The record company decided to give the lunch party at Ronnie Scott’s; on every table ham and chicken salad, four half bottles of wine, and handouts saying Buddy Rich had changed labels from Liberty to RCA. Invitations seemed to have gone out to half Soho. There were dealers, reporters, photographers, company executives and people who simply came in off the street, had lunch and walked out again. How they did this was unclear since the door was watched closely all the time. It was hot and smokey. Above the general noise and conversation the brash confident sound of his new album filled the club and shook Frith Street.

About 2,000 copies had been specially flown over from America because it couldn’t be brought out on time in England to fit in with the band’s tour of Europe. ‘Read the label carefully before you play it,’ said one member of the Rich entourage. ‘My copy was in the right sleeve but the record had Eddy Arnold and Kate Smith singing stuff like Will Santa Claus Arrive This Christmas. Some of these records got out and guys have been comin’ back to stores everywhere saying “What’s goin’ on”. The trouble is they make so many records at once at the factory. I tell you, mass production’s gonna strangle America.’

Amid all this Rich sat quietly in a corner drinking coffee and talking about the tour. The two-week itinerary seemed torture only endured by musicians; Spain, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, France, Belgium and Holland, finished by nine days at Scott’s. The band was in the middle of a short trip round halls in the provinces, with this line-up: Pat LaBarbera (ten/sop/flt); Brian Grivna (alt/fit); Jimmy Mosher (alt/sop/flt); Don Englert (ten/sop/flt); Joe Calo (bari/sax/flt); Lin Biviano (tpt); Jeff Stout, Wayne Naus, John DeFlon (tpt); Bruce Paulson, Tony DiMaggio, John Leys (tmb); Boh Peterson (pno); Paul Kondziela, Bob Daughertv (bs); David Spinozza (gtr); Phil Kraus (perc) and Candido (conga/bongos). Last night it had been a club date at The Opposite Lock, Birmingham; tonight, a two-house show at Croydon. He was staying at The Dorchester but had not been to bed yet. It was already afternoon. He was saying it would be hard tonight at Croydon.

‘There’s no way I can get the band to rest. Between shows there’s just no time at all. Audiences here are very receptive, very responsive, very warm. The band likes it here. Last night we played this jazz club, it was marvellous. They sold out completely. I enjoyed it because it was a jazz club and not a concert hall. I don’t really mind where we are playing so long as we are playing, but I think it’s easier for the band in a club. You are close to your audience and it’s more personal than a large auditorium when there’s distance between the stage and the people. It’s kind of an impersonal atmosphere. When you play a club you can see the way people are reacting and you can gauge whether what you’re playing is right. If something is wrong you can judge from the expressions and that way people can stop you going into the wrong groove.’

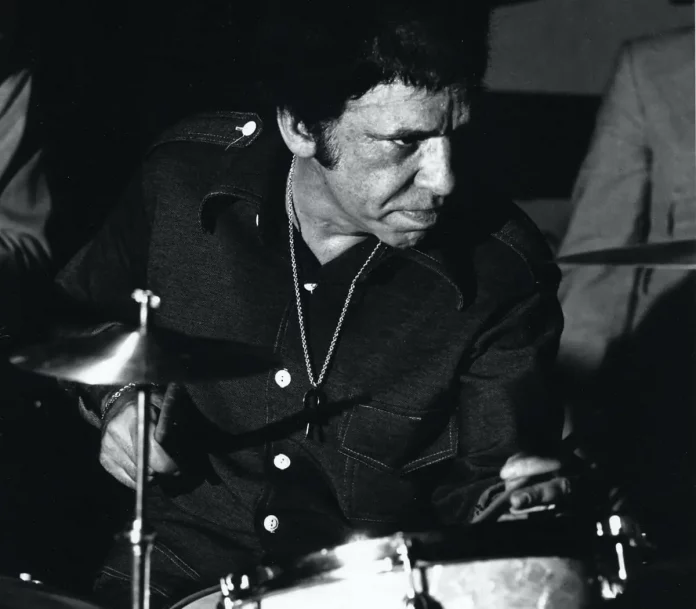

He was polite, highly articulate and, surprisingly for one with a reputation for being volatile, never quick-tempered with any of those who constantly interrupted him with requests to sign drums, records, or say that concerts were well reviewed in the music papers. Modishly dressed in a jacket, slacks and sweater in subtle shades of beige and brown, he wore tinted glasses and had a cross hanging round his neck on a gold chain. His hands were well-cared for and expressive. At times they would suddenly fan out when he was making a point, but the gesture was neat and economical. He looked young. It was hard to recall that before most of his present band was born he was on the road as a featured drummer with Tommy Dorsey in the early forties.

Now leading a band of his own he still does thousands of concerts and colleges. ‘People always say to me are the big bands coming back. I don’t know about them coming back like they did, that’s the nostalgic thing. That’s out of my bag completely. My band doesn’t try to relate to the past at all so as far as we are concerned, no. But we are back and totally successful. Musically we are successful, financially we’re successful, and in terms of audience participation we’re successful. We have shown you can take the contemporary music of today and join it to the big band form quite properly. It’s an unusual thing. Who says bands have always got to be tied to the forties?’

