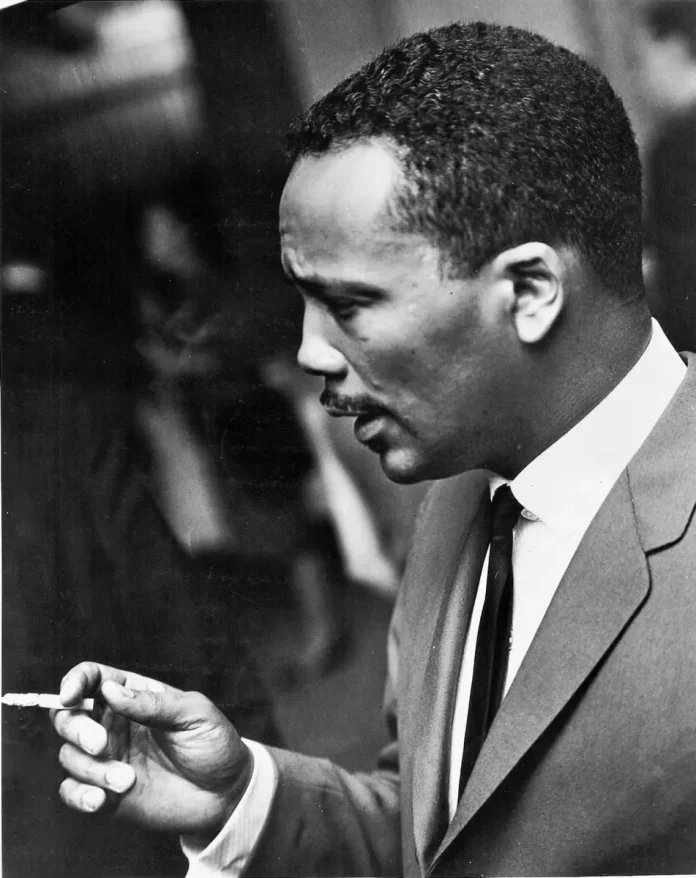

This is one of a series of taped interviews with musicians who are asked to give a snap opinion on a set of records played to them. Although no previous information is given as to what they are going to hear, they are, during the actual playing, handed the appropriate record sleeve. Thus in no way is their judgment influenced by being unaware of what they are hearing. As far as possible the records played to them are currently available items procurable from any record shop. This in some respects differs slightly from the usual standard In My Opinion. It was taped at a dinner table at which my honoured guests included that outstanding arranger and musician, Quincy Jones, and the Hon. Gerald Lascelles who cued many of the questions to which Quincy provided the answers. Whilst the music does bear close relationship to the text it was in this case used more as a background than the main focal point of the interview. – Sinclair Traill

***

Blues And Sentimental. String Along With Basie. Columbia 33SX 1332

Do you know Harry Lekofsky? He has been my concert master for years. When we did the Milton Berle show with Lionel Hampton, Harry was forty years old, and he said, “Man, for thirty years I’ve been playing violin, I’ve played with everybody and I’ve played nearly everything there is to play – now, man I want to play some jazz!”

And I thought that was kind of funny and I looked at him and said, “Well, man that’s a bad kind of axe you’ve got there to play bebop on, it’s not right.” But he would try and make it, and so we’d sit for hours there at A.B.C. and he would play something like I told him, over and over again. But it always sounded corny, like dotted eighth notes and sixteenths. And I would say, “No, Harry try again, like this.” And we’d write it down, so he’d change the bowing, until it looked like morse code or something. But he tried and tried until he got it, so really it’s just a matter of indoctrination.

And he proves he finally got it with those things he did with Bags, like Swinging ‘Til The Girls Come Home or Stringsville. The things he did with strings! It proves to me that when I am ready, and that’s not yet, that what I want to do is to take some strings and really make them sound funky. It can be done, Harry and I proved it. We found a way to notate a thing so that we were sure it was in notation with bowing that’s right. On ‘String Along With Basie’ – Blues Bittersweet – we wrote that out straight to start with like the horns would play it, then for the strings, and really there is no relation between the two, yet it’s on the paper and it sounds right – the guys didn’t know what they were playing yet it sounds good. It was down on the paper and they just kept sawing away the way it was written for them. I don’t mean to say that you can experiment with people on record dates all the time, but I mean we did have at least eight bars in there, which proves if you write or notate correctly, it will come out good, whoever plays it.

B.D.B. Ellington-Basie Battle Royal. Philips SBBL 657

Basie as a pianist? Well, you don’t talk about him academically, for Basie’s got nothing to do with being academic – he’s so real man, it scares me, I don’t believe it. I adore him and love his playing. Did you ever hear the Basie band at rehearsal without Basie? If you did you would realise what a disciplinarian he is. The band sound completely different with him and without him – you have no idea.

