Tenor saxophonist and composer Benny Golson holds the world record of writing no less than eight jazz standards: Stablemates, Whisper Not, Killer Joe and Five Spot After Dark, among others. He’s well known as a charming raconteur who sketches the background of his extraordinary career and compositions to audiences around the world. He usually readily admits: “I talk too much. But why not, my wife isn’t here”.

The good-humored, unpretentious jazz legend never fails to capture the audience’s devoted attention. The fact that Golson has been telling his stories for more than three decades does nothing to diminish their value as entertaining and essential jazz lore. He will reminisce, for instance, about his teenage friendship with John Coltrane in Philadelphia. The aspiring young musicians were dismissed by a local band. Broken-hearted, they went to Ms. Golson’s apartment. Benny and John laughed off her assurance that they would be famous one day. But when they met at the Newport Jazz Festival in the early 60s, Golson and Coltrane cracked up at the recollection of the bittersweet start of their careers, noting momma’s wisdom.

‘I used to drive a truck and deliver furniture. I hated it. So once I learned to use my imagination and write songs, I had found my vocation’

He’ll recount his pivotal role in reviving the career of the struggling Art Blakey. Golson organised a new band with fellow townsmen from Philly, Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and Jimmy Merritt. It was the period of Golson’s Blues March and Moanin’, the hit song by Bobby Timmons that would never have been in existence if Golson had not urged the pianist to add a bridge to his catchy lick.

Or Golson will chart in meticulous detail that fateful day in June 1956 when Clifford Brown was killed in a car crash alongside pianist Richie Powell and his wife. And comment on the process of writing I Remember Clifford, his dedication to one of the greatest trumpeters of all time.

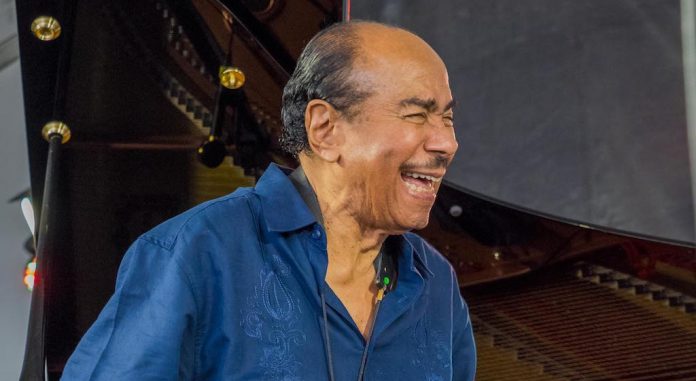

Our interview precedes Golson’s performance at Bimhuis, Amsterdam. Sound check is scheduled at four. The 90-year old Benny Golson has just woken from a well-deserved nap. He manages to look gracious in a casual, extra-large red and black flannel shirt. Dark, clear eagle eyes accompany the broad grin that could’ve been Cab Calloway’s. He cautiously seats his fragile body at the side of the bed. No worries. One loud, prolonged yawn and Mr. Golson is off the blocks. “If I wouldn’t be doing any better, I’d be scared!”

It has probably become more difficult to keep up your level of playing at your age. How do you cope with that?

I have to practise and stay in shape. If you don’t use it you lose it. That’s what happened when I moved to Los Angeles to write for the movie industry in the mid-60s. When I started playing again after more than 10 years, I had a lot of trouble to adjust. I played but nothing came! It felt as if I carried a tool instead of a saxophone. My chops and fingering were gone. It took a long time to feel comfortable again, years in fact.

And now you have to play more efficiently, I guess.

There’s no other way. Your whole constitution is involved and I’m not a young guy anymore. Strange thing is, you lose power but get more to the point. There’s no time or note to waste. At least I can still play. Sonny Rollins, one of the greatest improvisers of jazz, isn’t able to play anymore. It’s terrible, really terrible.

You’re one of the great composers of modern jazz. Do you still write?

Not as much. I’m too busy touring and playing. I’m not in one place for very long, that’s inconvenient. But I guess my writing is behind me.

When you were writing in the late 50s and 60s, could you foresee any of your tunes becoming popular and widely accepted?

No, you have no idea what’s going to happen. You might think you have a gem, but it doesn’t do anything. Then again you might think it is just a ditty and it is doing great. People always tell you what it is by how they accept it. You can’t foresee. Otherwise you would wake up and say, I’m gonna write a hit song! I have a lot of hit songs. These are the dogs that lie in the closet.

How many dogs are there, you think?

I don’t know exactly. A lot! I used to walk around dreaming up melodies. I was driven by something inside. Creativity, I guess. It’s like giving birth. How is the baby going to be? Fat, short, tall, slender, rich, poor, happy, sad? We writers are in the maternity ward, symbolically speaking.

First there’s nothing, then there’s a baby. What’s your take on this? A gift from God?

I have to leave that in the open. I’m not sure. Anyway it has to do with imagination. You bring something into existence that hasn’t been there before. It’s done intuitively. If you don’t have imagination, get a job driving a truck. To be sure, there’s nothing wrong with that. You have to make a living. I used to drive a truck and deliver furniture. I hated it. So once I learned to use my imagination and write songs, I had found my vocation.

Learning from Tadd Dameron: ‘Oh, so much! Harmony. He had this thing of making complex patterns sound simple… He had experience. Where I was weak, he helped me to become strong’

Tadd Dameron was your mentor as far as writing is concerned. You were both playing in the rhythm and blues band of saxophonist Bull Moose Jackson in the early 50s. What did you learn from him?

Oh, so much! Harmony. He had this thing of making complex patterns sound simple… He had experience. Where I was weak, he helped me to become strong. I had nothing in the bank to retrieve. He had a bank full. He was the piano player in the band of Bull Moose Jackson because he had been out of work and Bull Moose Jackson had told him, “Why don’t you join me until work picks up again?” I really looked up to Tadd. I picked that man’s brain so much, it’s a miracle he didn’t have to have brain surgery!

After that I was in Tadd’s band, which also included Clifford Brown. I remember one night in Atlantic City. Louis Armstrong dropped by. Tadd was acquainted with Armstrong and asked him to come join us for a number. Louis said “I don’t have my trumpet”. One of our trumpet players, Johnny Coles, lent out his trumpet to Armstrong. They played Sweet Georgia Brown. Louis Armstrong and Clifford Brown would take four bars each. Now Louis Armstrong was playing his style, which was fantastic, and Clifford Brown was playing the modern style. You sometimes hear people say that a certain meeting between famous musicians “should’ve been recorded…” Well, that should’ve been recorded!

You were on stage?

Yes, I was in the band, but could take it all in from aside. Fantastic! I wish I had my video camera at that stage in my career. I had a video camera, you know. My wife was filming almost every night. Finally it started to drive me crazy. So one night I said “Ah you don’t have to bring the video camera tonight, honey”. I was playing with Lionel Hampton. And that night… Milt Jackson showed up. Oh my God! And they both played on the same set of vibes, Lionel Hampton on the bottom and Milt Jackson on the top. And the video camera was in the hotel! Horrible!