An extraordinary book by an extraordinary musician – and man – Desperado: An Autobiography is required reading for anyone with a serious interest in European jazz of the past six decades or so. It will also repay close attention from those curious about the psychology of addiction. The helpful cigarettes and wine which enabled a shy Stańko (1942–2018) to conquer his early reticence about performing would metamorphose into an ever-deepening dependence on these substances, mixed with a further addiction to hash, pills and heroin. Stańko evinces what is often a remarkably balanced perspective on all such, but would never come to regret the momentous change that came in 1992, when he finally got the monkey off his back and learned to relish the beauty of a clean and creative life.

Rafal Ksiezyk, a Polish journalist and music critic literate in any number of matters pertaining to Stańko’s life and art, is a lively and empathetic interviewer. The 28 chapters he assembled are arranged chronologically: each follows the same format, where a series of short related questions from Ksiezyk precipitate answers of both tautly focused and more discursive consequence from Stańko. The format is especially apposite for a musician who pondered constantly the nature of the relationship between extended improvisation and dynamically arresting form in jazz.

The book fascinates on a number of levels. For example, those curious to know what life for a Polish jazz musician was like under communism will find some revealing passages. While Stańko laments the fact that the economic “security” of the system meant that “the jerk got paid as much as the genius”, when asked by Ksiezyk if his music had been received differently by the West and the (former) socialist countries, Stańko recalls how, in his early days in Poland playing, e.g., with pianist Krzysztof Komeda, audience enthusiasm was high. “Please remember that, when Cecil Taylor played at [Warsaw’s] Jazz Jamboree in 1965, he got a standing ovation […] Whenever we played with Komeda, we always got an excellent reception, because we were playing music that was modern but also melodic.” (p 30).

The theme of “modern but also melodic” is a leitmotif here, as Stańko traces his development from the “melodic atonalism” and rhythmic urgency of his early, modal and free form days to the ostensibly simplified yet rhythmically supple and subtly heightened lyricism of the 1975 ECM Balladyna with Tomasz Szukalski (ts), Dave Holland (b) and Edward Vesala (d) – and also of further ECM Stańko classics such as Mattka Joanna (1994) and Leosia (1997), Litania: The Music Of Krzysztof Komeda (1997) and From The Green Hill (1999), Soul Of Things (2002) and Lontano (2006).

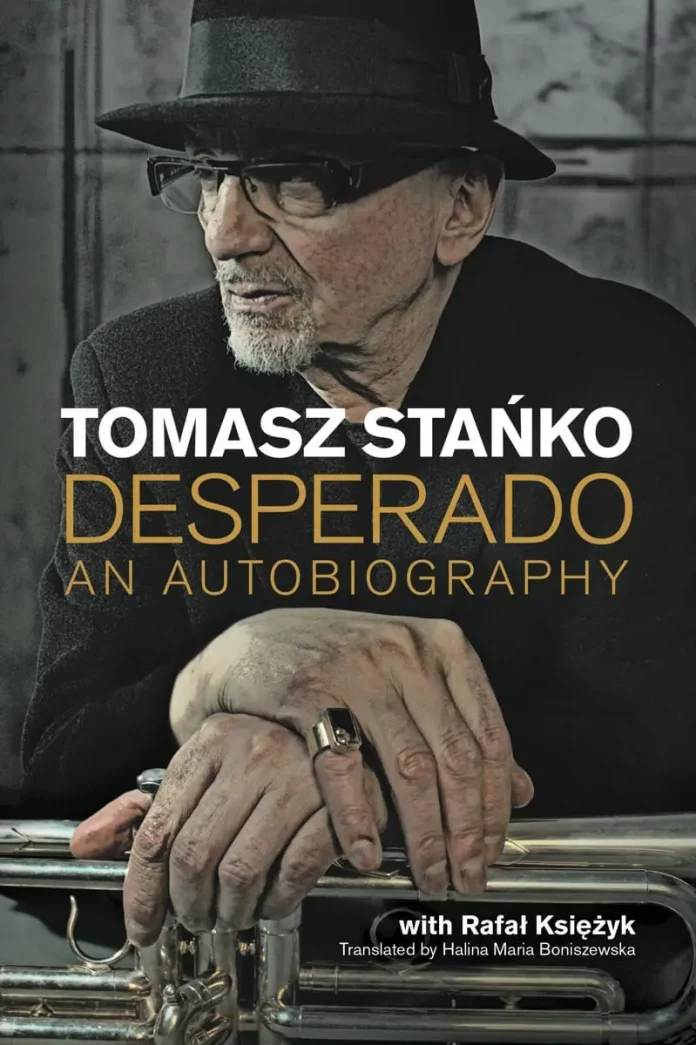

Unfortunately, the main text of Desperado (first published in Polish in 2010) concludes its chronology shortly before the April 2009 recording of Stańko’s Dark Eyes masterpiece. But there are some fine pages on how this project with Alexi Tuomarila (p), Jakob Bro (elg), Anders Christensen (elb) and Olavi Louhivuori (d) evolved in Stańko’s mind. And Desperado‘s excellent cover photo by Andrzej Tyszko is the lead image in the booklet for the album.

