Swing to the left

During the 1930s, and particularly around the time of the Spanish Civil War, it first became fashionable to profess to being a communist. Many ordinary people were drawn in, particularly since nobody was then aware of the horrors and injustices being perpetrated in Russia at the time.

The FBI put the finger on Duke Ellington as being a communist. Undoubtedly, like many good-hearted people at that time, Duke’s sympathies lay in that direction and he was obviously set against uncivilised regimes like that of General Franco. Duke raised money for left-wing organisations – an understandable practice for someone who was persecuted by the white regime.

Duke did not have the freedom to act without the FBI following each of his moves. Here’s the beginning of the file the Feds kept on Duke. I’ve retained some of the antique punctuation because to change it would lose sense of the paragraphs.

The May 12 1938 issue of the “Daily Worker”, an east coast Communist newspaper, contained an article captioned “Harlem Youth Parley Rallies for Jobs.” This article listed Duke Ellington among the prominent endorsers of the first All-Harlem Youth Conference which was to be held on May 13, 1938 in New York City. The All-Harlem Youth Conference has been described as “among the more conspicuous Communist-front groups in the Racial—-subclassification” by the California Committee on Un-American Activities in a report issued by that group in 1948….

According to a reliable source Duke Ellington appeared on a list of the Committee of Sponsors for a dinner given at Ciro’s Restaurant, Hollywood, California, on November 10, 1941. The dinner was given under the auspices of the American Committee to Save refugees, the Exiled Writers’ Committee, and the United American-Spanish Aid Committee. “The American Committee to save refugees has been cited as a Communist front by the Special Committee on Un-American Activities in a report dated March 29, 1944; the Exiled Writers’ Committee has been described by the California Committee on Un-American Activities in its 1948 report as ‘established by the Communist League of American Writers to be later the Communist front, American Committee to Save Refugees. The Exiled Writers’ Committee worked with other Communist fronts in the Spanish Communist refugee education and the United American-Spanish Aid Committee has been cited by the Attorney General of the United States as within the purview of Executive Order 9835.’

The 1944 report of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, which described the Artists’ Front to Win the War as a Communist front, listed Duke Ellington as a sponsor of that organisation at the time of its debut at a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall in New York City on October 16, 1942.

The June 23, 1943 issue of the “Daily Worker” contained an article captioned “Negro Tribute to Hit Back at Axis Plot Here.” This article related that Duke Ellington among others was to appear at a program to be held on June 27 1943 designated as a “Tribute to Negro Servicemen.” The article stated that the program was to be supported by the Negro Labor Victory Committee and the National Negro Congress, among other organisations. Both the afore-mentioned organisations have been cited by the Attorney General of the United States as Communist within the purview of Executive Order 9835.

Speaking through music

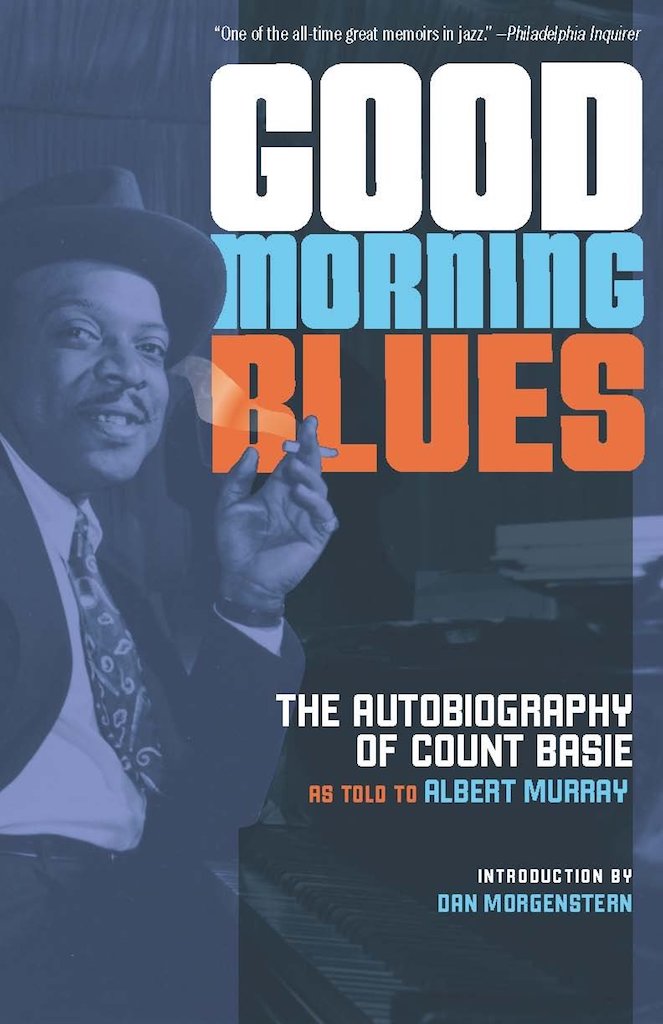

One of the saddest books in jazz literature is Good Morning Blues, The Autobiography Of Count Basie (Heinemann, 1985). I once tried to interview Count but, as was quite often the case, he was both friendly and monosyllabic. I can sympathise with Albert Murray, who wrote out this flaccid and very disappointing volume. But Count spoke through his music and here he was more than eloquent! I suppose I must have reviewed Basie’s Beat (Verve V(6)-8687) because I had in my collection two LP test pressings. Dave Bennett put them onto CD for me and created a magnificent box for them.