Of course, the difference between his music and Duke’s is that Duke’s can’t be shared by anybody except the listeners, because it can’t be re-created by anyone except Duke. Basie’s sound is different, a different kind of effort. Duke’s sound is made of half-bells, of personalities, and Duke’s mind – only Duke’s mind and Strayhorn’s and nobody, just nobody, can touch them for it’s masterminded by Duke.

But you see Basie’s thing is an institution, the very basic essence of swing. And that’s why people like to imitate him, they can get closer to that kind of music – but they can’t ever copy Duke.

Chopin’s Prelude No. 7. Jimmie Lunceford. Philips BBL 7037

Well, that was another wonderful band. I used to listen to them on stage and I used to talk to Joe Thomas (they used to call him ‘ole gal’) and he used to tell me how Lunceford was different; he was so exact. Everything he did, everything he wore had to be exact, from his tie to his shoes, it all had to be just right. And the same with his band on the stage, they had to be exact and just right.

It was an incredible band in its polish and musicianship – they should be here today, up there with Duke and Basie. And if they were I think this would be the greatest era that jazz music has ever known – in fact it probably is anyway. You think that you can sit, as I did the last time I was at Monterey, and Louis comes on and plays and then Little Jazz – he plays, then Dizzy takes over – and then Miles. And we had them all on one night, the whole history of the jazz trumpet! It was like listening to Bach, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Ravel and Bartok all together. From Louis to Miles in one night, man, it will never happen again. So I wouldn’t trade this era for any time ever.

‘There were always about 4 or 5 piano players there and some of them would put hats over their hands so that the other cats couldn’t see what they were playing’

Speckled Red. The Dirty Dozen. Coral LVA 9069

I used to hear a lot of that kind of music when I was a kid in Chicago. It was before I was really interested in music, I used to watch those cats, and you know some of them would play with hats over their fingers. At house rent parties, those whisky drinkers, those serious drinkers, the professional whisky men; those cats were funny. They’d play the strides and they looked big. I don’t know if they were as long and lanky as I imagined because I was small at the time – only about 8 years old, but I used to look up at them and they had a beer here, a scotch here, and always a plate of chittlings at the back. There were always about 4 or 5 piano players there and some of them would as I said put hats over their hands so that the other cats couldn’t see what they were playing. They seemed to forget the other guy could hear what they were playing, they didn’t want him to see where the notes fell. There was a tremendous conceit amongst those old piano players – it was always a fight as to who could come off best. It was funny how they were all afraid of those blind cats – if Tatum came in they would all stop playing. And who can blame them at that!

Da Capo. Modern Jazz Quartet. London LTZ-K 15207

Well, you can take a basic theory and try and be profound with it, but before you do you should find out what the plan has to be. Like a doctor trying to perform brain surgery before he knows if he can give penicillin – find out how to give the anaesthetic first.

You see, Bach closed the door on fugue and counterpoint. He did it so well that nobody has been able to touch it, so when you talk about fugue and counterpoint, then Bach is the boss. He laid it down so good that although many people have tried to emulate him, he just can’t be touched. Many people have tried various variations on it but Bach closed the door on it. So if you say, “I am going to try and start at the very beginning, I know this line goes this way and it has its own harmonic content within the melody, but I think I’ll try another one” – well, you’re just kidding yourself, for Bach had already figured it out, so why go back through that again. One has to accept what he did and try and understand it thoroughly, so if one can’t surpass it, and no one can, then at least one can understand what he did. There are, after all, only twelve notes, so why try to go back and recreate the whole theory. Just stay with what you know.

Duke does his own thing, he’s very much influenced by Ottorino Respighi, but he only uses what he hears for his own purposes, which is the way it should be done. Like the famous Patek Philippe watch company who in their watches take the best parts from all the watch manufacturers in Switzerland to put in their watches – so should we when writing music. The best components only. We have all these fine things to play with, you know – something from Lester Young, Chu Berry, Louis and through to Palestrina – all these good things to pick from.

‘…harmonically we haven’t caught up with the guys who were writing music a hundred years ago. Jazz has contributed nothing to music harmonically – the only thing it has of its own is spirit, and approach’

But harmonically we haven’t caught up with the guys who were writing music a hundred years ago. Jazz has contributed nothing to music harmonically – the only thing it has of its own is spirit, and approach. Everything else is borrowed. Charlie Parker proved that, you know. But jazz is real!