Given how important a latter-day album such as Litania was for Stańko’s breakthrough to world-wide recognition, it’s only natural that a fair portion of Desperado focuses on the work with Manfred Eicher for ECM. But there is much, much more to the book. Ksiezyk draws perceptive comments from Stańko on both free and smooth jazz as well as all sorts of musicians with whom he played. These include Roman Dylag and Rune Carlsson, Don Cherry and Jan Garbarek, Bobo Stenson and Edward Vesala; Dave Holland, Arild Andersen and Anders Jormin, Tony Oxley, Cecil Taylor and Marcin Wasilewski. We learn about Stanko’s dismissal of the notion that he plays “folk music” and of his literate appreciation of diverse figures in jazz such as Monk, the Davis/Coltrane quintet, Woody Shaw, The Trio with John Surman, Barre Phillips and Stu Martin, and Jon Hendricks – whose narration on George Russell’s “fabulous” 1958 New York, N.Y. Stańko celebrates as a forerunner of rap. In classical music, Bach, Mahler and Bartok get special mention.

Ksiezyk details many an aspect of Stańko’s richly diversified career, from the early days with Komeda and, e.g., saxophonist Zbigniew Namyslowski through to the various solo concerts which began in 1978 and the 1983 collaboration with the Graham Collier Orchestra. Later highlights of the 1980s and early 1990s included the funky yet meditative Witkacy Peyotl / Freelectronic release, dedicated in substantial part to the legendary Polish polymath Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (commonly known as Witkacy); Stańko’s subsequent participation in Cecil Taylor’s European Orchestra as well as the Jazz Baltica Ensemble, and the aptly titled 1991 Power Bros trio release Bluish with Arild Andersen and Jon Christensen.

Stańko’s work for Polish film and theatre is covered extensively and there is throughout rewarding focus on the diversity of contexts within which the soulfulness of what Stańko called his developed and “dirty” sound could be projected. And due attention is paid to the ups and downs of domestic life. Born in 1978 to Stańko and his wife Joanna Renke, daughter Anna would eventually become Stańko’s manager and now runs the Tomasz Stańko Archive.

Throughout, Stańko comes across as a man of considerable native intelligence, vitality and humour, admixed with that special dark side to his nature which so often infuses his music. He could be unhappy with his (always unmuted) sound which early on was sometimes compared to that of Don Ellis. “Let’s face it,” Stańko says at one point, “I’m a fucked-up cat.” But if such emotional nakedness might be difficult and challenging, Stańko could be as soulful and sensitive as his music (largely) attests. We learn, above all, of his dislike of cold or rigid intellectualism and his preference for depth of tone rather than technique, for feeling, or sensation, over knowledge – for having the courage, in life as in art, to “go with the flow” and “bend” matters when necessary.

Seriously interested in the arts, Stańko rated William Burroughs highly while the title Dark Eyes came from a piece by the Austrian expressionist painter Oskar Kokoshka. As Desperado documents so well, the self-named “Individual Being” that was Tomasz Stańko had an uncanny ability to elucidate key aspects of form and feeling in jazz – in both American and European settings – while also sensing what jazz might mean, or signify, in the wider cultural context(s) of our times.

What one might call a spiritually oriented existentialist, keenly aware of the idea of being “nothing” within the enormity of evolution, yet totally dedicated to yea-saying, to creative affirmation, Stańko was self-critical and searching to the end. The last factor was especially evident when he moved to New York to test himself against and with the contemporary cream of the Big Apple. Hear Wislawa and December Avenue, the 2012 and 2016 ECM albums he made with his New York quartet featuring David Virelles (p), Gerald Cleaver (d) and either Thomas Morgan or Reuben Rogers (b).

One can regret that a supplementary summary was not added to the original 2010 edition, offered here in a most readable translation. But many key details of Stańko’s activities up to his death in Warsaw in July 2018 are included in the concluding biographical time-line and excellent discography. In sum: a stimulating, richly rewarding and absolutely unmissable volume about one of the most distinctive, resolute and resonant poets in jazz.

Tomasz Stańko, Desperado: An Autobiography by Tomasz Stańko with Rafal Ksiezyk (translated by Halina Maria Boniszewska and with a series editor’s preface by Alyn Shipton). Equinox, 356 pp with 43 b&w illustrations, discography, biographical time-line & index, hb, £33.40. ISBN 978 1 80050 222 2