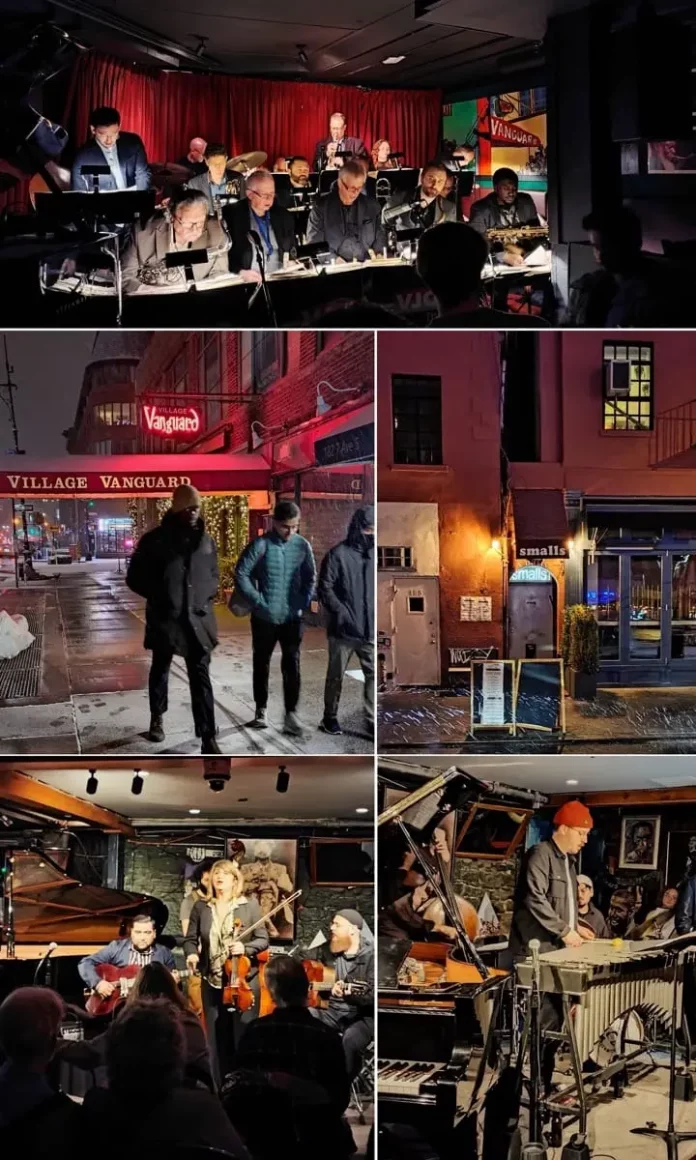

Manhattan’s first snowflakes in almost two years began to fall as I headed down the narrow steps to the subterranean Village Vanguard. The world’s oldest jazz club hasn’t changed in decades, except for the prices. The pay phone is still on the wall next to the modest green room/office – wonder which of the giants spoke on it? They all played here, of course, and often recorded as well. There are plenty of gentle ghosts here; one almost expects to hear the glass-tinkling, laughing woman from the Bill Evans Trio’s Sunday. Now audiences are sternly forbidden from talking, using their phones or taking photos during the sets, and there’s no food.

In the dimly lit, low-ceilinged main space, it’s hushed even before the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra begins its Monday-evening session. It’s done so weekly ever since 1966, shortly after it was founded as the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, making it the longest-running steady engagement in jazz history. “It’s nice to have a regular gig,” said trumpeter Terell Stafford with a grin at the end of the evening’s second set. The longest-serving member is Dick Oatts, who’s been playing alto, flute and clarinet in the band since Jones hired him in 1977.

The 16-member band (with one woman subbing on trombone) packs into one corner of the odd-shaped, nearly triangular room. The 130-seat venue’s acoustics are notoriously tricky, especially around the drums. With a big band, the sound can get a bit piercing at times, but the VJO sent sweet (and salty) waves of sound washing over the audience, who sit close to them on two sides.

