago in New York. I felt then as I do now, that though the musicians were raving about him—as they tend to do about every new talent that crops up, he did nothing to me. His playing is clean, very athletic, but without warmth. I’m inclined to wonder what would happen if they replaced Brubeck with Bill Evans in the former’s quartet. I think the quartet would be the better for it, for although Evans plays in roundabout the same idiom he’s a much better pianist than Brubeck will ever be. Without being crow-jim in any way, they’re both very much “white” pianists. Bill Evans has technique, and to spare, but there’s no message in his playing. I wonder what this would sound like without bass and drums? Nothing much, I suppose.

I see from a recent Top Hundred listing of best-selling American albums that Horowitz has a new record breaking through. And it won’t be his first best-seller among the pops. Well, that may seem a bit irrelevant, except that I rather suspect that if I want virtuoso piano playing I’d choose Horowitz before Bill Evans at any time. If it’s jazz I’m after then I would still turn to Earl Hines or even Fats Waller. Among the modernists there are people like Wynton Kelly and Junior Mance, but their background is the blues, and I cannot believe that Bill Evans has one blue feeling in his whole make-up.

Mamie’s Blues. Jelly Roll Morton. Riverside RLP 140

At the risk of sounding even older than Brian Rust, this is the best record you’ve played me so far. It suffers from bad recording, and it’s a tragedy that so much of Alan Lomax’s stuff was so badly recorded—unnecessarily so, I think. He so often seemed to be so carried away by what he was recording that he didn’t trouble to take it down properly for posterity. This is fabulous material, but because of what I’ve just said it is, in places, very difficult to listen to with one hundred per cent pleasure.

How very different this is from what we might call his “commercial” version of the same piece: here he features that habanera bass, very much forward throughout. Whether this pre-dates Jimmy Yancey I wouldn’t know. I think a lot of those old boys were inclined to pick things up along the way and pretend—or imagine—they’d invented them. Like Bunk Johnson’s When The Saints on Victor many years ago, on which he played the Louis Armstrong improvisation. Now, as it was made after Armstrong’s own recording of the tune it raises the question in one’s mind, did Bunk hear Louis and indeed copy Armstrong’s chorus and then say “I invented it and Louis copied me!”? The same with this. It has a strong Yancey “feel”, and one doesn’t rightly know or not whether Jelly heard Yancey, copied him, and then said “This here’s the Spanish Tinge!”

But the thing has quality. It’s not terribly well played, but it has atmosphere. And I think it is an important record-— important being in inverted commas. It had meaning to the man who made it, and it doesn’t sound like a record made for a session fee at the end of three hours. I don’t know if the Library of Congress actually paid Morton anything, but this is definitely not a commercial record in any way. It was made because the artist involved had something to say and just had to say it! And when so many things are forgotten it is something that’s going to stay said forever.

Here is about the most inept rhythm section I’ve heard in my life. The drummer is diabolical…

I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None Of This Jelly Roll. Louis Armstrong plays Joe “King” Oliver. Audio Fidelity FBL 145.004

In some ways this is an important record; almost an historic record. But not because it’s a good one. Just the reverse. I’d like to have it, not to play for my own pleasure but to use as an example when people say to me, as they often do, “The real let-down in British jazz performances are the rhythm sections.” For here is about the most inept rhythm section I’ve heard in my life. The drummer is diabolical and can’t even hold the tempo, and the bass player is a nothing. I remember I heard this band in performance and thought then that it’s one of the worst Louis has ever led. Peanuts Hucko is accomplished, but achieves little; Kyle and Trummy Young are all right—and that about sums it up. Louis forgets his lyrics, which may be funny—and a good anecdote for jazz books of the future—but to me it’s just unprofessional. Of course it does show that even now when past his best Armstrong is still the best Dixieland or New Orleans lead trumpet. One intriguing thought though. . . When Trummy used to play Margie and things like that with the Jimmy Lunceford band his solos were all trombone adaptations of Louis’ trumpet style. Now that he is with Armstrong he plays any kind of style but that: this, for instance, is in his workingman’s “Tricky Sam” style. As a dedication to King Oliver this album strikes me as epic bad programming, for it has little or nothing to do with Oliver—whose work and approach should surely have been reflected in some much more positive manner. If you played this record to someone who’d never heard of Louis Armstrong and then told them that this was the man who practically invented jazz—as indeed he did!—they would be perfectly justified in thinking that you were talking a load of cock.

Somebody Loves Me. Jack Teagarden-Dixieland Sound. Columbia 33SX 1504

I’d buy this one if only for its charm. Diabolical Dixieland with the trumpet player just nowhere, but Jack Teagarden is one of those people with star quality—a very personal quality that mirrors itself in his singing, in his playing: the kind of quality that lifts itself right off the record and into your heart. I have always had the profoundest respect for Teagarden as a musician because within the limits of what he does he is the complete perfectionist. And he never goes outside those limits. Unlike a lot of fine musicians of his period—Coleman Hawkins, for example—he has never attempted to stray outside the particular province which is his alone. He is not a singer like Sinatra, in terms of technique; and he’s not even a jazz singer in the way Louis is. But he has a personal quality which I find very endearing. His trombone playing remains impeccable and the inspiration of many, many musicians. The arguments as to whether Jimmy Harrison inspired Jack Teagarden, or t’other way round, are quite immaterial to me, for Teagarden is a unique individual who has remained, down through the years, entirely himself. Put this record, made quite recently, beside Never Had A Reason, which he recorded back in 1929, and it is still unquestionably the same man—untouched. There are very few people with that quality. Johnny Hodges is one, and I suppose Louis Armstrong is another—though his work has sadly deteriorated in recent years. But they are few and far between.

I like this style of singing because the tunes upon which it is based—as in the case of this one by Charlie Parker—are far better jazz vehicles than the doleful popular songs that most jazz singers elect to work on

Parker’s Mood. Eddie Jefferson. Riverside RLP 41 1

I have always been a sucker for this kind of thing, be it by Annie Ross or King Pleasure. I like this style of singing because the tunes upon which it is based—as in the case of this one by Charlie Parker—are far better jazz vehicles than the doleful popular songs that most jazz singers elect to work on. They are also a better vehicle for the lyrics if the singer has genuine jazz feeling—and this chap Jefferson has a wonderful jazz feel. Another thing. Because there are necessarily so many words to fit the many notes, you’ve got to listen very intently: a good thing in these days, when too many modern jazz records don’t stimulate that sort of attention. By “modern” I mean as of now, and not modern as a school. There is just the possibility that if I heard this too often it might become tedious, but again it might be that when I got to know the words really well and dug their meaning I’d like it even better.

Included is some good work by Junior Mance, one of the best modern jazz pianists in my opinion. I really think that this is an album that would repay more study than is possible on one hearing, and I must be honest . . . I’d rather listen to this kind of thing, which has some jazz meaning, than a lot of those popular songs which try and pass for jazz interpretation but which aren’t at all. The basis of this music is so much better, since the songs are built around what were originally great creative jazz solos.