Jesus may have walked on water but he never beat a rhythm on it like Han Bennink. Astonishingly, the 78-year old maverick improv musician from the Netherlands eclipsed his creation of water music with 1982’s Airdrumming, a title that says it all and is nothing if not miraculously enchanting. “Been there, done that” is an understatement. Bennink accompanied singer Rita Reys and Eric Dolphy on the progressive giant’s Last Date. He swung with Johnny Griffin and Dexter Gordon and entertained raving Japanese fans with the floor as his sole instrument. That was decades after Nina Simone danced like a dervish on the sounds of Bennink’s tabla.

‘I admire Sonny’s wisdom and spiritual outlook. Furthermore, I can’t keep from crying whenever Sonny plays a ballad. I distinctly remember the good cry I had during his last performance at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam’

Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry and Ethiopian singer Jimmy Mohammed are on Bennink’s resumé. Last but not least, he has been the heartbeat of Instant Composers Pool, the avant-garde outfit that he co-founded with pianist Misha Mengelberg in 1967 and which harboured such European free improv pioneers as Willem Breuker, Derek Bailey and Peter Brötzmann.

Bummer: ICP’s existence of 50-plus years is threathened by the government’s repeal of its annual funding. “It’s ridiculous! We’ve been at the vanguard of creative music ever since our inception. Luckily, we’ve got a lot of support and I think my enthusiasm of playing with ICP is showing. We’re planning to add performances as street musicians to our schedule. Back to basics. It’ll create a buzz. It’s time to learn those bureaucrats a lesson.”

Blessing: “Some health issues have been worrying me, but I’m still going strong. I have been regularly cooperating with young guys, such as guitarist Reinier Baas and saxophonist Joris Roelofs. I created the visual package for an upcoming release, the Café OTO session in London. Last but not least, November 2020 will see the release of my performances with Sonny Rollins in 1967.

“I’m absolutely elated! Live In Holland will contain our gig in Arnhem, a studio session and the audio portion of the Jazz With Jacobs TV show, performed at the Go Go Club of pianist Pim Jacobs. Me and bassist Ruud Jacobs drove Sonny around in my raggedy Deux Chevaux. He was quite smitten by my houseboat on the Vecht river. He mistakenly thought it was seaworthy. I would’ve loved to sail away with Sonny.

“The performances still hold up after 53 years. Sonny is in prime form. Playing with Sonny is very special. It’s as if he carries you in his arms. As if you’re a cyclist in the slipstream of a tireless champion. I’ve always had two heroes: Louis Armstrong and Sonny Rollins. So for me that tour was an unforgettable experience. I admire Sonny’s wisdom and spiritual outlook. Furthermore, I can’t keep from crying whenever Sonny plays a ballad. I distinctly remember the good cry I had during his last performance at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Sonny has been intensively involved with our release on Resonance, which is typically Sonny and another thing I admire: while he sadly cannot play tenor sax anymore, he puts his heart and soul in his legacy, lectures and great interviews.”

