“This is a man’s, man’s, man’s world” proclaimed the godfather of soul, James Brown, whilst rarely ever acknowledging that this renowned anthem was co-written by his former girlfriend, Betty Jean Newsome. Newsome claimed in later years that Brown did not actually write any part of the song and regularly forgot to pay her royalties. Given Brown’s reputation and documented treatment of other musicians during his career, this claim may be difficult to reject.

Whatever the truth, it illustrates that getting noticed in the world of music is much harder for a woman than a man. Fortunately, there is currently no shortage of talented female musicians to remind us that their contribution to music is every bit as valuable as that of their male counterparts. Nor was there a shortage of female talent in the early days of popular music, it is just that men controlled the industry and wrote its history.

Take John and Alan Lomax: they were both highly respected musical anthropologists but you’d be hard pressed to find more than a few passing references in their work to the real role that women played in the development of the blues. In his book, The Land Where The Blues Began, Alan Lomax writes: “The blues have been mostly masculine territory. Of course, women have and do sing the blues. But down in the land where the blues began, the majority of real, sure-enough, professional and aspiring-to-be-professional blues singers . . . wore pants. Indeed, no truly respectable Delta woman was supposed to sing the blues even in private. Women sang the church songs.”

There is, of course, some truth in this. To join the black-folk’s church and be respected in your community at that time, a woman had to give up a lot of worldly things – especially dancing and the music of the dance. The blues was the devil’s own music and pity the sister who slipped and became attracted to that devilish blues music or, even worse, a blues musician. She might be cast out, lose her place in church and forfeit the support of the female community.

But if we take Lomax’s view at full face value, are we not also in danger of re-enforcing male-created stereotypes? Namely, that all good women went to church and sang hymns, whilst all bad women danced and sang to the blues? Was it really that simple or polarised? It certainly did not prevent bluesmen such as Son House, Big Bill and Muddy Waters from combining both music and ministry. But it may explain why most female blues singers we know more of – Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, Memphis Minnie, Bessie Smith etc – are all painted as lewd, brassy, bold and larger than life. They were being defined by men in order to conform to the images created by men. Even worse, they frequently had to behave this way in order to gain the acceptance of men. In practice, life for these women was inevitably more complex, more contradictory and less binary than male historians would have you believe. Check out Jackie Kay’s great biography of Bessie Smith as an example.

There can be no doubt that we have progressed a long way as a society in terms of our attitude to gender equality. But how far still remains a moot point. Even in music – where you would expect barriers to tumble the quickest – there remain obstacles. We are comfortable with women as folk musicians, singers of pop music and singers of jazz classics, but are we still not a little surprised when we see all-women rock bands, women as drummers and women as blues musicians? The German musicologist, Curt Sachs, articulated the theory that instruments like the guitar are shaped like a feminine body and have phallic necks. He suggests that holding and manipulating such a sex symbol in public seems to be an act appropriate only for men. It is an interesting male-created theory and many guitarists have been quick to exploit the sexual symbolism of a guitar for all it’s worth. But is that an exclusive male preserve? Ask Patti Smith or Chrissie Hynde and I wonder what response you will get! However, the fact that in 2021 we need a book written about women in the blues probably suggests that we still have some way to go along this journey.

