Younger readers may find this hard to believe, but there was a time when jazz could be heard during general radio programming. Sunday lunchtime meant Two-Way Family Favourites, a show designed to put armed-services personnel in touch with their families back home via record requests. It was not unusual to hear Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, the MJQ and maybe even Miles Davis. At one point, thanks mainly to a couple of his records getting into the pop charts, Dave Brubeck featured fairly regularly. Evidently the public liked him, but many critics could rarely refrain from sniping at him. As a 15-year-old newly-enthused fan I fired off a clumsy but impassioned article “defending” him to JJ. I pray no copies have survived.

Notwithstanding all that critical opprobrium, Brubeck fans have always had big guns on our side. As Clark reports in this book, figures as distinguished as Charles Mingus, Anthony Braxton, Andrew Hill, Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker found much to admire in Brubeck’s work. (Clark elicited some information about the friendship between Parker and Brubeck which I don’t think has been widely known previously.) Eventually new generations of critics began to appreciate the pianist-composer’s contribution to jazz, later albums like London Flat, London Sharp and Indian Summer getting favourable receptions.

Clark’s direct connection with his subject goes back to 1992 when, as a music student, he asked Brubeck to look at a piece he had written. Brubeck was evidently impressed as he suggested they keep in touch. Several articles for various publications followed, prompting Clark to determine on writing a book, a project he has been working on for a long time. He has carried out extensive research, including spending a lot of time with Brubeck during the pianist’s quartet’s tour of the UK in 2003, and subsequently conducting further in-person interviews with Dave, his wife Iola, sons Darius and Chris and others, including bassist Gene Wright. As well as filling in the historical outlines these conversations reveal some charming domestic anecdotes, such as when Joe Benjamin, briefly depping for Wright, won pizza for the Brubeck children in a radio phone-in quiz. There is also some fascinating material about Brubeck’s contact with traditional musicians in the Middle East and India, and how he and drummer Joe Morello were absorbed in the different approaches to rhythm in those cultures.

As most of us scribes know, going to a fountain-head does not necessarily result in getting all the facts pinned down. Artists are like everyone else insofar as their recollections are concerned, and just as likely to drift away from strict accuracy in their memories. Brubeck was reluctant to talk about the Time Out sessions for just that reason. He knew he had forgotten many details and, quite properly, did not want to pass on information that he was not sure of. Whatever, Clark has done a lot of deep research into documentary sources to contextualise, if not always confirm or correct, Brubeck’s reminiscences. As well as having unprecedented access to the Brubeck family archives he has consulted many background sources including press and record company archives, not to mention court records when examining the involvement and influence of mobsters in running clubs, record-labels and, indeed, musicians.

I’ve always been convinced that many people’s antipathy to Brubeck’s music had much to do with a kind of snobbery because of his perceived college-professor image and white middle-class background. This is somewhat ironic since his classic quartet was one of the few mixed-race bands, and Wright was not the first black member of the group. An early edition of the quartet included another black bass player, Wyatt Ruther. Clark describes Brubeck’s reactions to racist incidents and policies in the southern USA at a time when he and other jazz artists were being asked by the State Department to represent the American democratic ideal in the Eastern Bloc and elsewhere. Brubeck’s “jazz opera” The Real Ambassadors, written for Louis Armstrong, deals with this bitter irony. In Ken Burns’ epic documentary series, Jazz, Brubeck was brought to tears by remembering how, when he was a child, his father took him to meet an elderly neighbour who took off his shirt to show that he still bore the scars of slavery, an incident that shaped Brubeck’s humane liberal attitudes for the rest of his life. Over the years he would stand up to concert promoters, theatre managers and TV producers who tried to force him to replace Wright with a white musician.

Clark says he did not want to write a purely chronological account of Brubeck’s life and musical career, but rather to weave these stories into a social and political overview. He has done this effectively, whilst still giving a coherent narrative on the development of the pianist-composer’s art and providing technical (but not too technical) analyses of many of the tracks on record. Occasionally I found this scheme a little disconcerting. It’s not until page 302 and beyond that Clark really gets stuck into biographical details of birth, childhood and family history, as well as certain anecdotes, such as Brubeck’s encounter with Schoenberg, which I’d expected in chapter two when he deals with Brubeck’s studies with Milhaud at around the same time.

Most jazz fans will have some knowledge of the late-50s to early-70s Brubeck-Paul Desmond and Brubeck-Gerry Mulligan recordings and their context, but Clark also provides vivid and detailed descriptions of the pre-classic-quartet era (before Wright and Morello joined) and the decades that followed them in Brubeck’s long and productive life.

If you are a Brubeck fan you will find this book absorbing. If you are still a sceptic you might find that it persuades you to reconsider your view of this very creative musician and very decent human being.

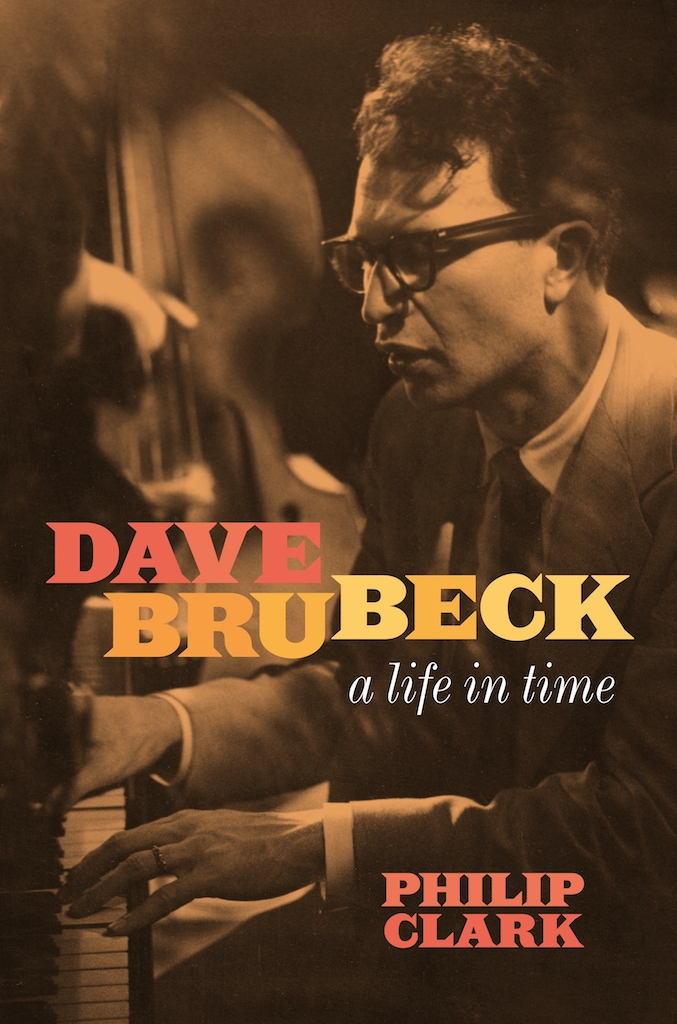

Dave Brubeck: A Life In Time, by Philip Clark, published by Headline-Da Capo, 414 pp including selective discography and bibliography, hb, £25. ISBN 978-0-306-92164-3 (hardback) 978-0-306-92165-0 (e-book)