‘Look what’s been done by Blood, Sweat and Tears. They are the best. It’s a great jazz-oriented group. And look at Chicago. To my mind they are the two best young groups in America’

The sound system filled the room with a piece from the rock opera, ‘Jesus Christ, Superstar’. ‘There’s over 100 recordings of this but mine is the first one that has treated it as a jazz piece of music. We take the best of rock music and give them to the band’s writers and because they know what I want and because they are young they can incorporate my thoughts and their feelings on rock music and fuse the two together for the full orchestra. It’s not hard to do. Look what’s been done by Blood, Sweat and Tears. They are the best. It’s a great jazz-oriented group. And look at Chicago. To my mind they are the two best young groups in America.’

There was an interlude as somebody brought him a drum to sign and a reporter at the table said he thought everybody regarded Rich as the ‘greatest drummer in the world’. The leader grinned. ‘That’s very flattering but I don’t think there’s any such thing as the greatest of anything. I think I can play but a great many other drummers can play whatever bag they are into. I’ve heard a lot of trash being played, not just by drummers, by horn players too. It’s trash musically. I think the best young drummer I’ve heard is Bobby Colomby, who’s with Blood, Sweat and Tears. He comes from a jazz background and he’s been able to incorporate jazz with the thing he grew up with which was the form and so he plays that bag better than anyone I’ve heard. For that scene it’s Bobby.’

But did people spend enough time learning the basics before rushing out to buy a drum kit? ‘Well, you can’t expect a 19-year-old young man to have the experience and talent on his instrument that some other person has who’s been playing 30 or 40 years. That doesn’t necessarily mean age. If your mind is alive and you can hear everything that’s going on, accept the good and reject the bad, and keep involved in music then your experience can help you play better and what is more, understand modern fans and what’s going on around. The only good thing about the old days was that before you became successful you played in half a dozen different types of bands, a Dixieland band, a society band, a jazz band, a swing band, a marching band and things like that so you were able to play all those forms.

‘In the old days when you were hired you didn’t play one kind of music because the bands played for dancing. Your bands had to be able to play because when the leader called a waltz that’s what he wanted to hear. He didn’t want drum solos. There were no specialised musicians in those days. You hear people say oh, he’s a great big band drummer, or a small band drummer, or he can play rock. It’s one instrument and one music. The only thing that’s different is the concept. And you have to have that in your head, the conception of what you’re playing.

‘You weren’t a specialised musician in the old days. When the leader called a rhythm and blues chart, what they call rock now, you had to play it. You didn’t get up and say excuse me I gotta get out and find a rock drummer. You were the drummer and you’d gotta play drums. There’s too much specialisation today; he’s great with sticks but he can’t play brushes, a wonderful brush player but where’s the sticks, great with a small band, but lousy with a big band. If you can play your instrument you should be able to play anything that’s put in front of you and play everything well. If the public’s paying to hear you they have a right to listen to something worthwhile.

‘When you get these avant-garde musicians experimenting in front of an audience instead of in a rehearsal hall it’s embarrassing to me as a musician and I like to think that my ears are wide open’

‘Music is professional. Anything less than professional shouldn’t be allowed to be performed. When an audience is coming out and paying money they’re not coming to hear you experiment and try things you aren’t qualified to try. It doesn’t matter what they spend. They should be presented with the best and the total of what you have to offer. I think it is wrong to experiment on the bandstand like some of these new thing guys. To a layman’s ear jazz is very hard to sell. Very few people understand improvisation and are attuned to the changes in jazz. They want to hear a little melody. But when you get these avant-garde musicians experimenting in front of an audience instead of in a rehearsal hall it’s embarrassing to me as a musician and I like to think that my ears are wide open. You can do it in rehearsal halls, you can get it down to a point where an audience may be ready to accept it but some of the things I’ve heard are terrible. I’d be a hypocrite to say it was great because it’s not great at all. Very few things are really great.

‘Probably the last time there was a change of this type was in the bebop era but people were not experimenting with their instruments, they were experimenting with a form of music that was one step ahead of swing. People understood it because Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and later Miles Davis were so brilliant on their instruments. They could play, they could really play their horns. By that I don’t mean just improvise. They knew their way around the thing. The stuff they played was based on a melodic line, on the changes. Take a tune like How High The Moon. Now, that became a different melody but the changes were the same as How High The Moon.

‘A lot of what they do today is the blues and the blues have been around for a hundred years. It’s just a new concept on something old. As regards the new thing there’s nothing there you can hang on to, nothing you can say is nice, is melodic, is swinging, there’s nothing you can relate to. If you go to a club and see a guy on the drums he’s playing a solo behind the bass who’s playing a solo behind another guy who’s playing a solo, so you have four or five guys each doing solos. That’s not freedom, that’s mass confusion. When I go out I want to be entertained. I don’t want to work out mathematically what the guys are doing. I want to hear something that affects me emotionally. I don’t wanna be Einstein.’

Everybody laughed and he got up to shake hands. Company executives came over and he was away to talk business elsewhere. A few minutes later a group who had been at the table got their coats to leave and stood for a few seconds at the door. ‘What’s that?’ said a passer-by, stopped by the music coming into the street from loudspeakers. One of the group replied, casually, the urgent voice still in his mind: ‘The Buddy Rich experience,’ he said.