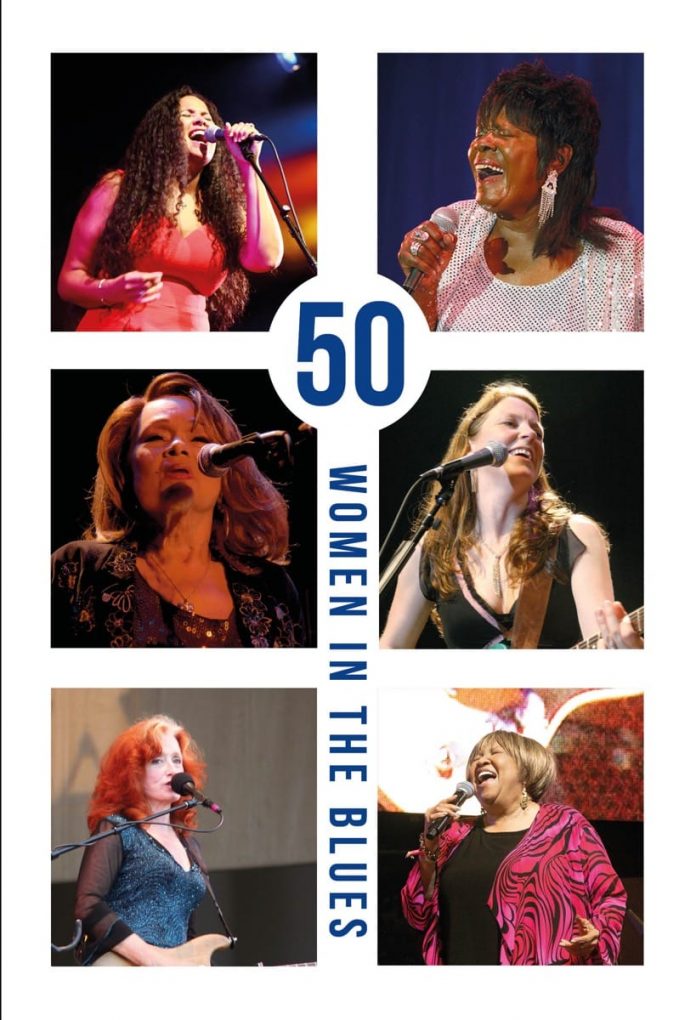

This book is the brainchild of American photographer Jennifer Noble. Now permanently resident in the UK, Noble has had a passion for the blues since seeing Muddy Waters in their shared hometown of Westmont, Illinois. After taking up photography in the mid-1990s, she made it a mission to capture as many legendary blues artists with her camera as she could. At that time, she lived in Chicago and was well placed to take photos in local clubs and festivals. Her photographs are published internationally and have been featured on many CDs. Having moved to London she now concentrates on visiting UK and continental blues clubs and festivals. Another mission has been to promote women in blues and give them greater representation in books and documentaries. She cites Koko Taylor as the first woman blues artist she saw perform; she has documented hundreds more since.

The choice of artists is always going to be subjective and open to debate. There is a mix of old and new; but the balance leans clearly towards the contemporary. The book starts with some short but unremarkable biographies of Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Memphis Minnie, Sippie Wallace, Victoria Spivey, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Big Mama Thornton, Etta James, Mavis Staples, Janis Joplin and Bonnie Raitt. But the next section, on current contemporary artists, is by far the most interesting. Given the author’s background, there is an inevitable bias towards American artists – some I have heard of and other I haven’t. There are a few UK artists featured including Kyla Brox, Dana Gillespie, Connie Lush and Sister Cookie. The photographs of all the contemporary artists are taken by Noble and the interviews take the form of a set of identical questions completed by the various artists. These clearly were not live interviews, but I have no problem with inviting musicians to contribute to the book in their own words.

Writer and musician Zoe Howe provides an excellent introduction to the book, concentrating primarily on the lives of earlier blues women and what it was like to lead an unconventional life. She makes the point that moving from town to town and forming casual relationships was outside the usual norms of the time and some were more comfortable with this than others. The call and expectations of the church were never far away, especially in the Deep South, and a woman had to be both tough and creative to survive. It is interesting to note how many female blues artists of that era eventually turned their backs on the blues and returned to the church. But that also had as much to do with a changing musical scene than a troubled conscience.

The only limiting factor with this book is its title. There are few artists who rigidly stick to one genre and consequently artists like Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone and Cassandra Wilson are excluded, even though they can sing the blues as well as any female artist. However, the book makes a timely and useful reminder about gender equality in music. It reminds us that blues women played a more important role in the development of the blues than has previously been ascribed to them by male historians and shows that there is a no shortage of women musicians active in the world of blues today. I will certainly be taking time out to check on some of the blues women in this book that I have not heard before. Judging by early results, I think I will be in for a treat. Recommended reading for those blues fans who want to believe that the blues has a fairer future.

50 Women In The Blues by Jennifer Noble (introduction by Zoe Howe). Supernova Books, 240 pp, pb, £19.99 from supernovabooks.co.uk. ISBN 978-1-913641-19-1