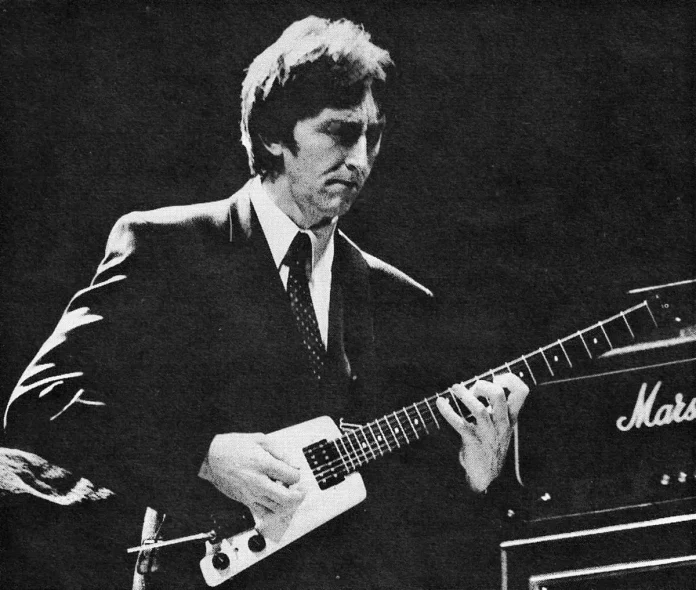

Since he came on to the London scene in the early seventies, Allan Holdsworth has joined the small band of electric guitarists – among them Charlie Christian and Jimi Hendrix – who have radically redefined the character of their instrument and vastly expanded its expressive potential. In a period when the guitar enjoyed unprecedented popularity and produced a correspondingly large number of anonymous exponents, Holdsworth found a way, albeit unconsciously, of leaving an indelible personal stamp on the instrument.

His awe-inspiring facility in all registers is often the first and occasionally the only thing to impress the listener. This is a quite remarkable phenomenon, but there is far more to Holdsworth’s playing than astonishing fluency. He has discovered a new range of expressive nuance in the electric guitar. By combining the sustain produced by overdriven amplification with an extensive ligado or hammer-on technique, carefully controlled finger vibrato and subtle use of the tremelo bar, he has developed an extremely fluid, legato style which is the perfect complement to his lyrical melodic sense; added to that is a richly polytonal harmonic vocabulary.

Holdsworth’s range of influence has been wide. His sound is not only heard among jazz players; it has also filtered through into popular music, and the playing of such guitarists as Eddie Van Halen and Alan Murphy has brought elements of his style to a large if unknowing audience.

In 1990, Holdsworth brought the original and complete item to such audiences when he recorded and played London concerts with the jazz-funk group Level 42.

Holdsworth’s achievements are made all the more notable by the fact that he never really wanted to play the guitar. There’s a logic in this paradox: Holdsworth’s preference for reed and bowed string instruments (the pursuit of the former frustrated by ear problems) has contributed to the distinctive character of his guitar playing. The notion of the jazz guitarist as horn player finds a perfect realisation in Allan Holdsworth.

Not only a reluctant guitarist but also a reluctant guitar hero, Holdsworth is only infrequently impressed by his own playing. At the age of 45, after 20 years as one of the most respected pioneers of the modern electric guitar, he says, with a modesty which bespeaks a high level of aspiration: ‘There’s so much I want to fix in my playing.’

Holdsworth was bom in Bradford on August 6, 1946. He never knew his father, and his mother later remarried. He was adopted by his grandparents and grew up believing they were his mother and father. His grandfather, the pianist Sam Holdsworth, played the role of mentor and teacher admirably well, and the younger Holdsworth attributes much of his individualism to the teaching of the man he calls ‘dad’.

‘He was great. He was a big help in a way. I think he was sort of largely responsible for it coming out a little different, just ’cause he knew where everything was on the guitar, but he had no idea what was normal standard practice for guitar. So I never learnt any of the normal things. Like, I started straightaway with different kinds of voicings of chords. He used to write things out for me to play, show me how to do certain things, scales and chords and stuff, like the way he would have done them on the piano.

