One informal theme of this recently rather irregular column – for which, apologies – is misremembering or sometimes downright forgetting. I’ve recently been involved in a wholesale audit and reorganisation of the LP archive, mindful of the splendid Mats Gustafsson’s mantra to the effect that a vinyl a day keeps the doctor away, more than usually relevant advice in these times. It’s hardly surprising that certain records and artists are overlooked, but I’ve recently stumbled across a couple of artists I’d almost completely forgotten.

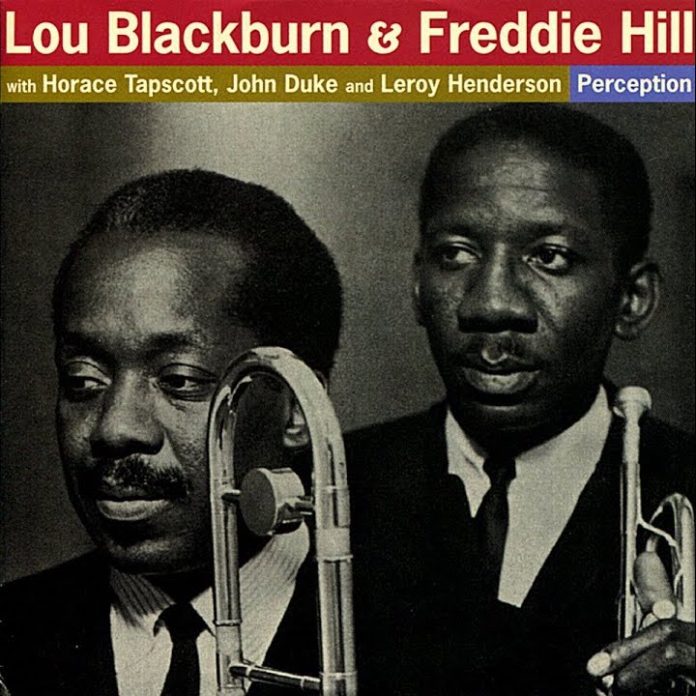

The first was trombonist Lou Blackburn, one of those blink-and-you’ll-miss-him recording artists who popped up for a moment, made a couple of discs, and then effectively vanished. You don’t even find his name mentioned in surveys of the 1960s California scene. Lou made a couple of records for Imperial in the winter and spring of 1963, Jazz Frontier and Two-Note Samba. You’d know at once that it isn’t J.J. playing. The solos are competent rather than dazzling and the writing pretty workmanlike, though I really enjoyed the waltz-time Blues For Eurydice. In truth, Blackburn is rather blown out of the water by his front-line companion Freddie Hill and when Blue Note reissued these discs in the late 90s they gave the two hornmen equal billing, which nudged Lou even closer to obscurity.

Fresh Sound also picked up the dates, reissuing them as Perception, so the guy hasn’t been entirely forgotten, but he pretty much disappeared from view. Listening to the records again, I dimly remembered – those two words seem ever more closely conjoined – that he had relocated to Germany and spent his last years there. I did a bit of digging around. Apparently, he was a busy session guy, which fits with the neat, accurate, not very obtrusive or emphatic playing, and that he turns up on records by the likes of the Righteous Brothers and The Turtles. I’ve not been able to find his credit there, being a bit of a Turtles nerd, and doubtless he pops up on soundtracks of the time. His period in Germany is more interesting. It seems he formed an Afro-pop band there called Mombasa, which rings a (yes) dim bell from the days when I used to bus and train round the country, blagging entry to shows on spurious journalistic grounds – I did once claim to be the jazz critic of The Tablet, and now, 40 years on, find myself the Scottish correspondent of The Tablet, which just proves that if it’s for you, it won’t pass you – and trufflehounding free food. So maybe I saw Mombasa down the bill at something. I certainly saw Osibisa in Germany, which could mean I’m conflating my Afro-rock.

I remember asking Ginger Baker about Tony Allen. “’E’s a genius … the bastard”. That counts as a gusher from Ginge

On which approximate subject, it was sad to learn of the death of Tony Allen, the one-time associate of Fela Kuti and a man who probably deserved more than any other could the title of world’s greatest drummer. Tony famously dismissed admiration of his polyrhythmic genius by saying that riding a bicycle involved using four limbs doing quite different things. True, but the comparison borders on false modesty. I remember asking Ginger Baker about Allen. “’E’s a genius … the bastard”. That counts as a gusher from Ginge. Allen’s more recent work has been patchy but the reconstructed album with Hugh Masekela is a current favourite.

The other forgotten “star” I turned up during the recent trawl was pianist Charles Bell, whose Contemporary Jazz Quartet put out two records, in 1961 and 1963, on Columbia and Atlantic. Apart from a live recording made at the Carnegie Lecture Hall a bit later, that’s all I know of him. Apart from the fact that his son is another great drummer, Charles “Poogie” Bell, who would have been a newborn or not yet born when the Columbia record was made. It borders on Third Stream, with titles like Counterpoint Study #2 and Variation 3, but the music isn’t as academic as that makes it sound and actually swings quite hard. The second record is mostly repertory stuff, but it benefits hugely from the presence of Ron Carter on bass. Ron gives the piano, guitar, bass, drums format a bit of “middle” and weight, as well as distinctive countermelodies. Bell is well represented on two Fresh Sound issues.

The live record was made in November 1963, early in the month but somehow already foreshadowing the gloom and shock that followed Dallas. I’ve never heard On Green Dolphin Street done with such sombre hues. Perhaps fanciful to “hear” what may simply be a stylistic turn in Bell’s music. There wasn’t, as far as I know, a sequel and he goes down in history more as Poogie’s dad than as an imaginative musician in his own right.

Incidentally, you might be attracted to the Lou Blackburn records by the news that Horace Tapscott, later to be a hero of the California avant-garde and founder of the Pan African People’s Arkestra, is the pianist. Sad to relate, he’s rubbish, barely competent, which only goes to show. West Coast Hot was still a year or two away, but, damn, he must have practised hard in the interim.

I’m only at B…