Stafford, who played with McCoy Tyner and organist Shirley Scott, delivered the set’s fieriest solos, setting off combustion in his fellow players. John Riley, who’s held Lewis’s drum chair for more than three decades, has clearly developed the optimal discreet playing style to please the mysterious sound gods and goddesses of the room, providing subtle backbone to the ensemble without ever getting heavy-handed.

The core of the set was Thad Jones compositions, like the toe-tapping Blues In A Minute, a perfect vehicle for pianist Adam Birnbaum. Another, 61st & Rich’It, was a lilting, 60s groovy cinematic tune that brought to mind Basie and Mancini. It was written for the band’s longtime bassist Richard Davis, with his successor David Wong providing the kind of nimble, melodic solo that is so rare (ghosts of Scott LaFaro).

There was also a breezy, loungey 60s feel to a Tribute To A Statesman, a Jones tune new to the band that was still being worked out onstage at the last minute. That shows in a slightly ragged ending after a tandem solo by two trumpets. The band plans to record the tune soon at the club for a forthcoming release, its first in 10 years. It’s been a while, but a decade is a blink of the eye for this lively behemoth.

Valet and Voilqué at Smalls

My evening began at Smalls, a five-minute walk down Seventh Avenue. Another cellar establishment known for live recordings, the 74-seat club opened 30 years ago. There’s a warm, cosy feeling in this cellar, with a painting of Miles glowering on a brick wall and a miniature Buddhist temple with votive candles behind the bar. After barely surviving the pandemic (and 9/11), Smalls is now thriving. There are two bands every night plus two more at its sister club Mezzrow across the street, along with weekend afternoon jam sessions. Most shows are streamed and archived online.

The final night of New York’s French Quarter festival brought two Parisian bands to Smalls’ cramped stage. Actually, it’s not a stage, just an end of the cellar close to the bar, with waitstaff constantly flitting across the front, making sure that each guest buys their minimum one drink per set.

First up was vibraphonist Alexis Valet’s quintet, playing originals from a new album due this spring. His compositions range from poignant to knottily complex. The first tune, Following The Sun, seemed a bit disjointed, with angular solos by the leader and saxophonist Jerome Sabbagh seemingly at odds. Drummer JK Kim and bassist Joe Martin worked to hold things together, while pianist Tony Tixier just hung on, eyes glued to the sheet music.

The sound became more cohesive on the ballad Mascara, named for Valet’s mother’s hometown in Algeria. Tixier shone with an unabashedly romantic solo with surprising, light leaps and trills, Kim’s drumming was supple, and Valet’s mallet-work was warm and shimmering, as on a later ballad, Laika.

Valet’s tone ranges from rich and buttery to a metallic, gamelan-like clang, sometimes restlessly riding the crest of his band’s propulsive rhythm section, including Tixier’s piano. Martin offered a drum solo that flowed like tropical rain that never quite builds into a storm. He and Sabbagh recently recorded with Kenny Barron and Johnathan Blake, suggesting the level of improvisation here. Sabbagh, a Parisian Brooklynite, has a conversational style with many tangents, played on a rich-toned 1920s Conn saxophone, a decade older than the world’s oldest still-operating jazz club.

The evening warmed up with an unplugged, drumless jazz-manouche set by Aurore Voilqué, an eloquent violinist in the Stephane Grappelli school, her fiddling fluid and fancy-free with never an uncertain moment. She also sang loose, rough-edged vocals – upstaged in that department with a guest appearance by a more refined French jazz vocalist, scat virtuoso Cyrille Aimée.

Voilqué’s main foil onstage was lead guitarist Simba Baumgartner – great-grandson of Django Reinhardt – who played dizzying, intricate runs worthy of his forefather. They were ably backed by two locals, stand-up bassist Dylan Perrillo and rhythm guitarist Josh Kaye, a London-born Brooklynite who also plays oud in Middle Eastern band Baklava Express. Voilqué led an audience sing-along on Charles Trenet’s bittersweet Second World War hit Que Reste-T-Il De Nos Amours (aka I Wish You Love), and concluded with a sizzling, ever-accelerating version of Dark Eyes, dedicated to a Ukrainian-Russian pair of friends in the audience, with hope.

The Village Vanguard and Smalls, 15 January 2024