In the mid-70s Melody Maker critic Chris Welch described fusion quintet Swift as “an extraordinarily powerful instrumental band somewhat in the mould of Weather Report and the Mahavishnu Orchestra”. Sadly, however, the power of the press was on this occasion not powerful enough and, without ever having released a record, the London-based band fizzled out in 1979, leaving scarcely a trace and being soon forgotten by almost everyone.

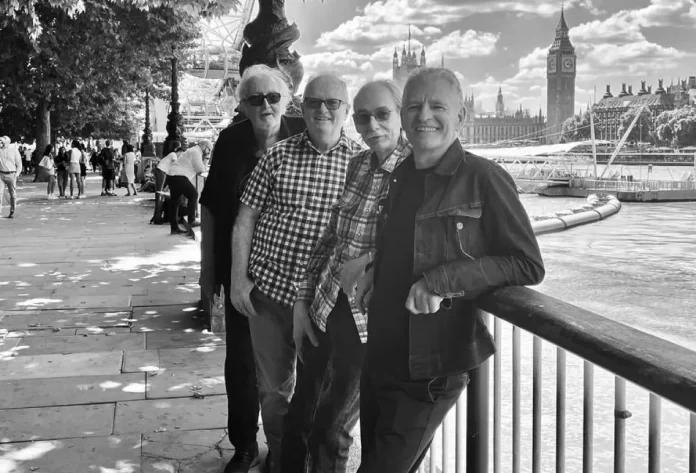

And there the Swift story should end. Except that in 2020 Northern Irish trumpeter Linley Hamilton heard some ancient demos by the band. Blown away, he began playing them on his BBC Radio Ulster programme Jazz World. A buzz developed about the band such that four original members – Welsh keyboard player Hugh John, and, from Northern Ireland, guitarist Larry Dundas, bassist John McCullough and drummer Brendan O’Neill – reconvened and have now released an album, In Another Lifetime, comprising new interpretations of material from the original band’s repertoire. The band have thus managed to pull off the unusual feat of releasing their debut album (available to test drive or buy as download or CD on Bandcamp) 43 years after they split up.

The constraints of the Covid-19 pandemic made it a challenge for musicians who hadn’t collaborated for decades to work together effectively. But guitarist Larry Dundas’s technical wizardry enabled the band to develop a method of recording with the individual musicians using home recording facilities of varying degrees of sophistication.

“After Swift I built up a home studio and I’ve kept that going and when computers came along I very much got into writing and arranging and composing and recording on computer,” explains Dundas. “It was just for personal satisfaction, because I love music. I never thought of it as a career but the skills I built up doing that over the years made it possible to make the Swift album.”

O’Neill describes the band’s modus operandi: “We’d decide the song we wanted to do and have discussions on Zoom. Then from these discussions Larry would make a template of what we liked, with all the parts on computer instruments. Then I would get the template with the computer drums removed and I would then play. Once I’d got a satisfactory drum track the template with my drums on it went to John [with the computer-recorded bass removed] who added bass and it went round like that.”

The band’s biggest triumph was winning the Greater London Arts Association Young Jazz Musicians Of The Year Award in 1977. ‘There were eight bands competing at the Shaw Theatre on Euston Road. One of the judges was Ian Carr’

The musicians acknowledge that the band’s playing has changed. “We were young men in those days,” chuckles John, “with all the pluses and minuses that go with that!”

Continues Dundas: “It was the madness of youth. We just used to throw ourselves into very complicated time signatures at breakneck speed. We’re a lot older now and more conservative!”

McCullough illustrates how the band’s playing has developed with reference to his bass solos on an early demo, Stud, and on Bobok from In Another Lifetime. “Stud’s a crazy 11/8 tune that goes into 13 and it’s going 90 miles an hour and by the time the bass solo comes around I’m flying off the edge of the pier and not slowing down until it’s all over. But Bobok’s a slower, atmospheric tune and I played melodically all through the solo, in sympathy with the mood of the tune. So the band is just more mature.”

There are four original compositions on the album, all by John. “He doesn’t sound like anybody else,” enthuses O’Neill. “His background is very classical and his father was a vicar so he grew up with church music and of course jazz and he’s also a massive fan of people like Bob Dylan and Tom Waits so there’s an incredible mixture of influences.”

McCullough also notes John’s eclecticism: “The Long March has more of a modern jazz feel and it’s very composed with intricate parts; on the opening chords of Bobok there’s almost like a Chick Corea, early Return To Forever feel; This Night [sung by O’Neill] has a Tony Williams influence and is strange and very atmospheric; and Makes A Prison [also sung by O’Neill] is more rock than jazz and there’s a bit of blues in there. So he draws on diverse influences.”

Dundas further praises John’s originality: “A normal jazz group would probably just play the head and then solo, solo, repeat the head and finish. But Hugh’s compositions tell a story. They take you on a journey and don’t necessarily come back to where they started. A lot of them are mini-suites, really.”

There are also interpretations of Thelonious Monk’s Rhythm-A-Ning and the Miles Davis-associated tracks Freedom Jazz Dance (the Eddie Harris composition which was included on the 1966 Miles Smiles), Wayne Shorter’s Paraphernalia (Miles In The Sky, 1968) and Hermeto Pascoal’s Nem Um Talvez (Live-Evil, 1971). “Miles Davis’s electric band was definitely a massive influence for us,” says Dundas. “That band with sometimes John McLaughlin, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul . . . those guys were massive influences on the Swift men so it seemed like if we were going to cover someone’s tunes it should be Miles’s. But we tried to make them different and put our own stamp on them.”

