When film music historians discuss the increasing influence of jazz on movie soundtracks through the 1940s and into the 1950s, they usually mention films like The Best Years Of Our Lives (1946), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Rebel Without A Cause, and The Man With The Golden Arm (both 1955), but they overlook Pete Kelly’s Blues, which was released in the same year as the latter two. This is unfortunate, because it’s a minor classic that deserves close scrutiny.

‘…includes two of the greatest vocalists of the 20th century, Ella Fitzgerald and Peggy Lee, in both acting and singing roles’

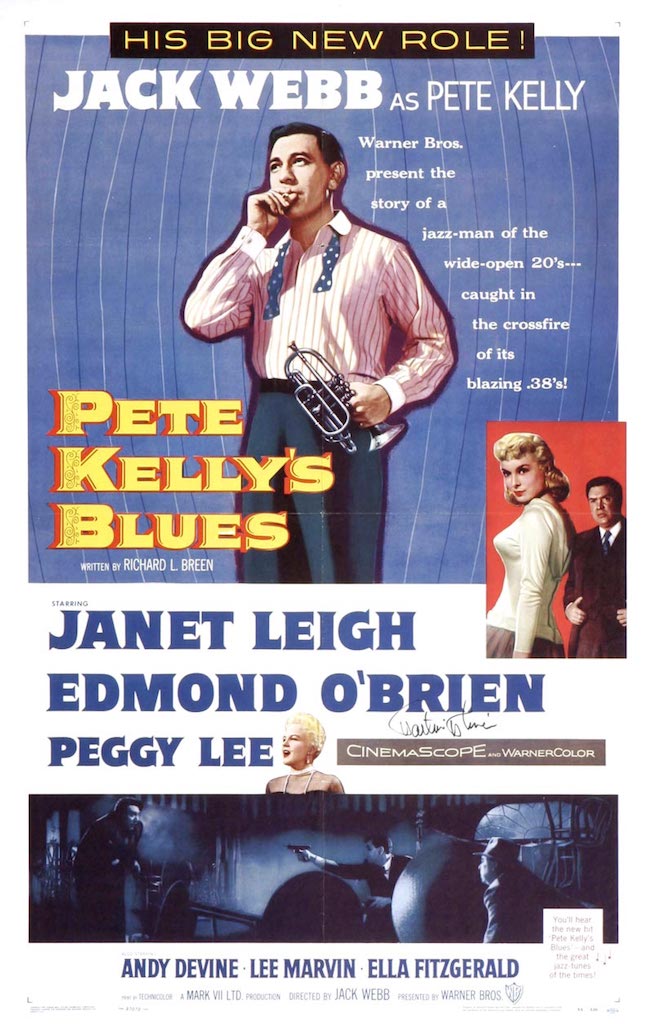

The brainchild of Jack “Dragnet” Webb, Pete Kelly’s Blues is remarkable for the way that it combines elements of a number of genres – period piece, film noir, gangster movie – and ties them all up with an excellent jazz soundtrack, a great orchestral main title theme, and an all-star cast that includes two of the greatest vocalists of the 20th century, Ella Fitzgerald and Peggy Lee, in both acting and singing roles.

Jack Webb was a household name in America when Pete Kelly’s Blues was released. His cop show Dragnet debuted on radio in 1949, and, having moved to TV in 1951, was the second most popular TV show in the USA by 1954 after I Love Lucy. Like Clint Eastwood after him, Webb was able to indulge his love for jazz in his projects when he first appeared as 1920s cornettist Pete Kelly on radio in 1951.

Pete Kelly the movie cleverly sets the scene for the ensuing narrative before the credits roll. As a river boat glides by, we are in New Orleans in 1915 at the funeral of a jazz musician where trumpeter Teddy Buckner plays Oh Didn’t He Ramble. As the funeral cortege moves off, the deceased musician’s cornet falls off his coffin into the mud. Cut to Jersey City in 1919, and the same cornet is changing hands in a poker game. As the camera draws back, the cornet’s purchaser is revealed to be Pete Kelly, still wearing the uniform of a soldier who has returned from the First World War. Cue credits as the main title theme swells dramatically.

The title tune is a lush 16-bar blues that, while being classic film music in itself, is more than slightly reminiscent of Alex North’s theme from A Streetcar Named Desire. Ray Heindorf, boss of the Warner Brothers music department, had conducted the Streetcar soundtrack and composed the Kelly theme, which also appears in a vocal version in the film, sensitively rendered by Ella Fitzgerald. Her album of songs from the film reached number seven in 1955.