‘I did practise scales a lot. One of the things my dad said was: “There’s no point in practising anything in the open position. Don’t play any open strings ever.” So I never did. I never learnt a single scale using any open string. I started out straightaway playing all the scales using only the fingers. Immediately then I could play the scales all over the neck.

‘My dad tried to show me how to read, but I just used to remember the exercises. He’d put something new in front of me and I’d be absolutely useless. The only thing I could ever read was that Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, because it was written enharmonically, with no key signature. But I can’t read; it’s absolutely pathetic. I would learn if I was starting again.’

Early on, Holdsworth developed a taste for complex and colourful harmony, not only from jazz but also the classics. The 1985 book Reaching For The Uncommon Chord, a mixture of biography and musical analysis, was well-named.

‘The thing that always moved me most was hearing a really great chord, or just the way it was voiced. That’s what I live for, that chord. It came mostly from classical music in the beginning. I got interested in certain composers – Bartok, the string quartets, and then The Concerto for Orchestra, and I also liked some of that opera, like The Miraculous Mandarin. Oh, and Debussy and Ravel. I love Ravel’s string quartets. There’s something about that period. Music was just starting to look like scenery; you could see things in the music.’

In pursuit of solo lines, Holdsworth did his share of lifting and dropping the tone arm, but he found the results generally disappointing.

‘My dad had a lot of Charlie Christian records, and I used to learn a lot of his stuff, but it wasn’t long before I realised that when I came to play my own solo, it sounded as bad as it did before I tried to learn what the other guy was doing. I realised I had to go back and find out how I could play over the things. I started taking chord sequences and working out what I could do that would sound good, and not worry about what someone else was doing over it. And I still feel like that. I’m fascinated when I hear what other people do, but that’s as far as it goes, I don’t sit down and try and figure out what it was. I’ll try and do something else of my own and be as elevated as that.’

Holdsworth left school at 15, but not to pursue music. His teenage love, and one that still endures, was cycling. Holdsworth shared the hotel room in which this interview took place with a new touring cycle, custom built for use during his month or so stay in London as a member of Level 42. As a youth he did both road racing and time trials in Yorkshire, and he’s considering entering veteran races in California, his home since the early eighties.

He began to take a serious interest in music in his late teens, while he was working in factories and as a bike repairman. At first he wanted a saxophone, but it was then that Sam Holdsworth suggested a more modestly priced acoustic guitar. There followed lessons with Sam, an electric guitar and experiences with various local groups before an invitation from his friend Glen South led to three years or so in a Top 40 band on the Sunderland Mecca circuit. It was there that Holdsworth was first able to try his hand at the clarinet.

‘I never really wanted to play guitar. I always wanted to play like a horn. The saxophone player in the Glen South band showed me a few things, and I tried the clarinet, but I kept perforating my ear. When I hurt my ears I wanted to try something else, so I got the violin and started noodling on that.’

In recent years, Holdsworth has found an outlet for his horn-playing ambition in the Synthaxe, a guitar-like synthesiser controller with a tube into which the player blows to add expression.

‘The Synthaxe is close to what I want, ’cause it’s a combination of blowing and picking, so it’s like a horn and guitar. You don’t have to blow so hard though, it’s an open blowing, like blowing a balloon up; there’s no embouchure.’

There has been a certain resistance among followers of Holdsworth’s guitar playing to his use of the Synthaxe, but Holdsworth feels they are missing the point.

‘That tends to prove that lot of guitar players are not listening to the notes. They’re listening to something else. It’s the music that counts. Perhaps they can’t relate to the sound of it, but it’s being done just like it would on the guitar.’

It was the sound of Holdsworth’s soaring guitar lines in such seventies jazz-rock bands as Soft Machine, Lifetime, Gong and Bruford and in John Stevens’s improvising group Plough which elevated him to cult status. In those days, unable to play a reed instrument and before the advent of the Synthaxe, Holdsworth sought other ways to bring the non-percussive qualities of a horn to the standard electric guitar. Part of the solution was amplification, which meant the guitar tone could be sustained; another was the development of a legato, hammer-on technique for single lines.