I don’t think this fusion of the classics and jazz will ever come about, one will borrow from the other, but there will never be a complete fusion. The masters were real craftsmen, think what Ravel must have gone through to get that ‘Daybreak’ effect – thousands of notes, just to paint the picture. It’s really beautiful and it’s music, music with a capital M.

And in Duke’s compositions the same thing happens often enough, he goes to endless trouble. He uses the personalities of Hodges, Carney and Ray Nance and mixes them all to get the colours he wants. Duke, he can take the worst musicians in the world and make it come off because he uses a guy for his essence. He takes the essence of a person and is able to project it onto the musical picture as he thinks fit. He is a real painter, a producer of music. And yet at other times he is as seemingly careless as it is possible to be. I remember at Newport, one year, the time Gonsalves did that hundred choruses of Diminuendo, Duke and the band were due to play a thing called ‘The Newport Suite’. Well, I swear that five minutes before they went on stage, Duke hadn’t the slightest idea what they were going to play – nobody had done anything about anything. Yet, on they go and Duke takes command, a little of that Hamilton clarinet, some Carney baritone, a little from this personality, a little from that, and bang, out comes the Newport Suite!

I Left My Sins Behind. Alex Bradford – One Step. Stateside SL 10047

American music has got to come out of the soil. Looking at it from an orchestrator’s standpoint, we have got to develop the language. Jazz is in some ways crude and in other ways polished and we have got to capture all its facets. We need the craftsmanship of the classics together with the feeling that a Muddy Waters or a Ray Charles puts into his work – when you get those polyrhythmic things happening like it happens with the best gospel groups where they get those things really moving. An orchestrator has to feel it and to be able to conceive what the essence of the music really is without losing the spirit of the thing. A kind of blending of soul and science. The technique, the colour and other things an orchestrator uses, plus the true feeling for the music, the true sound of jazz, that’s what I am aiming for.

‘…the Africans didn’t know anything about melodic form, yet what they brought and what the Creoles already had, it all went into the jazz mixture’

The Pearls. Jelly Roll Morton. H.M.V. DLP 1071

That Jelly Roll Morton, he was a thinking man you know. Did you ever listen to the Library of Congress records he made? In there he talks about how the Africans came to New Orleans with this strong rhythmic concept, and met the Creoles who had fine educations having been raised by the whites and everything, and some even had conservatory backgrounds. But the Africans didn’t know anything about melodic form, yet what they brought and what the Creoles already had, it all went into the jazz mixture.

I may be wrong, but I think the British and the coloured Americans have the biggest rapport in some respects, for you see they took the spirituals which in most cases are just a mixture of English hymns and folklore mixed with this feel concept.

The Africans didn’t know anything about 4 bar or 8 bar structures, so when they were exposed to them they just recreated what they knew on the 4 or 8 bar structure, but the basic form was still there. It’s like Lloyd Price singing Personalities, the old English folk song – he nastied it up and it comes out like a 12 bar blues thing. So as Jelly Roll says, all that early jazz came out of a bunch of things – and it is important that we keep all those things, for to me that fusion is still important if one is to get that kaleidoscopic effect, which to an orchestrator is very important. Jelly Roll got it on some of those records of his.

‘…the audience want to relate to something they can feel and understand, and not sit there and just admire another man’s musical prowess. That Ornette Coleman music, it’s embalmed already’

Cherry Red. Joe Turner – Boss of the Blues. London LTZ-K 15053

The blues are becoming more and more popular back home. You told me about the enthusiasm for that Blues Package you and Gerald heard just recently – it’s happening back home as well. A kind of return to the soil, a rejection of some of the avant-garde stuff, that out, progressive jazz, much of which is nothing more than musical masturbation. This new feeling for blues, I have seen it happening all over the world. I think it’s a kind of feeling of wanting to participate – the audience want to relate to something they can feel and understand, and not sit there and just admire another man’s musical prowess. That Ornette Coleman music, it’s embalmed already.

You can call it soul music or what you wish, but there is this tremendous feel for it everywhere from Tokyo to Hawaii. Even in France, where they have always been pretty cool, they no longer want to sit and just listen to someone who, although he may have brilliant ideas, does not let them participate in their music – they want something which relates to their own personal experiences.

3x3x2x2x2 = 72. Stan Kenton – Adventures In Time. Capitol ST 1844

We said that the soul is coming back into music and I think it’s a good sign, because to me it shows that people are feeling the music more. You know I hate to say this, but I felt that if this progressive stuff was tied up in people’s emotions I would honestly be scared for the world. If people left the blues for this, it would frighten me. Stravinsky, he said, didn’t he, “The only way to have freedom is to have restriction.” Keep in that square baby, and we’re all together!