As the film proper commences, the camera follows a young woman down a flight of stairs into a speakeasy, the smoky, clandestine world of Pete Kelly’s Big Seven. It’s Kansas City in 1927. In classic noir fashion, we hear Webb’s voiceover. He is still basically Dragnet’s Joe Friday, a tough, moral character, but this time moved back three decades, with a cornet in his hand. Whereas Friday said, “This is the city. I work here. I’m a cop”, Pete Kelly says “If you’re looking for a new way to grow old, this is the place to come, 17 Cherry Street, Kansas City … I play cornet and run the band. We play from 10 till four with a 20-minute pizza break, but the music suits us. There’s one thing about Rudy’s, and that’s trouble. Like one Tuesday night. A lot of people were busy that night”.

‘Webb, unusually for an actor of his era looking as though he’s actually playing his instrument, leads a band that plays some of the coolest, subtlest, most sophisticated Dixieland ever created’

A gangster named Fran McCarg (played by Edmond O’Brien) is bent on extorting commission from Kansas City bands, including Kelly’s Big Seven. This is the basis for the film’s plot. Webb, unusually for an actor of his era looking as though he’s actually playing his instrument, leads a band that plays some of the coolest, subtlest, most sophisticated Dixieland ever created. The real musicians, including trumpeter Dick Cathcart, trombonist Moe Schneider, clarinettist Matty Matlock and tenor player Eddie Miller, were mainly veterans of the Bob Crosby big band and later of the Hollywood studios. Cathcart, ghosting cornet for Webb, has a warm, mellow sound in the style of Bobby Hackett, while Matlock’s clarinet is fluently Benny Goodman-esque. The tight but relaxed rhythm section is driven by stellar big band drummer Nick Fatool. The band’s soundtrack album rose to number two in the charts in 1955.

Pete Kelly is initially intimidated by the gangsters when his hot-headed drummer (played by Martin Milner, later to appear as a guitarist in The Sweet Smell Of Success) is machine-gunned down after taking a bottle to Fran McCarg’s henchman. Kelly’s attitude changes after he witnesses the sadistic treatment that McCarg metes out to his tragic, alcoholic singer girlfriend Rose Hopkins, played by Peggy Lee. Nominated for an Oscar for her role, Lee delivers an exceptional performance while also providing a number of vocals in her inimitable style. After being beaten by McCarg, she falls down a flight of stairs, and, brain-damaged and with the mind of a child, she becomes a resident at Cedardale State Home for the Insane, where she is visited by Kelly. This scene, understated and not in any way mawkish, is genuinely moving, and is one of the dramatic high spots of the film.

Other star members of the cast include Janet Leigh as Kelly’s on-off high society girlfriend, Lee Marvin playing against type as a pacifist clarinet player, and Jayne Mansfield (pre-blonde) as a cigarette girl.

‘…a film that, whether historically accurate or not, involves you in its period detail and makes the music an integral part of the drama in a way that other jazz movies, such as Young Man With A Horn (1950), do not’

As the film moves towards its final scenes, Kelly decides to face up to the mobsters and, in true Philip Marlowe style, dons his trench coat, takes his gun and goes out into the rain-drenched night. A truly eerie and nerve-wracking climax ensues in the deserted, darkened Everglade Ballroom, accompanied by the echoing jangle of a player piano. In the shootout that takes place, one of the mobsters falls to his death, to be suspended for a moment on the glass ball hanging from the ballroom ceiling. The final scene, it has to be admitted, is Hollywood Happy Ending, as Webb, racketeer-free and back in the speakeasy, serenades Janet Leigh. But the overall impression is of a film that, whether historically accurate or not, involves you in its period detail and makes the music an integral part of the drama in a way that other jazz movies, such as Young Man With A Horn (1950), do not.

Jack Webb never made a better film. Pete Kelly’s Blues became a TV series, but the title role was taken by William Reynolds. Webb ended his days as a TV executive, and died in 1982. He should be given due credit for popularising the tough, laconic, basically decent TV or movie hero, usually a cop or a musician, who ploughs his lonely furrow to the accompaniment of a cool jazz soundtrack. Think Lee Marvin as Frank Ballinger in M Squad as Basie swings, John Cassavetes as Johnny Staccato, Peter Gunn and Henry Mancini, all the way up to the more recent LA Confidential.

Pete Kelly has a starring role in that firmament.

Geoff Wills is the author of Zappa and Jazz: Did it really smell funny, Frank? (Matador, 2015)