‘I used to play quite normally, like picking normally. Then I found some tapes from maybe 10 years before on which I was using a kind of hammer-on technique, and I thought “That sounded alright, what am I doing this for?” So I just tried to develop that. For a while I thought it was a flawed technique, ’cause I couldn’t do all the things I wanted. But now I actually believe you can play anything using this technique. Since then, I’ve started practising accenting notes other than the ones that were picked. Now I think I can make notes louder with the finger than with the pick. I’ve got to the point where I can silence the picked notes and make other notes louder. So it’s hard to tell which is which.

‘I don’t use any pull-offs, they’re all hammers. Even the lower notes in a descending line. I don’t pull the string off and deflect it sideways to make it ring; the finger below goes down, so it’s basically all hammers.’

The use of light strings was another important element in simulating a horn sound. It both enabled fast technique and facilitated hammering on and such expressive devices as vibrato and pitch bending.

‘I’ve always used light strings, because I’ve always felt there was a direct correlation between how hard you hit the string, naturally, and the gauge of string that you use. I strike the string very lightly. When other people play my guitar they put it out of tune: just by holding a chord down it’ll be all out of tune. When I first started using light strings they were hard to get. If I wanted a .008 top string I had to use like a Cathedral octave banjo string, and then displace the other strings by one and throw out the sixth. I’ve drifted between .008 and .010 gauge sets. I used .010s for a while because I liked the way they sounded on chords. But I liked the way .008s sounded for solos; they had more of a ping. So I finished up most of the time I was using a wood guitar using a .009, but since I’ve got the plastic Steinberger guitars, they work just great with .008s.

‘I’m really over the moon with these Steinberger guitars. The necks are specially made for me. They’re made with no relief, ’cause I’ve never believed in that. I don’t believe in that theory at all. It doesn’t make sense. I know why they did it on old acoustic guitars with a big action, just because the string where it vibrates the most in the middle is more likely to buzz. But it causes problems all over the guitar. The best way to me is to take two straight lines; so the neck’s made with no relief, and it’s got a 20in radius, so it’s really flat, and Jim Dunlop 6000 frets, so they’re really high. There’s something about the guitar when the neck’s got an underbow in it, it feels soggy in the middle.’

Holdsworth felt that his light, legato touch created certain problems in Level 42, where he was expected to be a rhythm as well as lead player.

‘I didn’t really want to play the guitar as a percussive instrument, and strumming has never been something that appealed to me at all. It’s not something that I’d ever use in my own music, but it’s quite a prominent thing in Level 42, so it’s been strange because it’s such an alien thing for me. It doesn’t sound right to me, but they’re probably being polite and telling me it’s fine. I just don’t see the guitar in that role.’

Holdsworth’s favoured role for the guitar – as a source of melody and harmony rather than percussive rhythm – is also reflected in the vocabulary he draws on in his improvisations. Allied to his love of rich harmony is a passion for the polytonal style espoused by such hornmen as John Coltrane, and, more latterly, Michael Brecker. He’s careful to point out that his approach to building guitar lines is polytonal rather than simply chromatic.

‘I don’t play chromatically at all, no, because I try not to. Steve Hunt, our keyboard player, always calls that “dusting” ’cause it’s just like cleaning the keys, sweeping your hand over the keys. If something chromatic comes out of my playing, it’s usually because of another motion, or an internal motion. Like say playing up a bunch of triads starting on G then going down by semitones through F# and F. If you’re thinking about using other scales to get from one place to another, or superimposing triads on top of other things, then there’s bound to be notes that are next to each other somewhere. Maybe people hear that as chromatic, but I try really hard to avoid that.

‘That’s one of the nice things about playing over one chord. We usually do Devil Take The Hindmost because most of the other tunes I write have a lot of chords. Sometimes it’s really hard; sometimes I can’t play anything on it. Sometimes it’s just like I wish I hadn’t played it. And other times you just start coming up with ideas on it. It’s like a place to experiment.