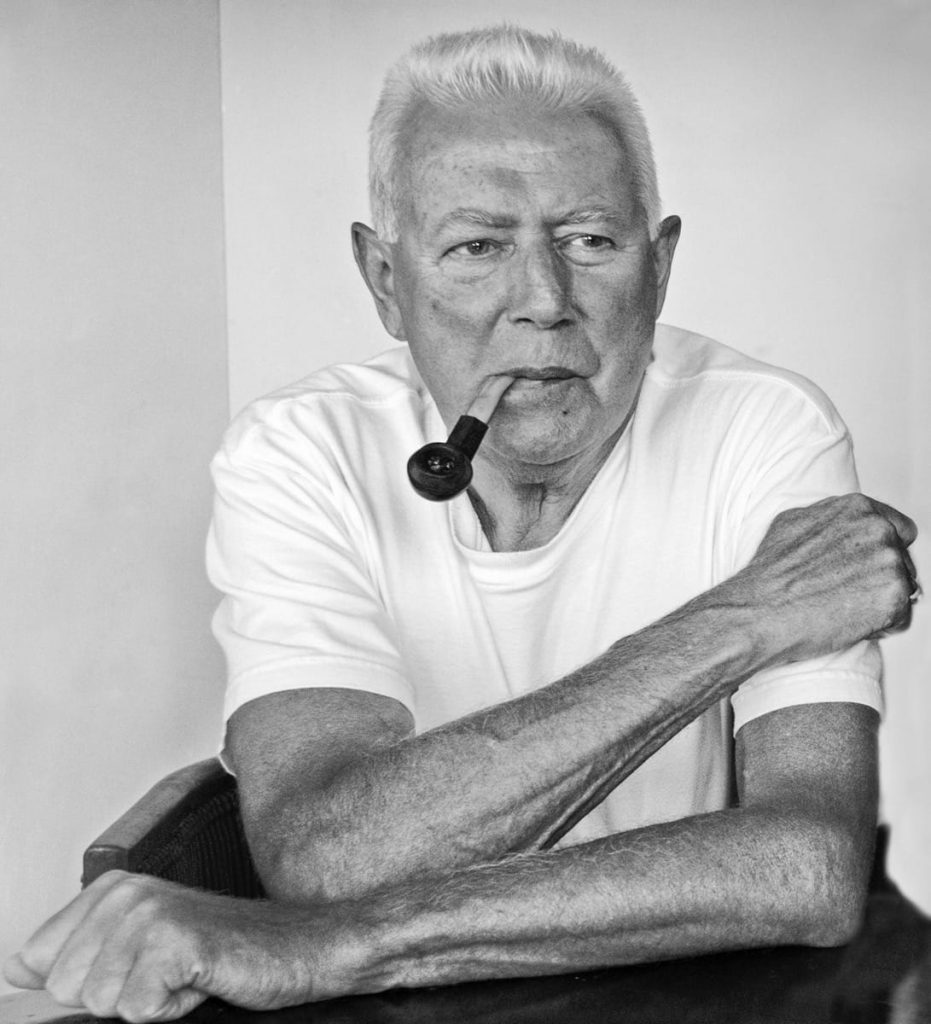

Bennink is 10 years Rollins’s junior. Seated in his music room and art space in the countryside of Drenthe, the drummer and acclaimed visual artist stares at the collage of Oceanic masks on the wall, seemingly pondering the waterfalls of joyful tears that he expects to shed in the ensuing years. If just for a sec, because Bennink’s mouth follows the winding paths of his mind. His self-proclaimed pessimism is at odds with his playful and spirited demeanor. Father of three grown-ups, he has the looks of a big, ruddy child. He looks back upon a happy childhood.

“I had the sweetest parents. My father was a professional percussionist and outstanding clarinet player that accompanied Vera Lynn and Judy Garland. He took me to his radio orchestra performances and let me sit in from a young age. Furthermore, I’m a real momma’s boy. My mum made my sandwiches until I reached the age of 24. Willie the Wimp! I would rather stay at home. I’m more of an adventurer in a musicial sense. It’s my life in music that got me on the road. However, I hate big cities. I think New York City is an awful place. If it wasn’t for music, I wouldn’t have travelled as far as Diksmuide, mum’s bag of sandwiches neatly arranged in my backpack.”

‘From the moment I stopped playing “time” with Misha in 1967, I was a traitor in mainstream jazz circles. I loved playing with American legends but the transition to my own thing was inevitable’

Bennink met more than a few bumpy roads on his avant-garde travels. “From the moment I stopped playing ‘time’ with Misha in 1967, I was a traitor in mainstream jazz circles. I loved playing with American legends but the transition to my own thing was inevitable. Essentially I serve two masters. I have always felt that playing tempo is not to be underestimated. I eventually resumed playing tempo, at which time people immediately said that ‘Bennink could still swing’. However, I feel that I’ve always kept swinging, certainly also when playing free. Freedom doesn’t mean anything if you don’t have the chops.”

In this respect, how would the versatile Bennink define his musical personae? “Nobody is totally unique. That’s no secret. I come from Baby Dodds and Kenny Clarke. But I’m always conscious of the fact that I’m nothing but a country bumpkin. So while I have been obsessed with African culture and rhythm, I never copy anything but instead use whatever feels appropriate. Basically, I’ve always veered towards disruption. Whereas, from our ICP pack, the English had a ‘pointillistic’ approach, the Germans veered towards bombast, Misha and I were anarchic. We were the Laurel & Hardy of avant-garde music. He was a nonchalant Belgian beer-drinking guy and I was the workaholic. He let me work so hard! But then, out of the blue, would come one mean phrase, exactly spot-on. It was a clash of systems.”