Basie’s Beat ranks as the best from what we must regard as the later period of Count’s recordings.

To my amazement the album has never been issued as a CD. I think it ranks as the best from what we must regard as the later period of Count’s recordings.

The Basie band had become progressively more polished as the years passed and was to be even more so in its final throw. But here, in the middle of all that, there’s a loose feeling to the two sessions which was out of character for the times. The band really sounds as though it’s enjoying itself and even Freddie Greene unbends to the point of playing single-string guitar in duet with Al Grey at the beginning of a magnificent St Louis Blues.

I remember having a chat with Al in 1957 or ’58 when he’d just joined the band. He was bursting with enthusiasm and told me that Basie intended that Al should be taking over all the trombone soloing in the band. This caused unforgettable fallen faces when I told my two pals Benny Powell and Bill Hughes, who had for a decade shared the parsimonious solo space allotted to the instrument.

Al was right and he soon came into his inheritance. But, in 1961 Grey had broken a bone in his foot and Basie fired him on the spot. The mild-mannered Count had form for this kind of savagery. It meant little to him when his baritone player Charlie Fowlkes broke his hip in 1969 after 18 years with the band. He was out. Charlie returned in 1975 and Al came back, too in 1964.

It was in his second stint that Al really flourished. Many people thought him a bebop player, but this was a deception that he achieved by playing his mainstream in double time. He was very adept with the Tricky Sam Nanton wah-wah mute style, but Al treated this as a novelty, whereas with more substantial jazzmen like Quentin Jackson and Tyree Glenn it was a way of life.

Anyway, St Louis Blues on this album is a remarkable all-round success, capped by the main soloist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis on tenor. Eddie used to heft his tenor from hand to hand as though it were made of balsa wood. I loved his playing and found it some of the most exciting in jazz, but often thought I could be mistaken, because Alan Morgan, whose comprehension and knowledge of our music was far greater than mine, thought Lockjaw was a washout. The band loosened up joyfully through this head arrangement and with Count indulging his piano there’s an overall feel of Kansas City in the air.

Al has another showcase in Thad Jones’s arrangement of Makin’ Whoopee, on the album but also familiar in concert.

I wanted to write about the best album Count ever made in Scandinavia, called Count Basie In London (Verve) but I’m out of space, so it will have to wait.

Chris Barber

Unlike Kid Ory or Jim Robinson, Chris Barber studied music at the Guildhall, which gave him an advantage. He bought his first trombone second-hand for six pounds ten shillings from a hard-up Harry Brown.

Ken Colyer’s taciturn lack of ability to communicate was compensated for by his immensely voluble brother, also in the band and who, in the manner of a ventriloquist, did Ken’s talking

My memory of first hearing a Barber band would be that it was in 1949, but the reference books suggest it must have been 1950. Whenever it was, there were two trumpets – were they Dickie Hawden and Ben Cohen? And Alex Revell was on clarinet. The music was far more wide-ranging than it later became, and I remember particularly a wonderful version of Makin’ Friends with the Teagarden speciality featuring Chris’s trombone. That band played with a unique spirit and fervour, and was particularly notable for its musicality. I always missed the spirit of the free-sounding first band.

In between that band and the Halcox/Sunshine group, of course, came the Ken Colyer band. Ken’s taciturn lack of ability to communicate was compensated for by his immensely voluble brother, also in the band and who, in the manner of a ventriloquist, did Ken’s talking and rivalled Beryl Bryden if not in size then in bad washboard playing.

As a merchant seaman Colyer jumped ship at New Orleans in 1952, and played with George Lewis and other local black musicians. Since such black and white fraternisation was illegal in the Crescent City, all the musicians were in danger of trouble with the law. When the law decided to deport Colyer back to England, Chris Barber magnanimously agreed to hand his band (with Monty Sunshine and Lonnie Donegan) over to appear under Colyer’s apparent leadership, with Chris holding the reins behind the scene.

Colyer, who had a huge opinion of his own talent, decided to sack bassist Jim Bray because he didn’t swing, Lonnie Donegan because he couldn’t stand him (“Nobody can stand Lonnie Donegan”, Chris pointed out), and drummer Ron Bowden because he was “too modern”.

….the banjo worked on me like a crucifix does on a vampire, and its constant presence held back forever my full appreciation of this otherwise excellent band

Chris reminded Colyer that the band, which was a co-operative, had trouble putting up with Ken’s drinking and fired him instead. The band became the Chris Barber Band, Pat Halcox joined and Chris vowed never to hire drunks and to always pay his sidemen well. The formula established the band for the next 70 years, and, unusually, he experimented at length with electric instruments within the boundaries of the music that he loved and saxophones gained a regular presence in the line-up. Despite this liberal thought, he nearly always used a banjo. I was prejudiced in this regard, because the banjo worked on me like a crucifix does on a vampire, and its constant presence held back forever my full appreciation of this otherwise excellent band.

Barber bands were always very musical, and Chris was an outstanding player who was never called on to work at the limits of his formidable technique.

Now the time has come for Chris to hang up his horn. A bad fall at the beginning of the year in which he broke his hip and needed a replacement, really signalled the end of his career – he’s spent the intervening time in hospital, and Kate, his wife, says that he has now fully retired.

Fully trained as a classical player, Chris had all the attributes and his fervour and intelligence – coupled to a remarkable and pretty original instinct for jazz – led him through a colourful career. He earned enough money to be able to choose to bring over from the States great musicians like altoist Louis Jordan and a host of singers. His band’s popularity is apparently even greater across Europe than it is here.