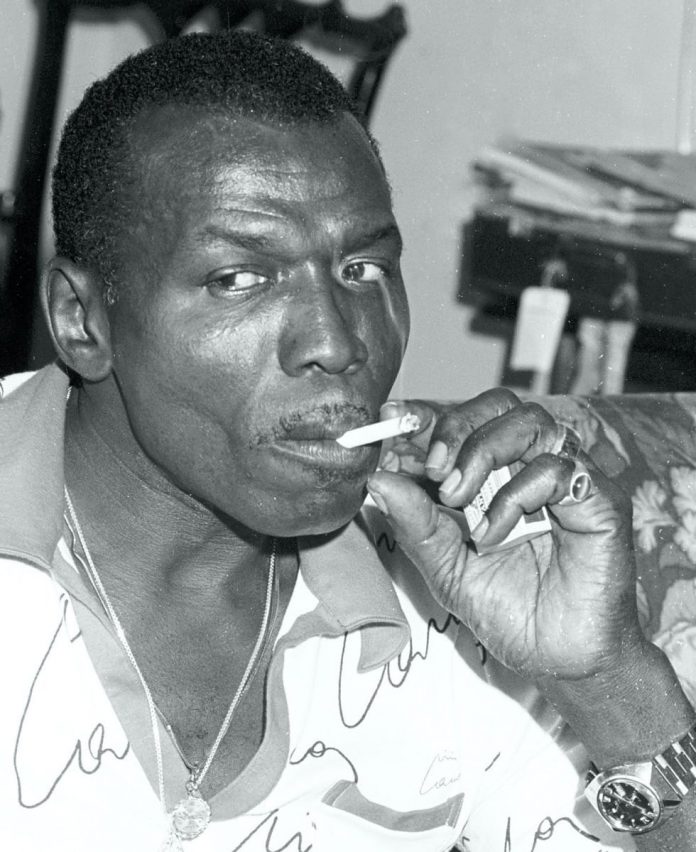

In addition to being widely acknowledged as the greatest drummer in jazz today, Elvin Jones is a very easy man to interview. As I hope the following transcription will show, his is a mature personality of high integrity, and he has strongly held views about jazz. In the interview, I tried to avoid covering ground already dealt with in other interviews. I talked with him during his recent season at Ronnie Scott’s.

The first record I remember you on was the one by Tommy Flanagan.

That was on the European tour we did with J. J. Johnson in 1957. We really had a ball with that band! Besides J. J. and Tommy and myself, Bobby Jaspar was on tenor and Wilbur Little on bass. About the record though, I don’t think they knew what hit them. When we went into the studio, the first thing we did was to send out for two quarts of gin and a case of beer. You should have seen the place by the time we did the last take!

What was your first recording date?

I remember I was very nervous. When I was in Detroit, Dave Usher who was associated with Dizzy when he had his own label (Dee Gee), wanted to record Wynton Kelly. The records didn’t turn out too well, as Wynton was playing a lot of strange things and we couldn’t seem to get together rhythmically. [As far as I can trace this session remains unissued – M.S.]

You have played on one or two unusual recording dates over the years. I’m thinking particularly of the one with Lee Konitz for Verve [Motion] and with Earl Hines for Focus. How did the one with Konitz come about?

I didn’t know Lee Konitz very well, I’d only met him a couple of times before, but when he called me up I was very pleased to do the record. I didn’t know it at the time but I found out later that he originally tried to get Max Roach, but Max wanted too much money.

There is one man who is really my hero – Kenny Clarke. Kenny has everything these other drummers have and something more besides. I don’t know quite how to put it in words, but he brings out the human element in his drumming—his warmth as a person comes through

I tried to give Lee a suitable backing, and of course we had to overcome the problem of dynamics. Things can go wrong so easily when there’s just one horn with rhythm. I relied a lot on Sonny Dallas – by the way, he’s a tremendous bass player, you know – to get the beat together. Anyway, I think the whole thing worked out well.

