His is not perhaps the name that first comes to mind when thinking of the swing era, but Chick Webb’s remarkable legacy lives on. In her absorbing and thoroughly researched biography, Stephanie Stein Crease explains and assesses his importance and influence not only on drummers in jazz, but also on the music itself and, perhaps most lasting of all, on his role in the life and career of Ella Fitzgerald.

As Crease traces his far from affluent childhood in Baltimore, it is quickly apparent that Webb was special. He was beset by health problems affecting his growth and stature and overcame them in a display of physical fortitude matched by quite remarkable inner strength. He taught himself to play drums and he and a small group of like-minded friends eventually moved to New York where he began a struggle for recognition.

Through newspaper accounts and interviews, Crease explores how, in the matter of racial issues, New York differed little from Baltimore. Discrimination and prejudice affected opportunities, and even though Webb’s exceptional qualities were recognised there was separation of black and white. Not only were musicians kept apart, so too were audiences, with venues separating black and white dancers into roped-off areas. The colour divide also created difficulties with management and promoters, although Webb was fortunate in attracting the attention of Helen Oakley, whose important role is detailed here.

As becomes clear from sources consulted by Crease, another of Webb’s inner strengths was his determination to reach the top, which meant playing at the Savoy. There, he participated in the widely publicised Battle of the Bands, winning against opponents such as Benny Goodman and Count Basie, and eventually became the undisputed King of the Savoy.

Although the Savoy meant steady work in one place, during the late 1920s and early 1930s Webb undertook often arduous tours of one-night stands and these undoubtedly exacerbated his lifelong health problems. There are instances of engagements where another drummer played the bulk of the session with Webb coming on only toward the evening’s end, when he had to be carried onto and off the bandstand, but Crease’s research finds no indication that he ever complained.

Often playing in New York during the second half of the 1930s, Webb and the band were more settled and it was now that he made the best of his recordings. This was also the time when he was to make his lasting mark on the history of jazz. Although he had already influenced jazz drummers, especially contemporaries such as Kaiser Marshall, Jesse Price, Bill Beason and especially Gene Krupa, his chief legacy was a singer: Ella Fitzgerald.

Much has been written of Fitzgerald’s discovery and development, some of it speculative, some guesswork, and Crease’s recounting sets the record straight. What also become apparent from her sources is that there were striking similarities between the drummer and the singer. Both were self-taught yet brilliant musicians, both possessed steely determination gearing them toward success, both demanded the best from those who worked with them, and both cloaked their toughness beneath genuinely amiable exteriors.

Among the reasons for these successes was another of Webb’s qualities: his absolute commitment. There was also his steadfast determination to seek perfection in his own playing and he expected nothing less from the other musicians in his band. Not that he was a harsh taskmaster; as Crease’s sources state, he was an inherently kindly man and this encouraged others to always try to measure up to his expectations. Constantly alert for sometimes as yet undiscovered qualities, he brought into the light many newcomers, both instrumentalists and arrangers. Among them were Louis Jordan, Edgar Sampson and Mario Bauza, who owed much to Webb. Interviewed for Jazz Journal by Stan Woolley in 1989, Bauza recalled how he was told by Webb to attend a rehearsal. “Well, when I arrived there was nobody else there but Chick, who said the rehearsal was just for me. He told me I was the man he was looking for but didn’t like the way I phrased, it was too Latin. So he hummed the way he wanted each number to go and I played right along with him on trumpet. We did this for two or three nights until Chick was happy with what I was doing. You know, although he couldn’t read a note of music he had a real musician’s mind.”

Ella Fitzgerald, too, had a musician’s mind and this, together with her determination, are examined by Crease as she discusses the final four years of Webb’s life. Financial success was brought by records featuring Fitzgerald: Sing Me A Swing Song, Oh, Yes, Take Another Guess, The Dipsy Doodle, If Dreams Come True and most successful of all, and a highly unlikely hit song for a swing-era band, A-Tisket, A-Tasket. That the singer pulled it off shows that Mario Bauza was right when he said “That woman was sensational.”

Another of Webb’s qualities made clear here is that he never complained about his health, was always cheerful, eager to perform, never gave anything less than his all. A result of this was that even though he had periodically spent time undergoing hospital treatment for the spinal tuberculosis that had plagued (and pained) him throughout his life, none of his musical associates and friends appear to have been prepared for his death in 1939 when he was only 34 years of age.

This biography of Chick Webb is not only an excellent account of the life of one of the finest jazz musicians, it is also a tale of extraordinary courage in the face of physical disability and racial discrimination.

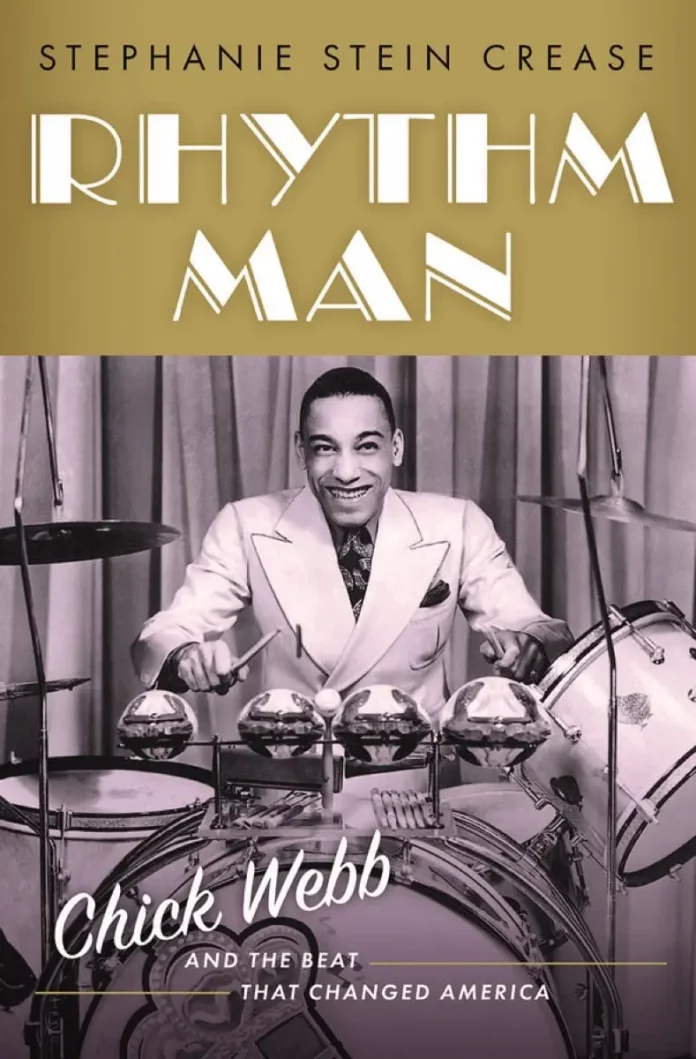

Rhythm Man: Chick Webb And The Beat That Changed America, by Stephanie Stein Crease. Oxford University Press; hb, 360pp; 29 photographs; bibliography; discography; indexed. £27.00 / $35.00, ISBN: 9780190055691. (Ebook £23.00 / $18.00, ISBN: 9780190055714.)