Much of ‘Invocations’ suggests a kind of free-form Reginald Foort and I am prompted to ask what would have become of this LP had it not had Jarrett’s name on it. At the time of writing the package has been on the Billboard Jazz Chart for 14 weeks – and I promise you, had the release borne the name of an unknown musician, almost nothing would have been heard of it.

The album has nothing to do with jazz – and, to be fair, nobody is claiming that it does. But since Jarrett comes from a jazz background, the production merits a review in JJI.

I must say in passing that I find it a profoundly irritating affectation of ECM to eschew sleeve notes. It would be most helpful to anyone seeking to better appreciate Jarrett’s music if these performances could be situated in his total oeuvre. He is unquestionably neither a poseur or charlatan, but a master musician with very firm senses of direction and development. However, unless one is to devote oneself to an appraisal of the whole canon of Jarrett recordings – and there are very many – it is impossible to assess this as a sample of his total work. Even more important, the absence of a sleeve note means that one cannot even establish what Jarrett is setting out to do and cannot, therefore, offer a view as to whether he succeeds in his aim.

For a reviewer to make a purely subjective comment – on whether he likes it or not – just won’t do because musicians like Jarrett are entitled to a more profound evaluation.

Halfway through the second track of ‘Invocations’ a more coherent music seems to emerge from the oblique and random preamble – but this may simply be because my conventional ears are urgently looking for a hint of symmetry and acceptable musical logic. Whatever the reason, the music is oddly stirring and it culminates in a cathedral-like chord resolution.

Towards the end of Side One there is a passage of pastoral soprano with heavy echo, playing gracefully around an F minor root, which also falls pleasurably upon the ears.

Side Two features more echoey soprano – a sort of blue whale music – which evokes a mood but has little melodic content. Then comes a sombre, sepulchral organ passage with vague Moorish overtones, and then some long, sustained portentous chords followed by some drastic texture variations. It all sounds, however, as if Jarrett is playing at the organ rather than playing music on it.

The second album is, for me, a much more impressive one. Jarrett is a master of the acoustic piano; his playing is always poised and sprung and he creates a most brilliant, crystal sound. The five movements of The Moth And The Flame vividly exemplify Jarrett’s pianistic virtuosity and his skill in putting it to creative use to indicate the catholicity of his musical inspiration. There are strong church and gospel elements – often to be found somewhere beneath the surface of his music – some calypso feeling and an allegro passage evocative of European classical piano music and plenty of pure, quixotic Jarrett.

He has the musical vocabulary and technique to establish very quickly a wide variety of moods and idioms. He can switch dramatically from shimmering cadences and criss-crossing arpeggios of spectacularly accurate execution to slow, stately, reflective passages of haunting melancholy.

I can’t pretend to see any kind of unifying element in the music on these two records; but you cannot listen to the second without acknowledging that Jarrett is a fantastically gifted pianist.

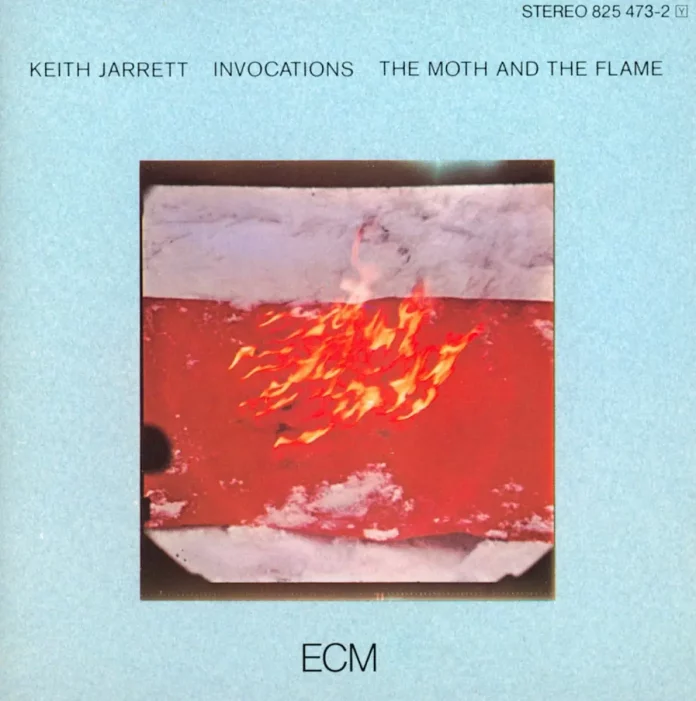

Discography

Invocations: First (Solo Voice); Second (Mirages, Realities); Third (Power, Resolve) (27.54) – Fourth (Shock, Scatter); Fifth (Recognition); Sixth (Celebration); Seventh (Solo Voice) (20.29)

Keith Jarrett (pipe org/ss). Ottobeuren Abbey, Oct 1980.

The Moth And The Flame: Parts 1, 2, 3 (30.57) – Parts 4, 5 (17.50)

Keith Jarrett (p). Ludwigsburg, Nov 1979.

(ECM 1201/02)