Who was the “real” leader of the Art Ensemble of Chicago? As missing-the-point questions go, it’s a good one. Lester Bowie’s “is there a doctor in the house?” schtick made him the most obviously charismatic member. You might cast Roscoe Mitchell as The Composer, until you scan the albums and find that the credits were a lot more democratic. Don Moye, the latecomer, may have completed the line-up, but he was never an engine-room drummer. Malachi Favors was a spirit-presence, often dark and troubling, but he followed as well as led. What we can say without strain is that Joseph Jarman was the group’s intellectual and poet, possessed of a mind that saw music as a continuum activity that aligned with language and the movements of the physical body, also with our place in the world.

When he introduced his writings in 1977, he defined exile as “a state of mind that people get into in order to escape from the reality of themselves in the world of the now”, but insisted that it was a state from which it was always possible to return. Much of his music, and his writing, was concerned with that process of restoration. Jarman had included text (recited by Sherri Scott) in his early Delmark recording As If It Were The Seasons, but probably the only well-known text is Non-Cognitive Aspects Of The City, of which Mitchell’s setting became a key component of the AEC repertoire.

Jarman recognised that the Black Arts Movement rested as much on personal testimony as on poetry; Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington were as prominent in its ancestry as Langston Hughes or Paul Laurence Dunbar. The “up from slavery” narrative developed into a long, sometimes pained examination of “who am I in this society?” and what Jarman called exile was an understandable failure to confront that question day by day, minute by minute. Easier to pretend, he told me once, that the oppressive world simply didn’t exist. Martial arts, of which he became a master, combine physical opposition with corporal poetry, and that is what drew him to them, aikido in particular. In an astonishing text headed (combat) he writes: “If we train (trane) for / reality; we must fix ourselves / for the event. We are one / with the universe, / so –“. What follows is his attempt to clarify the spiritual returns of physical training.

There are other, perhaps more familiar texts and sentiments: “PEOPLE IN SORROW // offered her up to great nothing / being energy the song the song / song to bring joy to give / light all clear vision power / what we are OM the people”. Again, the syntax, punctuation and distribution of space is non-standard, but not non-cognitive, for the hesitations and repetitions are the urgent ticker of a mind writing exactly as it is thinking.

There’s a tendency to think that the internet changed everything and that blogging is a new and perilously unedited form of communication, leading inexorably to ever more extreme positions, trolling and from there, actual violence. What everyone forgets is that all creative people blogged in the 60 and 70s. Poets made and circulated their own work, in hand-crafted chapbooks, stitched together collections of verse, cards and posters, most of which proved to be as ephemeral as a present-day internet statement. What Jarman did, in its unmediated, unedited, frequently “ungrammatical” way, was to present a stream of consciousness that led, yes, to violence but to a violence that had been codified and controlled to the point where it became beautiful.

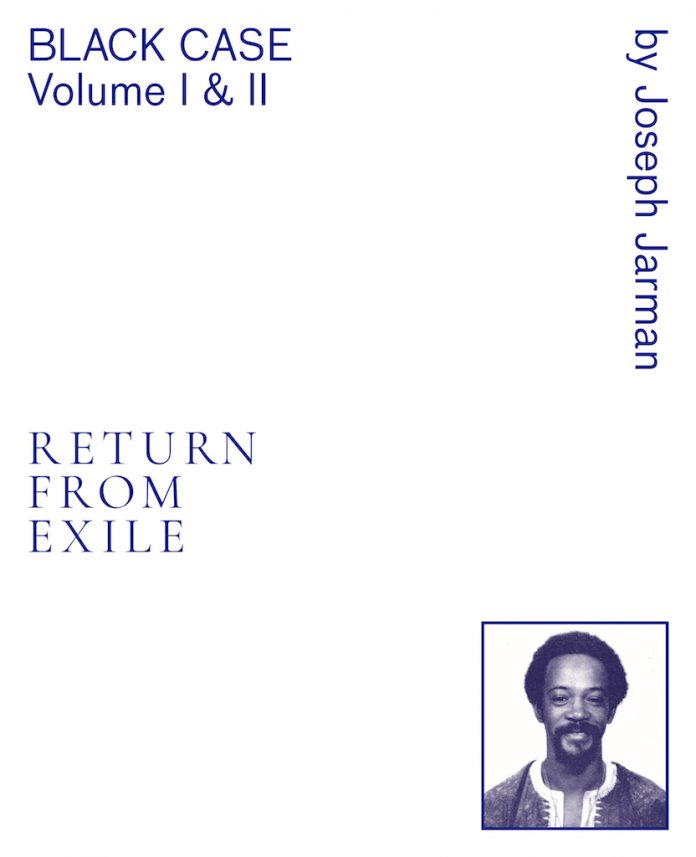

The uncaptioned photographs in the book – reproduced in a faded blue – are all moments of stilled action: two men, unidentifiable, carrying large fish along a city street; Jarman (is it?) in African clothes and short dreads with a flute across his knees and a wistful expression; George Jackson smiling sweetly before Soledad cut him down.

Return From Exile is not a text that can readily be analysed. It is neither poetry, and therefore called on to obey (some of) the rules of poetics; nor is it autobiography, which demands some coherence of chronology; nor set of scores, though some are reproduced; nor is it a conventional spiritual manual – instead it enacts what it insists: that there is a return available for all of us, that coming through the discipline of combat there is a profound peace, that music tunes us to the “reality” that surrounds us. What impresses me about Jarman – writing, music and self – is how un-utopian it is, in the sense that it promises nothing but effort, steady spiritual and musical practice, training and work. The idea that expression will ever be “free”, in the sense of unearned, simply doesn’t occur to him.

A great book, but not a comfortable read. Turning its pages is like following the movements of a fifth dan in the dojo, movements you can only approximate stiffly. With effort, though, you can get there. And as he said, all music is practice, too, and nothing but practice.

Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile, by Joseph Jarman (with introduction by Brent Hayes Edwards; foreword by Thulani Edwards). Blank Forms Editions