And the album with Earl Hines?

Stanley Dance had a lot to do with that. He wrote the liner notes for the album and organised the date. I didn’t know quite what to expect, as I’d never heard Earl Hines before. Anyway, we managed to fit together alright, and I enjoyed very much working with him.

That record is rather difficult to get hold of. It was never issued over here and I don’t think it’s even listed in the Schwann catalogue.

That sort of thing is a problem which could be got around quite easily and I’m sure would make a lot of difference to the sales of jazz records. For instance, we were in Minneapolis recently, and I went into the biggest record store and found they didn’t have any of my records in the racks. Any number of pop albums, of course, records by groups you never even heard of. The manager said this was because they couldn’t get my records from the distributors, so I called Blue Note in New York and asked them what was happening. Anyway, you can now buy my albums in Minneapolis!

The other thing that is now happening for me, but only after I made a big noise about it, is proper promotion. You can’t expect anyone to go and buy my records just on the strength of my personality! They must have a chance to hear them. And most of the disc jockeys wouldn’t play jazz.

There are many outlets for jazz which are not being exploited. You know, every supermarket has racks of records. There’s always plenty of Frank Sinatra albums, but not much jazz. Perhaps the big men in the record companies will have to come to an agreement with the supermarkets. Maybe they’d have to charge less but I’m sure they’d sell a whole lot more jazz albums.

Do you ever find there is a difference between what a recording sounds like, or on the playback, and what the actual record sounds like?

There was one company I was under contract to, I made two albums for them, but they didn’t pick up the option. I don’t know what it was – maybe they just didn’t like drummers – but on one of them the recording sounded fine in the studio, and the actual album was so terrible I couldn’t believe it was the same thing at all.

The best studio I think is Rudy Van Gelder’s. There are other good ones, of course – Columbia has one in a converted church that has fantastic acoustics. I have acetates or test pressings of recordings Rudy has done, and I have the actual records, and if you play them one after another you can’t tell any difference at all.

How do you feel about pop-jazz?

I think the jazz musicians who are involved in it are sacrificing their artistic integrity in order to reach a wider public, and I don’t think it’s necessary. Jazz needs all the talent it can get right now, and these musicians are just wasting themselves completely. I would never compromise in this way just to make more money.

I believe Wes Montgomery was very unhappy about the situation he found himself in.

Wes was a good friend of mine. He once came into a club where we were playing and I asked him to sit in, but he didn’t have his guitar with him. I was kidding him about all the money he must be making, and a very sad troubled look came over his face. He didn’t raise the subject again, and I didn’t mention it either. When he had that hit record, the men in the record company came and said to him: ‘Now we are going to direct your career’. I think he just drove too hard, and having a weak heart, the frustrations and pressures just killed him.

What about Miles?

Well, Miles is really the ringleader in this whole thing, you know. His records like Bitches Brew and In A Silent Way are beautiful, very cleverly done with special effects – and the scissors – somebody must’ve had a sore thumb from all that, but he can’t reproduce the sound in a club or concert.

You recently made your debut as a film actor, I believe.

The movie’s called Zacharia. It’s a Western, and I play the part of a gunslinger and also do a ten-minute drum solo. It was made in Mexico, and its due to be released in the States in 1971. I really had a ball doing that.

I’d played in films before – on the sound- track. I was in the band for Quincy Jones’ The Pawnbroker. We also did a film sound track with the trio, for a small film company. They must have messed it up somehow, though, because when Joe Farrell saw the film he said the soundtrack was quite different. It was called The Long Stripe – what you’d call a blue movie! We recorded about fifty minutes of music for it.

Which drummers do you admire?

Dave Tough impressed me a lot, and Sid Catlett. Chick Webb I’ve only heard on records. Max Roach I admire very much as the great technician, and Roy Haynes is very fast. And you mustn’t forget Philly Joe. But there is one man who is really my hero – Kenny Clarke. Kenny has everything these other drummers have and something more besides. I don’t know quite how to put it in words, but he brings out the human element in his drumming – his warmth as a person comes through. He is the perfect accompanist, too, he knows exactly when to bring it up and take it down.