‘Sometimes I’ll just play off the different triads. Other times I’ll use like two together, like two sets of triads joined together. Like a D minor and an Eb major or something. The whole step-half step scale is interesting too, because although it has a kind of horrible sound most of the time, especially the way most people play it, it’s an unbelievable vehicle if you start jumping things around on it. It’s almost so that people wouldn’t recognise what it was. I mean the way it sounds if you take different intervals. It’s quite a fascinating thing, that.

‘I’ve been trying harder and harder not to play that in scale fashion. I still do it, through habit, but what I’d like to do is make everything I play sound inside out and upside down. I concentrate sometimes when I’m practising on not playing more than two notes going in the same direction, but it really gets hard. And when panic sets in, which it often does … I wish I could break that panic thing, where you concentrate on doing something rather than nothing, when it really should be the other way. Sometimes we play at soundchecks and I think “I wish I could have done that on the gig”. Or I’ll have that feeling, but as soon as I get to the gig, my hands are shaking. It’s hard to make music like that. Nerves play a big part for me, and it’s a problem.

‘Some guys are really good at balancing it. Out of all the players I’ve heard over the last few years, I really like Scott Henderson. He particularly has that thing of just being able to hang about until something happens, whereas I tend to push it. And I’ll push and nothing’ll happen, and it’ll just be like a joke; it won’t be what I wanted, it won’t be anything. It won’t be any good to anybody else and it wasn’t any good to me. I’m really trying to get to that point now, where I’ll be improvising, but not pushing it.

‘People have said to me “Scott Henderson sometimes sounds like you”, but he doesn’t, not at all, to me. It might be there as a coincidence, but I don’t hear it. And he’s got so much of himself in it that he’s beyond that anyway. It’s like Michael Brecker and John Coltrane. You know, you can hear similarities but Brecker’s elevated himself, his playing is so incredible that it’s his. It’s great. Actually, he was gonna play on one of the albums, but we just couldn’t schedule it. But I’d love to get him to play on something.

‘Henderson’s coming much more from a bebop sort of standpoint than me, and he sounds like he’s really improvising. You never know what he’s going to do. Scott seems to make it come out in a fresh way. It’s almost like when I hear Keith Jarrett. When I hear Keith Jarrett play a standard, I never hear any standard things. It’s obvious that he’s completely familiar with all of that stuff, but he actually sounds like he’s improvising. That’s absolutely wonderful to me.

‘A lot of jazz musicians tend to play more from things they’ve done before or heard before, but it doesn’t sound like that when you’re really improvising. I don’t think it should be like that. It’s a true understanding of the music rather than a formula. I think a lot of guys play off some sort of a formula. So when they see this chord they know they can do that, as opposed to seeing it as a separate entity which can be what they want to make it right then.

‘That’s the way I’ve always felt about the guys in the band, or the guys I’ve played with, like Gary (Husband) and Jimmy (Johnson) and Steve Hunt. They’re all such great musicians, and as far as I’m concerned they’re right up there with the best guys in the world. The music is mostly improvised, and we play over reasonably complicated chord sequences. And I still think that in essence it’s kinda jazz, even though we came up from different things.

‘But we have problems with radio stations, ’cause straightahead programmes won’t play anything of ours. They’ll say well, it’s not jazz, it’s rock. Then the rock station says that’s not rock, it’s jazz. So instead of getting a little of both we get neither.

‘Because I’ve been doing it for a long time, I realise that the music I play can’t be taken any further in terms of audience. We’ll never get any more people than we’ve got already, so I have to be prepared to do this continuously, knowing that nothing can improve really. We’re at the mercy of the record company and the radio station. But in a way it doesn’t matter whether there’s a new album out ’cause people come and see the guys play; they just want to see people play, which is great.’

Allan Holdsworth visits Britain this month. See Jazz News.

Selected discography:

Soft Machine: Bundles (1975)

Bill Bruford: Feels Good To Me (1977)

John Stevens: Touching On (1978)

Allan Holdsworth/Gordon Beck: The Things You See (1980)

Allan Holdsworth: Metal Fatigue (1985)

Allan Holdsworth: Secrets (1989)

Chad Wackerman: Forty Reasons (1991)