Louis Armstrong is a hero, the great founding genius of jazz. Not much to argue about there. But try seeking a simple explanation of what exactly it was that made him a hero and you will soon find yourself faced by disagreement and controversy. Two serious authors of our own time who have entered the fray are Thomas Brothers, a professor of music, with his magisterial Louis Armstrong: Master Of Modernism, and Ricky Riccardi with, first, What A Wonderful World: The Magic Of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years, and now this volume covering the years from 1929 to 1947. He has one unique advantage, namely that his post as director of research collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum means that he lives and works daily amidst the possessions of a man who seems never to have thrown anything away. Louis Armstrong was a meticulous collector of his own archive – records, photographs, letters (including copies of his own), tape-recorded conversations, acetates of long-forgotten broadcasts. All these are at Riccardi’s disposal, and the use he makes of them is both apposite and endlessly fascinating.

In 23 strictly chronological chapters, each dealing with a period ranging from one month to just under two years, the book follows Armstrong’s progress from the moment when his records began appearing not only in the “Race” lists, but in the “Popular” ones, too, until the end of his big band and the advent of the All Stars. The outline of the story has been told many times: the managers, in particular his remarkable relationship with Joe Glaser, the run-ins with gangsters, the recurrent problems with his lip, his open-handedness with money, his fallings in and out of love. Amidst all that comes the music – not changing with the times so much as showing the times which way to go next. Ricky Riccardi has a masterly touch when it comes to keeping everything in focus, disentangling knotty situations and arriving at brilliantly straightforward conclusions.

Here’s an example. The first stirrings of jazz revivalism occurred in the US in 1939, leading to new records by Jelly Roll Morton, Muggsy Spanier and Sidney Bechet. Decca set up a session reuniting Armstrong and Bechet which produced four good numbers, despite the fact that the two had always been wary of one another, to say the least. Armstrong said he’d enjoyed playing some “good ol’ good ones”, like Down In Honky-Tonk Town. But new records of old music was one thing, reissues of old recorded material was something else. Soon early records that we now know as classics were coming out in cheap editions; in Armstrong’s case it began with an album of 78rpm discs entitled King Louis. From the revivalist point of view, this was Louis at his very peak, the real Louis, whereas the real real Louis was still in business. Thus, says Riccardi, the jazz revival “put the Louis Armstrong of 1940 in direct competition with the Louis Armstrong of the 1920s”, a state of affairs which persisted for the rest of this life.

This was at the root of the aforesaid disagreement and controversy, much of it anyway, according to Riccardi. The body of critics, commentators and fans, the “jazz world” as he calls it, developed its own narrative, an imaginary notion of its ideal Louis that was entirely false. This character was variously portrayed as a musical genius led astray by his own popularity, a black genius ruined by the wiles of the white entertainment industry, a simple-minded genius in thrall to a wicked master called Glaser, and so on. It was all nonsense of course, but, concludes Riccardi, it didn’t matter because “Armstrong was bigger than jazz”. It’s certainly true that there are plenty of what Gunther Schuller sternly called “non-jazz elements” in Armstrong recordings through the 1930s and beyond.

His first “big band” (only a nine-piece actually) had three saxophones (two altos and a tenor), playing in a style unashamedly modelled on that of Guy Lombardo. Armstrong admired Lombardo for the clarity his band achieved in playing a straight melody. Around the same time there was Song Of The Islands, with violins and real Hawaiian voices, and Lonesome Road, featuring Armstrong’s comic “Reverend Satchelmouth” routine. It should have been obvious, even from that early stage, that attempts to confine Louis Armstrong within the single persona of a jazz musician were futile.

