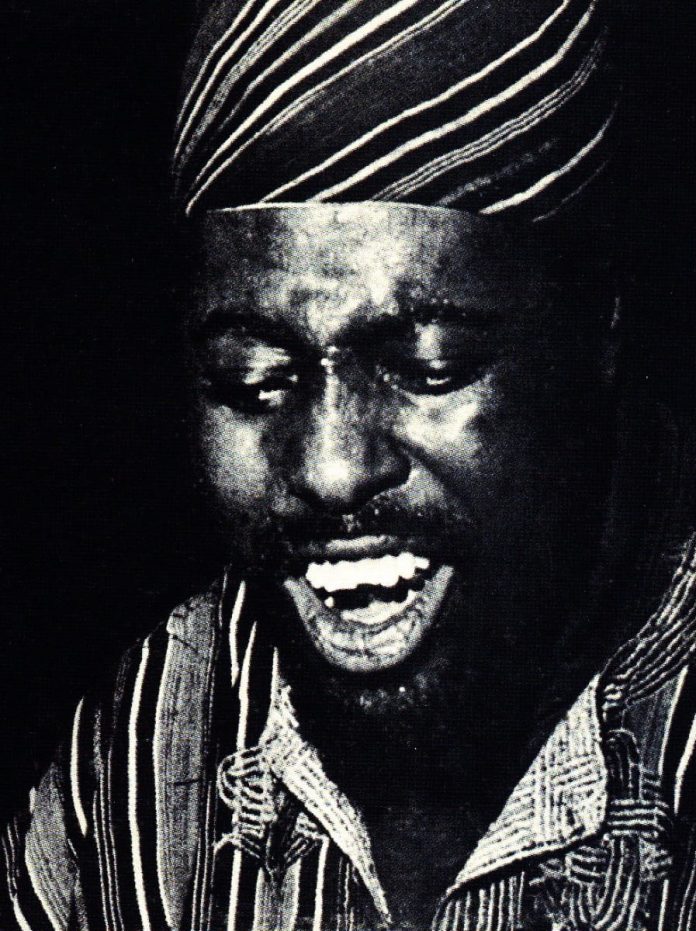

I doubt if readers will ever see much about Leon Thomas in the blues magazines, but this is hardly surprising, for Thomas must be classed as a border line blues singer – his talent extending into regions far beyond the limitations of the blues. Another possible reason for his neglect by the specialised blues writers is that he is a jazz-blues singer in the tradition of Jimmy Rushing and Joe Turner, and such artists do not come under their consideration.

‘Billy Eckstine, Arthur Prysock, and the wonderful B. B. King were among my favourites, but I think what really did it for me was when my younger brother brought home a record by Dizzy Gillespie that featured Joe Carroll, a kind of scat singing blues man.’

It is the all-round ability of Thomas to entertain and his intellectual approach to his music that impresses me. I had the privilege of interviewing him for a B.B.C. programme, during the course of which I began to realise that Mr Thomas was a very sincere and dedicated man, completely involved in his music and the future progress of both jazz and blues. A man who is a thinker, and deeply concerned with the world’s problems. What follows is the story of Leon Thomas, the man and his music, adapted from my tape and from the notes by Nat Hentoff published on the sleeve of his latest LP.

Leon Thomas comes from East St Louis, Illinois where he was born on October 4th 1937. Although his mother and father were not musicians, they both loved music – both sang in church choirs, and bought records for the phonograph – thus young Thomas always had music around him. ‘What is more’, he told me, ‘my parents did not just buy religious music, and didn’t confine themselves to popular stuff, they loved the old timers such as Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Blake – men like that, so you see, it was inevitable that some of this would rub off on me’.

He had many other interests and like most youths had a liking for sport. He was for example, a very good basketball player and at one time was contemplating turning professional, but in the end, the lure of music proved too strong. Nat Hentoff tells of his beginnings in music: ‘One Sunday afternoon, while he was in the tenth grade, Thomas went into a club for some cokes and for the music. The fiery centre of the proceedings was Armando Peraza, and eventually the youngster found himself on the stand, joining in on conga drum and bongos. A local musician told Peraza, ‘You can beat this kid on bongos, but not on singing’. Young Thomas was encouraged to return the next week to sing.

‘On stand then were Jimmy Forrest and Grant Green. Thomas sat in, this time as a vocalist, and among the intrigued listeners was disc jockey Spider Burke who had a weekly late afternoon radio show on which he played and showcased ‘live’ performances. Burke invited Thomas to the station, and the singer’s unique advanced method of scat singing, more fluid and faster than the traditional approach to jazz vocalese – quickly won him a substantial local following’.

By the time he was sixteen, Leon was beginning to change his mind about his future, ‘You see’, he said to me, ‘I was lucky enough to get myself a nice little air spot for my singing, and I was learning a song a week for the show. Besides this, the local club was employing me regularly. All the time I was there I was alternating with various groups that would be booked, and this was very valuable experience. I sang with some of the very best – Grant Green and the marvellous tenor Jimmy Forrest’.