“See, Misha was into the art movements of Fluxus and DaDa and Brötzmann was a painter. We understood each other very well. DaDa, which is about the undermining of dogma and worn notions, is my DNA. Coincidentally, there was some DaDa going on during my recording session just yesterday. The bridge of Mary’s violin [Mary Oliver, Bennink’s ex-wife] suddenly snapped. It was quite shocking. A big bang! But I decided to let that be the natural ending of the piece. It is like an ‘objet trouvé’. I don’t like to plan things in advance.

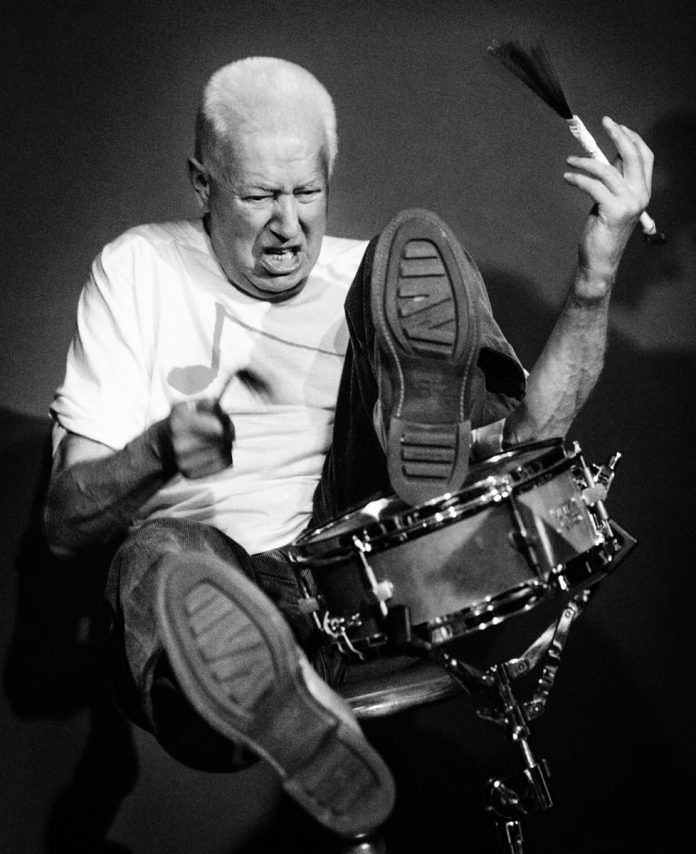

“I’ve been accused of making theatre instead of music. But it’s not theatre. It’s Pop Art. When I leave the drum kit, the perspective changes. Firstly, the acoustics. Secondly, the audience response. Thirdly, the musical interaction. I only step from behind my drumkit and mess about on stage if the situation calls for it, when I’m in the right company. If that company gives me an opening, I will not hesitate and jump through the cracks! When I play solo, no one knows what will happen. This makes me nervous as hell, but I usually end on my feet.”

Way back when, Bennink spent 10 maniacal years in a primitive, former livestock barn in the country, experimenting with a hodgepodge of instruments and appliances which he one way or another incorporated into his music: a gigantic Royal bass drum and Tibetan hi-hat, exotic horns, keyboards, cymbals and harps like gachi, dhung, rkangling, elong, khene, kaffir, rolmo, silnyen, oe-oe, violin, banjo, saxophones, clarinets, trombone, metronome, police whistle, cuckoo whistle, fire brigade bell, rattle, steel drum, musical saw, typewriter, garden hose and whip. “But then others expanded their set as well, which made it less interesting for me. I also became tired of hauling all this stuff around. I resumed playing on the basic kit. And finally I focused solely on the snare.”

The snare is standing next to us. On the ground beneath the snare stand three Bennink art pieces with brushes, among those a wagon he jokingly names the sweeper vehicle. “The snare, make no mistake, offers an endless variation of tones. This makes me think about my father. He had an unbelievably beautiful stroke. My grandfather was a plumber and my father was his factotum. He said that ‘the stroke must have the sound of a toss of peas in a zinc kitchen sink’. That’s a beautiful comparison. It has been my ambition to make it sound like that ever since. I did, lest we forget, also at times bring a bag of peas on stage for various intermediate effects.”

A sigh. A twinkle in the eye. “In the end, the woodpecker is the greatest drummer on earth. Right here is woodpecker country. All hell breaks loose during incubation time. The woodpecker’s single stroke is pure genius. It takes endless practice for me but it is very inspirational. I’ve always relied on improvisation from this kind of everyday perspective.”