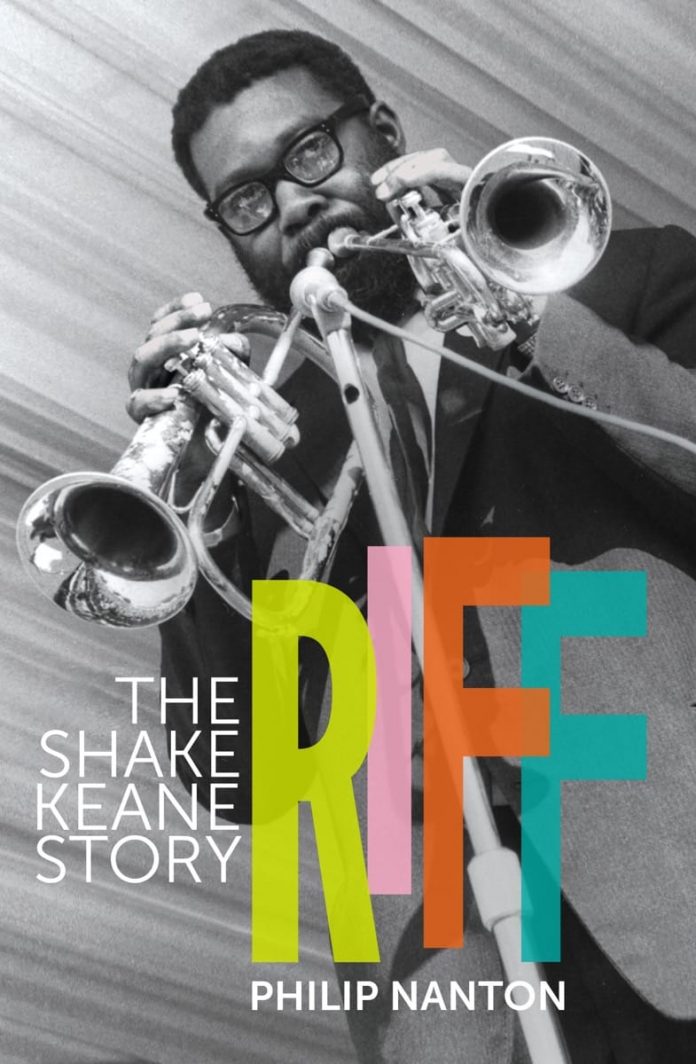

Ellsworth “Shake” Keane is probably best known for his six years as front-line partner in the Joe Harriott Quintet that recorded the innovative albums Free Form, Abstract and Movement, and for his involvement with Michael Garrick’s jazz & poetry events. He was an accomplished poet as well as an outstanding player on trumpet and flugelhorn, but Nanton shows that there were other strings to his bow, including sometime journalist, editor and actor.

Nanton, like Keane, was born in St. Vincent, one of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They first met in 1979, the year that the island finally gained independence from Britain. Keane was working as a teacher, having returned home to serve as director of culture for St. Vincent and the Grenadines from 1973 until he was dismissed in 1975, caught in the crossfire between politicians. 1979 also saw him awarded the Cuban Casa de las Américas prize for his poetry collection One A Week With Water. The two men would meet during Keane’s lunchbreak and became friends. Nanton thus has first-hand experience not just of Keane’s public music activities but a good insight into his private character, his literary, philosophical and spiritual interests, and his involvement in the cultural and political environment which shaped his work and personality.

The author pays proper attention to the socio-political aspects of the narrative, not least relating to Keane’s time in the UK. We have often heard how black American visitors to Britain and mainland Europe, whether servicemen posted here during World War II or musicians touring in the post-war years, were happily surprised to find how well they were treated compared with the overt and endemic racism they often encountered back home. However, the experiences of Afro-American visitors were somewhat different from those of immigrants from the “New Commonwealth”. Remembering the backdrop of racial tension and violence in Notting Hill where, off and on, Keane and some of his friends lived, a number of people have opined that Keane would have been more widely recognised and lauded if he had been white.

An artist’s work can never be entirely relied on to give an accurate portrait of their private character, but the impression of intelligence and sensitivity in Keane’s playing seems to be mostly reinforced by Nanton’s picture of the man himself – well educated, cultured, gregarious and generous-natured. That said, he had his grievous faults, and this book is no hagiography: conversations with two of Keane’s sons (the late, distinguished BBC World Service journalist Julian Keane and the adventurous, rather underrated trumpeter and photographer Roland Ramanan) revealed that Shake’s absence from and neglect of his families affected them emotionally, although it did not diminish their recognition of and pride in his considerable artistic talents. Ramanan mentions that Alan, their half-brother from Keane’s first marriage, was the victim of physical and psychological abuse from his father which led to his drug addiction. Alan’s mother, Christiane, suffered some abuse herself, but remained a staunch supporter of Keane as a musician.

The main text is, at 126 pages, relatively short, yet provides an intriguing and absorbing portrait of this multi-faceted man. The various appendices include five of Keane’s poems (excerpts from others appear in the main part of the book) and a selected list of his recordings.

Riff: The Shake Keane Story By Philip Nanton. Papillote Press, pp, 150pp + index (illustrated), £12.99. ISBN 978-1-9997768-9-3