The original Swift had, firstly, John Sanderson and then Pete Thomas playing sax. Neither is involved in the reunion. Instead the band is augmented by English saxophonist and harmonica player Frank Mead and Irish saxophonists Michael Buckley and Derek O’Connor and trumpeter Linley Hamilton. “All absolutely top-notch players,” declares O’Neill. “We couldn’t have dreamed of having quality like that on the album and we’re chuffed they felt it was valid to work on.”

“All of them are just brilliant,” adds Dundas. “The soloing was fantastic. We’re so pleased and amazed that they would give up their time to contribute to our project.”

Swift remain grateful to Chris Welch who so boosted the original band. “He was a fantastic champion of Swift,” says O’Neill. “We didn’t assume we were any great shakes, we really didn’t, so for someone like Chris Welch to write about us was just extraordinary.”

McCullough recalls that Welch first heard the band when they entered the Melody Maker-sponsored 1976 National Rock Folk competition. “We reached the final at the Roundhouse. We played our socks off, the music was really flying, there was a big drum solo, bass solo, everything and we got a rousing reception from the audience. But they awarded the prize to a prog band called Stallion. So we didn’t win but Chris Welch came up and said ‘Wow, what a band!’ and he came to a few gigs and we got a feature in Melody Maker.”

The band’s biggest triumph, however, was winning the Greater London Arts Association Young Jazz Musicians Of The Year Award in 1977. “There were eight bands competing at the Shaw Theatre on Euston Road,” says John. “One of the judges was Ian Carr. And I think the reason we got the award was there were some very good individual players in other bands but they weren’t really bands. They were like a put-together collection of musicians, you didn’t feel there was as much cohesion as with us.”

McCullough explains the prize: “They said, ‘What would be your standard fee for a performance?’ We said ‘£100.’ So if we played the King’s Head in Islington, where we had a residency, and they paid us £15, the GLAA would send us a cheque for £85. Or if we played a students’ union and got £85, the GLAA would send us £15. It was a total game changer. Everybody was holding down jobs: I’d leave work at five o’clock, take a train to somewhere like Nottingham for a gig, sleep on someone’s floor and then go straight to work the next day. But now with £100 coming in for every gig we gave up our day jobs and it was possible to just about scrape by. I would get up in the morning and say to myself ‘Right, I’m a professional musician now.’ I’d listen religiously to music over breakfast; I’d maybe do some classical work on the double bass with my bowing; then some bass guitar, maybe going through stuff Swift were doing or trying to improve by doing exercises from various books. I’d do four hours like that. Then maybe a rehearsal or a gig that night. It was great, being young and able to play the music you wanted.”

One of the band’s career highlights came in 1978 when they supported John McLaughlin with the One Truth Band at the Rainbow Theatre in London. But surely to support one of their heroes and such a legend in a large theatre like the Rainbow must have been terrifying – particularly for guitarist Larry Dundas? “Absolutely daunting!” he agrees. “When I walked on stage and looked at the audience I thought ‘All of this audience have come to see John McLaughlin play guitar and here am I in front of them!’ I was horrified and very, very nervous. But we got through it and they clapped.”

‘We’d thought the McLaughlin gig would open a few more doors but it didn’t. And things were changing. Punk was in full flight then and unfortunately things just faded away’

By now, however, particularly with the GLAA sponsorship having ended, it was becoming clear that Swift weren’t going to crack the big time. “The writing was on the wall,” sighs O’Neill. “There’s only so far you can go with passion, driving up and down the country hawking a Hammond organ and Leslie and all the gear. I think we were road weary at that point. We’d thought the McLaughlin gig would open a few more doors but it didn’t. And things were changing. Punk was in full flight then and unfortunately things just faded away.”

Dundas has a similar take on the band’s demise. “Punk came along just as we were hitting our peak and a lot of the venues we played went punk and weren’t interested in instrumental jazz bands anymore. We did make demos but then you had the winter of discontent so record companies didn’t have as much money to invest. The gigs dried up and the money dried up. A single guy could survive on very little and try and keep the thing going but a few of the band were married and had children and they had to make a living. So various members went off and had careers.”

Indeed, McCullough subsequently worked in international development, in Egypt and Nigeria and elsewhere, continuing to play jazz part-time wherever he was based. He has also recently published a thriller set in Nigeria, The Virtuous Killer. John worked in ICT in music education and as a security guard. Dundas, as we’ve heard, mastered studio techniques. And O’Neill maintained a career as a pro musician, most notably playing with Irish blues-rocker Rory Gallagher for 10 years. Currently he works with Slim Chance, a band dedicated to keeping alive the music of rock star Ronnie Lane, and various other bands.

The future of the rejuvenated Swift is uncertain. “The idea of gigs isn’t really a goer because two of the band haven’t been well but we’re making plans for more recordings” says O’Neill.

John concurs: “I don’t sense a huge enthusiasm for gigging. And anyway there’re nowhere near as many venues now for jazz-rock gigs.”

McCullough is less sure about the band’s prospects: “We spent two years on the album and it was a great story, a band that hadn’t played for 40 years being rediscovered and getting back together and producing an album. But a second album is less of a story, especially if we don’t gig. So I’m not sure about another album.”

Dundas begs to differ: “We all enjoy the process and if we can get enough material we’ll definitely make another album. It may not be soon but eventually it will happen.”