The tall figure of John Scofield and the posh Amsterdam hotel room are like fire and water. Dressed in jeans and a woodchopper shirt and sporting a long grey beard, he looks like the guy driving a pickup truck with a bumpersticker that says “God Bless John Wayne”. At the retirement age of 66, the passionate player and endorser of Ibanez guitars goes full-steam ahead. He has a relatively new album – Combo 66 – in his hip pocket and a heavy touring schedule that scares off even the most eager of young lions.

‘You can still teach me some bebop. I’m a rock guy. I grew up in the late 60s. That’s my point of reference. Bob Dylan made a big impression. Jimi Hendrix? Duane Allman? Leo Nocentelli from The Meters? Eric Clapton from Cream?’

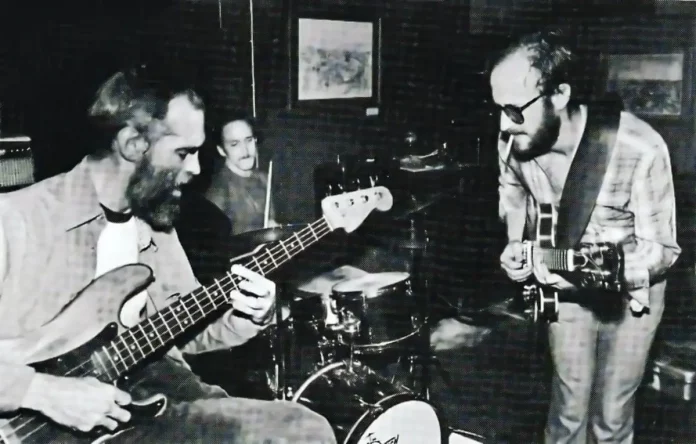

Light years ago, about the time Neil Armstrong snorted a few lines of moon powder, Scofield was a young lion himself. What is the defining difference between the cub and the seasoned veteran?

“I’m pretty much the same guy. But there’s one big difference. I have more confidence now, feel more at ease. To tell you the truth, I wasn’t so confident when I was younger. Not just as a journeyman, but also when I was making a name for myself in the 70s. I don’t think that I was playing that well. These days, my playing is marked by a better use of space. When I began working with Jack DeJohnette, he said that I was standing in his way. I took that as a compliment!”

Striking statements from an artist that gained recognition almost from the word go. The resumé of Scofield, born in Ohio and raised in Connecticut, includes numerous groundbreaking solo albums and cooperations with Charles Mingus, Herbie Hancock, Gerry Mulligan, Joe Henderson, Dave Liebman. Of course, there’s his acclaimed stint with Miles Davis in the early 80s. Since then Scofield has successfully explored the borderland between jazz and roots music with such like-minded buddies as organist Larry Goldings and saxophonist Joe Lovano. He made albums as far apart from one another stylistically as the drum&bass-ish Uberjam and gospel-tinged Piety Street.

“You can still teach me some bebop. I’m a rock guy. I grew up in the late 60s. That’s my point of reference. Bob Dylan made a big impression. Jimi Hendrix? Duane Allman? Leo Nocentelli from The Meters? Eric Clapton from Cream? Definitely! I was present at Cream’s first performance in the United States on the Murray The K. Show. Stunning! However, I didn’t consciously imitate. I think the music of that period permeated a personality that was already going in different directions at once”.

Scofield has pioneered a style that alternates between lurid rock or funk clusters and a fiery dose of free playing. So how does he account for his harmonically advanced and unusually timed ‘out’ playing?

Rock is the offspring of blues. Scofield’s indelible manner of bending notes and his fat, edgy twang seems similar to the style of masters like Albert King.

“Yes, indeed. B.B. King too. But you can take it one step further back in time to country blues. Country blues is like 12-tone music in a way. The sounds these artists made, like Son House, Blind Blake, Skip James and virtually every unknown bluesman, resemble eastern music. Like the Indian raga! Simultaneously, the great innovators Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian bended notes. They had to do it the hard way, with rough strings, but it was audible. To be sure, country music has a twang. Black and white music is more homogeneous than is generally assumed. I think I am subconsciously reaching for that whole vibe. I’m a guitar player. I can’t phrase like a saxophonist. Those guys have it made. So I have to look for other ways”.

Scofield has pioneered a style that alternates swiftly between lurid rock or funk clusters and a fiery dose of free playing, more often than not during the course of one solo. So how does he account for his harmonically advanced and unusually timed “out” playing?

“Well, I can tell you it’s not just playing scales. From a young age, I was crazy about Thelonious Monk, McCoy Tyner, John Coltrane. You can write out what they did, but it’s the way they intuitively played ‘out’ that influenced my conception. The absolutely inspired stuff that they invented on the spot! I studied a lot of Monk and Coltrane. In the early 70s I joined drummer Billy Cobham and keyboardist George Duke’s group. We played the big festivals with Weather Report and John McLaughlin. That was hard funk fusion with a lot of ‘out’ stuff! I just dived into that affair headlong. That really got my career under way”.

His crunchy yet calm voice underlines the kind of modesty and self-knowledge one wishes could be beamed into the souls of all contestants, young and old, of The X Factor

Scofield has always been a prolific writer. The way the maverick American guitarist reflects on this matter is typical of his personality. Glassy eyes and a sympathetic smile complement his easygoing demeanour. His crunchy yet calm voice underlines the kind of modesty and self-knowledge one wishes could be beamed into the souls of all contestants, young and old, of The X Factor. Scofield has The H Factor. A huggable fellow.

“I’m not Bartok. I always look for original lines and interesting rhythm, material that is inviting for my colleagues. They inspire me too. I feel great kinship with Steve Swallow. Like Jack DeJohnette, he’s been a great mentor. Swallow was the first that pushed me to write tunes, as early as the early 70s. He still asks me to deliver! I hear him calling me now, Hey, Sco, you got a tune? He said that writing your own compositions is what a musician needs to do to make your own mark, be someone, create a canvas. He was right”.

Scofield’s Combo 66 is a brand-new canvas. It’s marketed as more straightforward “Sco”, but the colours definitely refuse to stay within the lines. It is comprised of original tunes that are added to the already considerable book of music that Scofield uses on his recent tour. Performing live is yet another, perhaps the most important, aspect of the jazz life. The politically incorrect country artist and whodunit writer Kinky Friedman once said: “Sometimes when you’re performing, your thoughts can travel elsewhere with an almost brilliant clarity. In fact, if the audience ever found out what most entertainers are thinking while emoting on stage, they’d demand their money back”. Is there a semblance of truth in Friedman’s words?

“The Texas Jewboy! Yes, your mind can travel elsewhere, even to ordinary things like the stereotypical groceries. But I’m mostly concentrating, focusing on the notes and listening to the other musicians. Perhaps more than in the studio, playing live is a conversation. It’s a strange phenomenon. As if you’re there but in an entirely different place as well. It’s like being in a zone between the gutter and the stars. You understand? It may not be Kinky, but it’ll do”.