Have you heard the Clarke-Boland band?

Not in person, only on records, the two they made at Ronnie Scott’s. With those musicians they’ve got, the band can’t be bad! I don’t really think they need another drummer, though, with Kenny Clarke around. A second drummer could just foul things up. I’m surprised that Francy Boland does most of the arrangements, because Johnny Griffin is a fine writer and Benny Bailey, too, he did several arrangements when he was with Lionel Hampton. In my brother’s band [the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra] they use arrangements by anyone who can come up to their standard.

Are there any groups which have particularly impressed you recently?

Freddie Hubbard has a beautiful band. I think its about the best one around, after mine! He really should be playing all the festivals and things, getting more exposure. Lee Morgan has a very good group, too.

Have you ever considered settling in Europe?

I love coming to Europe because the audiences treat you with such respect, but I wouldn’t want to move permanently. Some of the musicians who came over and stayed have done so because the pressures on them were too great. I would rather try to face these problems than run away. Other musicians, I think, have come over because they felt that they were getting nowhere, musically I mean, in the States, in addition to the other pressures on them.

What about Kenny Clarke?

Kenny first came over with the U.S. Army and met some French people in the place where he now lives just outside Paris, and became very close friends. He speaks fluent French, too, which helps. Kenny has been running back and forth between Europe and the States for years.

I remember hearing the group he had with Bud Powell and Pierre Michelot, the Three Bosses they were called, at the Blue Note in Paris about ten years ago.

Yes, did you know I once replaced Kenny Clarke in that group? He was taking a vacation for two weeks and asked me to play with them. That was something else!

How did you come to form the quartet?

Joe Farrell was with the trio for over three years from late 1966 to early this year [1970]. We had a ball for three years, made a couple of records that were very well received [Puttin’ It Together, Blue Note BST 84282, and The Ultimate, Blue Note BST 84305] and I was very sorry to see Joe go because he really is one of the great ones. But it was his choice. One day he phoned and said he wouldn’t be able to make it that night, so I called George Coleman. Luckily he was free and after one or two other dates I asked him to join permanently. I am very happy to have Wilbur Little on bass, because he really knocks me out. He was in the trio before Jimmy Garrison, you know, for a short while. On the same day that I phoned George Coleman, Frank Foster called up. I’d known him a long time (he was on my first album for Riverside) and knew how many disappointments he’d had through being let down and misled by impresarios – Frank’s not a very aggressive character, you know. I wanted him in the band, too, but he had a number of commitments to meet before he could join. I didn’t have too much work at the time, so that was alright. The quartet’s been together now for eighteen months.

Apart from the obvious differences of having two horns instead of one, how do you see the quartet as being different from the trio?

Not really all that different. My aims are still the same – to do our best to play good music, without compromising our integrity. And to create the right working atmosphere in which the group can develop and make progress.

What will you be doing next?

We’re doing some concerts in Germany after we leave Ronnie Scott’s and then we’re going back to the States, to the Village Vanguard and some other club dates. In between there is the thing with Ginger Baker. He has challenged me to play with him and we’re trying to arrange it.

Early next year [1971] the first album by the quartet will be coming out on Blue Note. We recorded it on July 17, and it’s called Coalition.

Next summer we’re hoping to do a two-month season with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. We’re working to a deadline of June. The orchestra has been in financial trouble and we hope to be able to help out, by bringing people in to the concerts who wouldn’t normally go to them. Also I think it will help us by getting us exposed to an audience that doesn’t normally listen to jazz.

Will you actually be playing with the symphony orchestra?

Yes. Frank Foster is working on the arrangements now. We are trying to achieve a complete fusion between the quartet and the orchestra. I know this type of thing has been tried before, but I don’t think the results have been too successful so far. I would very much like if someone from Jazz Journal could be present to experience the music and record his impressions.

I think it should make very interesting listening.