Far from being outrageous, “bigger than jazz” seems a perfectly sensible observation as Riccardi piles up the evidence of Armstrong’s popular status in these years. In 1937 alone he became the first African American entertainer to front a sponsored show, the Fleischman Yeast Show, on network radio (NBC), appeared prominently in a Hollywood film (Artists And Models), and beat Benny Goodman’s record for ticket sales at New York’s Paramount theatre. Curiously enough, none of these feats were mentioned in Downbeat, which, according to Riccardi, consistently downplayed black artists during the swing era. As for alienating potential black audiences with his comedy routines, he had them rolling in the aisles with his send-ups of the old stereotypes: spontaneous, subtle and in complete harmony with the spirit of the occasion. That’s how great comedians work. There’s an interesting snippet from one of his taped conversations, talking about his scene with a stolen chicken in Pennies From Heaven (1936): “You can’t do scenes like that now in movies, because of the NAACP. Oh Lord! That was the biggest laugh in the picture!”

One could go on picking out illuminating bits from the riches of this book. There’s the huge matter of his singing, for instance, and its importance in defining what is now called the Great American Song Book. Wherever you look in the culture of the 20th century, he’s likely to be there, somewhere. Yes, he was bigger than jazz, but Ricky Riccardi is always ready to get down to minutiae, such as comparing two takes of the same number and settling on which has the better Armstrong solo. I’d say that was looking after the jazz side of things pretty well.

It is rumoured that the author is investigating Armstrong’s early life and career, with a view to completing a three-volume biography in reverse order. If this excellent book and its predecessor are anything to go by, let’s hope he gets started immediately, if not sooner.

Read Randy L. Smith’s interview with Armstrong author Ricky Riccardi

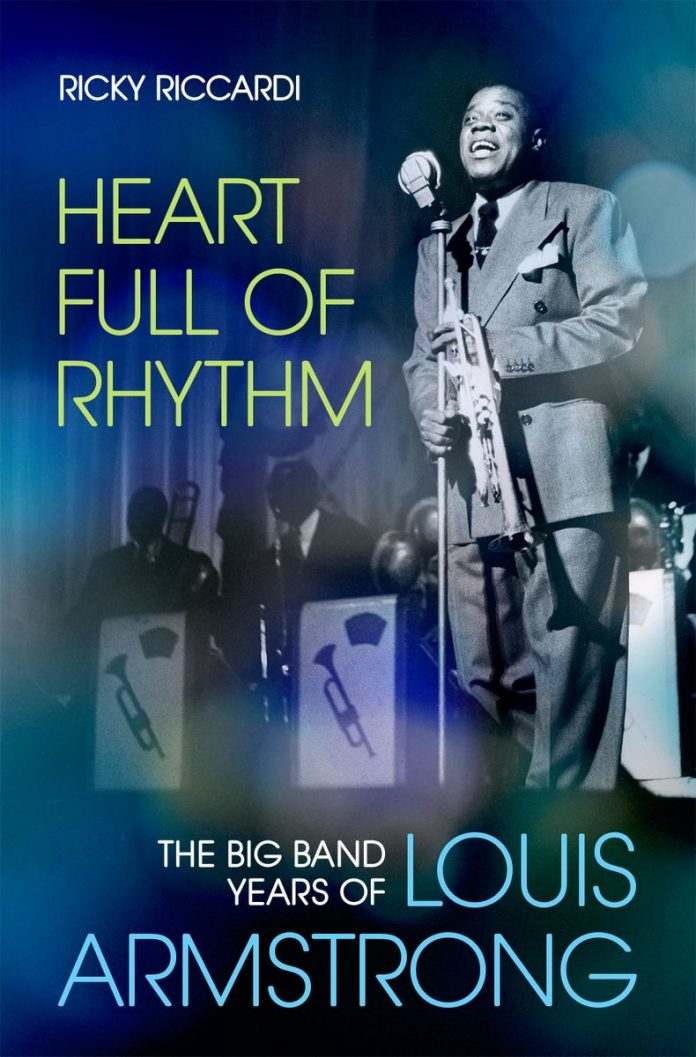

Heart Full Of Rhythm – The Big Band Years Of Louis Armstrong by Ricky Riccardi. Oxford University Press, hb, 414pp, 34 b/w photos, notes, index. £26.99. ISBN 9780190914110. Also available as eBook