I asked him who were his early influences. ‘Well, a number of men made an impression on me in those youthful days’ he replied. ‘Billy Eckstine, Arthur Prysock, and the wonderful B. B. King were among my favourites, but I think what really did it for me was when my younger brother brought home a record by Dizzy Gillespie that featured Joe Carroll, a kind of scat-singing blues man. I was excited and eventually found out that his ideas and mine were quite similar – but I had a little something more that I felt was my own. It was strange, I just wasn’t certain just where I was going, it was something unconscious; it was about then I heard John Coltrane, and I felt that here was something instrumentally that was rather what I was trying to do vocally’.

‘It was strange, I just wasn’t certain just where I was going, it was something unconscious; it was about then I heard John Coltrane, and I felt that here was something instrumentally that was rather what I was trying to do vocally’

To quote Hentoff again: ‘Thomas enlarged his audience, winning contests, coming third in a competition for the whole St Louis Metropolitan area. The same summer, a key event happened in terms of his development. Miles Davis was due at the Peacock Alley, and since Miles was a home town boy, there was even more anticipation than would be expected in any case. The local connoisseurs were also looking forward to hearing Sonny Rollins with Miles, but Sonny had just gone in his first self-imposed sabbatical, and John Coltrane was sent for from New York’.

Leon recalls that at first nobody understood (or wanted to understand!) what Trane was doing. ‘It was my brother who suddenly yelled at me – “Hey, don’t you dig? He’s doing what you have been trying to do for a long time. That’s your singing I’m hearing!” – and he was right – Trane was running all those changes, the same as me, but there was more to it. He was way into something very different, certain new ways of employing sounds to get a deeper, richer expression. I was there listening to him every single night – it was quite unbelievable. That rhythm section of Miles’ was also something else, Philly Joe Jones on drums, Paul Chambers on bass and Red Garland on piano. Oh yes, that was really quite something’.

When he had graduated from high school, Leon went straight to Tennessee State University on a drama and music scholarship. While at the university his love for athletics was still pulling him (‘I went all out for the track team, which I made!’). Nevertheless, music remained his first love and there were a number of fine musicians attached to the faculty, or doing graduate work – Les Spann, Hank Crawford, (a Ray Charles man for many years), Milton Turner and a Horace Silver sideman, Lewis Smith. Thomas smiled as he remembered those exciting days: ‘How could I ignore my music with those guys encouraging me all the time? I can tell you most of my second year was taken up with touring with a little group formed at the school. We played at Nashville, Kentucky, Alabama and other places in and around that area. The group broke up when Hank Crawford left to join Ray Charles. So I went to work at a club in Nashville called The New Era’.

The New Era attracted a lot of musicians and most of them told Thomas that he ought to go to New York and get into the big time. ‘Finally it was singer Faye Adams who clinched it – she was the only one who did more than give advice! She gave me the lead that sent me to New York, and I will always be grateful to her. I arrived in this city around September 1958 and in early October cut an album for RCA Victor. It was never released! This was a very great disappointment, for I needed some exposure.

‘I hung around the Shaw Booking Agency but days, weeks, but months passed with little work. I was about ready to give up and return home. Then when I was right down, my luck turned. Austin Cromer, who was starring at the Apollo, fell ill and I was asked to take over. This was a real chance. I’ll always remember that bill – Dakota Staton was singing there – and what a band; it included Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal and Nipsey Russell. The agency asked me if I had any arrangements for such a date. I told them yes, I had. Thank goodness Melba Liston came to my aid, and between us in three days of solid work we had some charts ready for rehearsal. Naturally, I was a little anxious as to how the Apollo audience would receive me. They are tough, you know!’.

Leon Thomas had no need to worry; the crowd loved him and he had to come back again and again to sing encores. ‘It was only a week, but Blakey too was finishing as he was going out on the road with a quintet from his big band. He asked me if I would like to tag along and I jumped at the idea. It was a experience and I kept on meeting cats everywhere’.

The year was now 1960, and in the south the black student movement for civil rights was changing from a dream to a reality, and Leon felt he would like to be near whatever was likely to occur. ‘I went back to Tennessee State – got a gig at a local club which helped to keep me solvent. I was around for a while. One night, it was my last at the club before I returned to New York, Count Basie, who had been playing a dance in the area, came in and heard me. “If you want a job with the band look me up”, Basie told me. Well, I opened at the Apollo and one of the first people I met was Joe Williams, who told me that he was about to leave Basie and go out on his own. He suggested that I call the Count’.

Basie was delighted to have Thomas, but as Williams was not yet all set to leave, the Count gave him work at his Harlem club every weekend. Times were now much easier for he was also able to work weekdays at the Café Wha in Greenwich Village with Booker Ervin, Richard Davis and pianist Jaki Byard.

In January 1961, Thomas finally joined the Basie Orchestra. It was a big step up the ladder for this was a band that produced star singers in a very short time. Both Jimmy Rushing and Joe Williams made their names with the Count. Unfortunately, his first stay with Bill Basie was extremely brief – one month! Then he was drafted into the army. However, it was not as bad as it might have been, for within six months Leon was back in civilian life. ‘It wasn’t too bad’ smiled Leon, ‘but of course, even this short time away had to be made up somehow, and I was a little while getting myself together. I gigged around a lot, taking jobs wherever they were offered, and all the time learning a little bit more. I joined Basie again in 1963 – and this time I stayed with him two years’.

Part 2 follows next month.