I don’t recall what tune the woman attempted to sing. I do remember her voice emerging as a sort of strangled caterwaul, rather akin to fingernails scraping a chalkboard. Swaying to the sound of the accompanying trio, she entered a trancelike state, pupils retreating upwards, revealing the unholy whites of her eyes. Art Blakey’s eyes had performed the same stunt when I saw him in Seattle with the Messengers in 1980, but this woman was clearly no Art Blakey. Mercifully, she finished assaulting the song to polite applause from the audience, leaving her mightily pleased.

Welcome to happyokai, the student recital. Formal music schools hold recitals, of course, but this one catered to the whims of wannabe housewife jazz singers “studying” with a local professional vocalist and voice coach. It’s a common social phenomenon here in Japan. The accompanying trio consisted of, as is usual, hired professionals, and the sensei also stood by, offering support and encouragement. It was held at a local jazz club, and I had gone there with friends to hear an acquaintance perform. I hasten to add she was not Ms. White Eyes.

Japan is jazz vocal crazy. Any forgotten jazz singer who made one record for Atlantic or Bethlehem in the 50s inevitably turns up on a CD as part of the Japanese reissue machine. For some, jazz and vocals are synonymous. When I’ve told people here that I like jazz, one response has been “Oh, who is your favourite singer?” Any given jazz performance is likely to include a singer in the lineup – it’s hardly considered a jazz performance without one.

These shows often turn out to be as much visual as aural. A lot of it has to do with atmosphere. People go to a jazz club to feel romantic and sophisticated, never mind what the musicians might be doing. The singers – many of them quite attractive to begin with – make up and dress for the part. They must spend a small fortune on their hair, nails, jewelry, shoes and gowns. They flash engaging smiles, their practised stage patter invariably bubbly and entertaining.

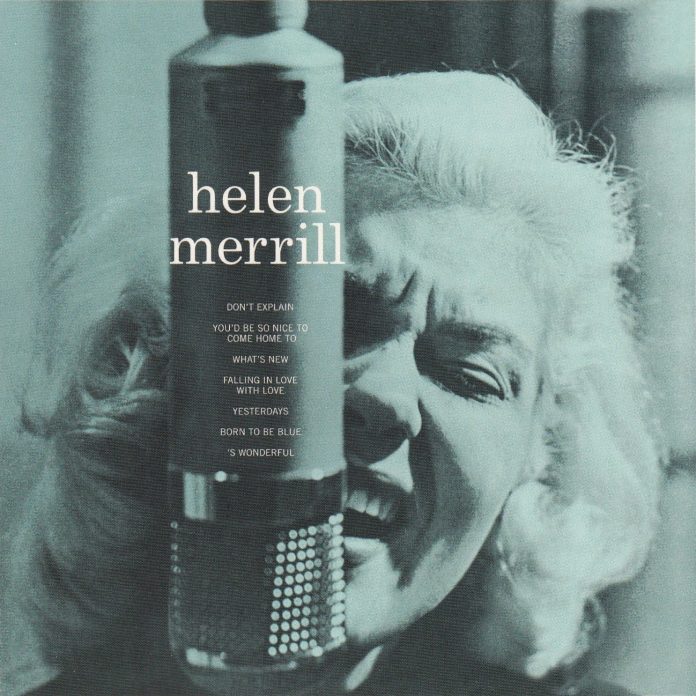

Sets are predictable, both in timing and programming. You can practically set your watch to start and end times. The set always begins with a couple of numbers performed by the piano trio. Then the vocalist sweeps in and begins to sing, probably an uptempo number like Lover Come Back to Me. After that, some patter, followed by a ballad, usually one of The Twelve. (That’s just how I refer to the same well-worn standards one always hears because it seems there are around 12 of them.) So expect to hear Misty, of course, or Over The Rainbow, All Of Me, Fly Me To The Moon, Wonderful World, My Funny Valentine, Summertime (no matter the time of year), maybe a Latin number like Boy From Ipanema and, surprisingly perhaps, You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To, popularised in Japan by Helen Merrill with Clifford Brown.

Joshua Breakstone: ‘I teach singers and the thing I stress is actually understanding music – which most Japanese singers do not – being able to do things with melody, knowing harmony, to be able to take ideas somewhere, etc’

As for the singers, many, shall we say, exhibit certain deficiencies. Often they can be heard bulldozing a song, confusing volume and forward momentum with intensity and swing. (Here one is reminded of the desperate sounds that can be heard emanating from a karaoke establishment.) Some sing with a vibrato wide enough to drive a truck through. Others seem to think if they sway or wave their arms around enough, it will look a lot like jazz. The visual aspect again.

Then there is the issue of language. Many vocalists speak only limited English, if at all, yet they sing almost exclusively in the language of the American standards that make up most of their repertoire. A bit of an accent is acceptable and even charming, but a listener ought to be able to understand most of the words. I remember listening to a singer years ago at one of the local clubs singing a familiar standard but warping the words so thoroughly I couldn’t pick up a single recognisable sound. It was surreal, worth experiencing for its own sake, but it wouldn’t fly at Birdland.

In my January 2007 interview with Eiji Kitamura, the veteran swing clarinettist explained how he felt about Japanese singers from a musician’s perspective: “When I play ballads I learn the songs before I play. There are some Japanese singers who don’t have true jazz feeling. When I play behind them I can tell, so it’s hard for me to accompany singers when that happens because my image of the song is quite different from theirs. Some singers don’t know what they’re singing. I think it’s necessary for them to study more. Sometimes Japanese singers sing loudly when they ought to sing more softly. Even with the clarinet, it’s necessary to play softly at times, but these singers don’t understand about being patient. Sometimes they should make a quiet sound. I think it’s a very important part of art.”

Kitamura is talking here about dynamics, and his analysis of some singers is spot on. It’s a viewpoint corroborated by Joshua Breakstone, an American jazz guitarist with considerable Japan experience. When I asked Breakstone to comment on the profusion of singers here, he emphasized the social aspect: “The Japanese love to sing, it frees them of the constraints that are evident in other aspects of Japanese life. For the millions who try to sing professionally, it’s really not professional as much as organising friends and fans to come to lives [performances] (in Japan there’s a very strong quid pro quo of support, you support your friends in some way or other and they do the same for you), and making your special memory evening where you are the star.”

And like Kitamura, Breakstone finds many singers failing to understand their role in the band: “I teach singers and the thing I stress is actually understanding music – which most Japanese singers do not – being able to do things with melody, knowing harmony, to be able to take ideas somewhere, etc., all the things I stress with instrumentalists. Singers need to be musicians and equal to all other musicians with whom they are playing at all times.”

To this latter point, it is also worth noting that a number of Japanese instrumentalists – beginning with Toshiko Akiyoshi and Sadao Watanabe right up to the present with pianists Makoto Ozone and Hiromi Uehara – have made names for themselves internationally. No Japanese singer that I know of has ever done that, language doubtless the reason.

Despite Kitamura and Breakstone’s reservations about singers, they’re not all that bad. Some of the rank and file standard-issue local vocalists are passable, and a few surprisingly good. I look at the better singers in part two.

See part two of this article