Blogger, biographer, museum archivist and lecturer Ricky Riccardi embodies the American Dream. His dream? To study, to preserve, and to present the legacy of Louis Armstrong and to make his living doing it. Captivated by Pops’ sound and sheer personal magnetism when he first heard him at age 15, Riccardi listened hard and learned everything he could about the great man. Upon earning a master’s in jazz history from Rutgers University in 2005, he married and began working full-time in the family’s house-painting business. Despite dogged efforts to spark interest in his Armstrong research, nothing much happened for a couple years.

The “big bang” came after he started an Armstrong blog in 2007 that began to attract attention. Since then, he has gone from hard-working house painter to world-renowned Armstrong scholar with numerous projects promoting Pops, and a plum position as director of research collections at the Armstrong House Museum in New York. He has also published two marvellous books on his hero. The first, What A Wonderful World, The Magic Of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years (Pantheon Books 2011), aimed to reassess Pops’ music and career beginning with the formation of the All-Stars in 1947.

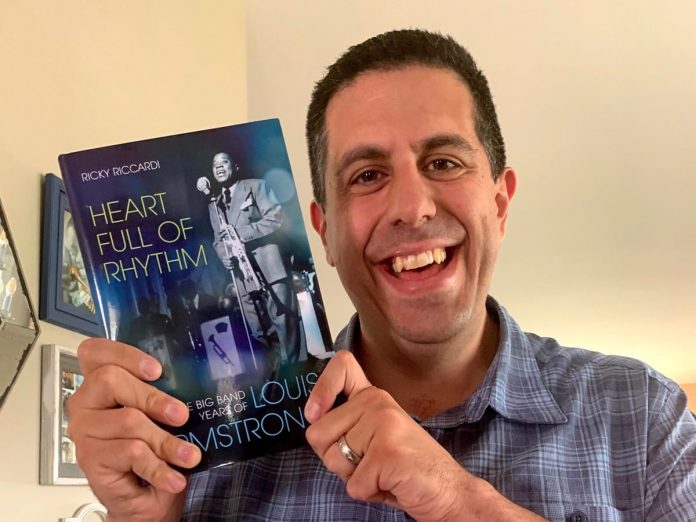

Mr. Riccardi’s new book, Heart Full Of Rhythm, The Big Band Years Of Louis Armstrong (Oxford University Press), adds to the growing body of Armstrong scholarship. Meticulously researched and relying less on previous biographies than original source materials – many of which Riccardi has been able to access through his position at the House Museum – Heart Full Of Rhythm tells the story of the critically neglected and often maligned middle years of 1929-1947. In this period before the All-Stars, the trumpeter experimented with commercial big bands, entrusting his business affairs to a series of colourful managers, finally settling on Joe Glaser who would represent him for many years to come.

Riccardi explores all of this, along with Armstrong’s marriages, his bravura displays of trumpet virtuosity (blasting 100 or more high Cs in succession) that displeased the critics and periodically ruined his lip, his triumphs and failures on Broadway and on screen, his lifelong love affair with marijuana, and the unspeakable racial indignities he and his fellow black musicians suffered. Superb storytelling is enhanced by some 40 photographs, many from Armstrong’s own collection and previously unpublished. These also tell stories. One notable shot depicts members of the band urinating on the side of their bus while touring the south where basic amenities like toilets were often denied black travellers.

At the heart of the book, of course, is the wonderful music Louis made, both live and on wax. Despite critical disapproval in Armstrong’s time and beyond, Riccardi makes a strong case for the merits of this music. To illustrate, he offers detailed yet readable analyses of key records from the later Okehs (1929-1932), the RCA Victors (1932-1933 & 1946-1947), and the Deccas (1935-1946) that stylistically ranged all over the musical map. While he does not sugarcoat accounts of the inferior bands Pops occasionally fronted, his enthusiasm for the best among these records sent me back to my shelves time and again as I read. Riccardi’s insights invariably illuminated the record in question.

Heart Full Of Rhythm elucidates and entertains from start to finish. Each chapter ends with a tantalising hook that anticipates the next, keeping the reader engaged and focused. Like its subject, it swings! In an email exchange with Ricky, the author spoke of his book and other Armstrong-related activities. Here are highlights.

What made you aware of the case for a reassessment of Armstrong’s middle and later years?

Well, for me, the later years always came first and foremost because that was the music that changed my life, especially the Columbia recordings of the 1950s produced by George Avakian. I began reading about Armstrong and frequently encountered the narrative of Louis, the great genius up to 1928 who then made a conscious decision to “go commercial” and become a clown and an Uncle Tom, humiliating himself onstage, playing the same songs every night, recording trifles, etc. I didn’t buy that for a minute.

I should mention that I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Reading Dan Morgenstern’s liner notes and Gary Giddins’s Satchmo were crucial experiences for me and served as a template for what I eventually wanted to write and research. But in 1997, two years into my Armstrong love, Laurence Bergreen published the massive Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life, which spent 424 pages on Armstrong’s life from 1901 to 1943, and then 70 pages on 1944-1971. That was the moment I said to myself “A book! I need to write a book! People are glossing over an incredible part of the story.”

I like to say I began writing that book that day in 1997 and didn’t finish until What A Wonderful World: The Magic Of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years came out in 2011. Honestly, I thought that was the only book I had in me but in the course of meeting musicians and giving presentations around the world, I made a mind-blowing discovery: everyone is on the same page with Armstrong up to 1928, the “young genius”, and now post-1947 Armstrong is more respected than in the past – but it seemed like just about everyone glossed over the middle years. They were just kind of sloughed off.

One of the themes in your book is that Pops had an enormous impact on popular culture and life beyond the immediate musical influence.

I come from a jazz background, have a master’s in jazz history and research and am a bit of a half-assed jazz pianist. And the jazz world really just wants to talk about the notes. That’s why everyone’s in unison agreement with pre-1928 Armstrong, because they can point to a perfectly constructed solo like Potato Head Blues or the dazzling cadenza on West End Blues, transcribe it, analyse it, illustrate how it paved the way for bebop, etc. They also see those 1920s works as some sort of sacred art, untainted by commercial considerations (that’s wrong, but will be tackled in my next book on the early years!).

But Louis Armstrong is so much more than the notes. So I spend a lot of time in Heart Full Of Rhythm talking about comedy, about his film appearances, about his breakthroughs on radio, his popularising of slang, his infuriating experiences with racism, etc. And I feel like those are the things that many in jazz world either don’t pay attention to or they’re embarrassed by. They scratch their heads and wonder why he recorded love songs (because he was, at heart, a romantic) or why he indulged in showmanship (because he truly was funny). Things like that that are turned into flimsy evidence of some sort of decline. But as I try to make the case, Armstrong became a multimedia superstar in the 1930s, beloved by white and black audiences. His slang was adopted by musicians, dozens of songs he recorded immediately entered the Great American Songbook, he broke down barriers to host a sponsored radio show and was often the only featured African American actor in these otherwise white Hollywood films.