When Dizzy Gillespie heard that Clifford Brown had been killed in a 1956 car accident his shocked reaction became an emotional epitaph: “Jazz was dealt a lethal blow by the death of Clifford Brown … there can be no replacement for his artistry.” At the age of 25 he had become not only one of the finest of all post-war jazz trumpeters but also the co-leader with Max Roach of a quintet that was hugely influential on the emerging hard bop school.

In 1948 he matriculated at Delaware State College where he was known as ‘The Brain’ (maths was his major). In the late 40s he started visiting jazz clubs in Philadelphia; there he met Red Rodney, who told Mark Gardner ‘I saw great promise in him when he was fifteen or sixteen years old. Even then he sounded very much like Fats’

He was born in Wilmington, Delaware on 30 October 1930 into a very close family of eight children who were all encouraged musically by their father. He kept a selection of instruments around the house and when Clifford was about 12 he asked to play the trumpet, apparently taking to it “like a fish to water.” Around this time the family listened to the popular bands of the day on the radio, such as Lionel Hampton, Jimmie Lunceford and Fletcher Henderson. Clifford benefited from lessons with the celebrated Robert Lowery whose other students over the years included Ernie Watts, Lem Winchester and Marcus Belgrave. A private recording of Brownie playing Ornithology in a duet with his teacher around 1949/1950 has survived, representing his earliest recorded solo. “He really knew what he wanted to do … all he needed was the right person and I think I was the one at the time,” Lowery told Phil Schaap.

Brown was already aware of polytonality and Lowery encouraged him to learn the piano, an instrument he eventually became very proficient on. Precociously talented at just about everything, he began a lifelong love of chess in his mid-teens. He also excelled at pool and table-tennis. When he was 15 he attended Howard High School. There he fell under the guidance of Harry Andrews, who taught him from the famous Arban Method for Trumpet. Clifford played in the high school band, marching on the field before football games and also at parades in Wilmington.

In 1948 he matriculated at Delaware State College where he was known as “The Brain” (maths was his major). In the late 40s he started visiting jazz clubs in Philadelphia; there he met Red Rodney, who told Mark Gardner “I saw great promise in him when he was fifteen or sixteen years old. Even then he sounded very much like Fats.” Navarro was certainly an early influence and although there was a seven-year difference in their ages they became close friends.

Dizzy Gillespie was very important too, as was Harry James. In 1956, when Leonard Feather published a poll for musicians to nominate their favourites, Brownie voted for one name on trumpet – Dizzy Gillespie. Billy Root was someone else who was very impressed with the young trumpeter and a few years before he died in Las Vegas he told me “I often played with Clifford and I loved him. I never met a nicer person. He was just superb in every way and after Dizzy he was my favourite. He came in one night when Bird was at the Blue Note and Charlie got him up on the bandstand. Brownie was hiding behind the big upright piano and Bird said ‘Come out front with me man, I don’t want you back there.’” In those early years in Philadelphia he also got to play with John Coles, Benny Golson and Miles Davis at local Elk Lodges.

In 1949 Dizzy Gillespie brought his exciting big band to Wilmington for a booking at the Odd Fellows Temple, which was packed with enthusiasts. Just before curtain-up it became known that Benny Harris could not be found. Robert Lowery, who was in the audience, informed Gillespie that there was a ready-made replacement in the house. Clifford joined the trumpet section for the night and the leader was so impressed he gave him the solo on I Can’t Get Started.

A year later, while travelling to a booking, Brown was involved in a serious car crash. The driver and his girlfriend were killed and Clifford was critically injured. Bones were broken in both legs and the right side of his torso needed a full body cast to reset his frame. He spent several months in hospital and one of his visitors was Dizzy Gillespie. It was a year before he recovered and while hospitalised he received the shocking news that his friend Fats Navarro had died from TB and drug abuse. During a long convalescence he slowly rebuilt his embouchure while doing some local work on piano.

According to Ken Vail’s Bird’s Diary, Charlie Parker was booked at the Club Harlem in Philadelphia in May 1951 when Benny Harris once again was missing in action. Brownie got a call from a friend and took over during Bird’s residency. The following week Harris rejoined the group for Parker’s gig in Buffalo, New York. In November that year fellow Philadelphian Jimmy Heath invited Clifford to join a quintet he had formed with Dolo Coker, Sugie Rhodes and Philly Joe Jones for a job at Spider Kelly’s. On one occasion the tenor man remembered a very drunk woman coming up to the bandstand and saying to the trumpeter “I don’t know what you’re playin’ but you’re playin’ the hell out of it!”

Late in 1951 Brown was in the audience when Chris Powell and the Blue Flames appeared at a Philadelphia dance venue. He was invited to sit-in and impressed the leader so much that he was asked to join the band on a permanent basis. Powell had a popular R&B band and he often featured jazz musicians like Osie Johnson, Jymie Merritt, Jimmy Heath, Jimmy Crawford, Buster Crawford and Philly Joe Jones. Clifford recorded his first commercially released solos on two calypsos with the band in Chicago in March 1952. Ida Red (dedicated to his current girlfriend) finds him in a cup mute and I Come From Jamaica has a confident open statement displaying exemplary control of the upper register.

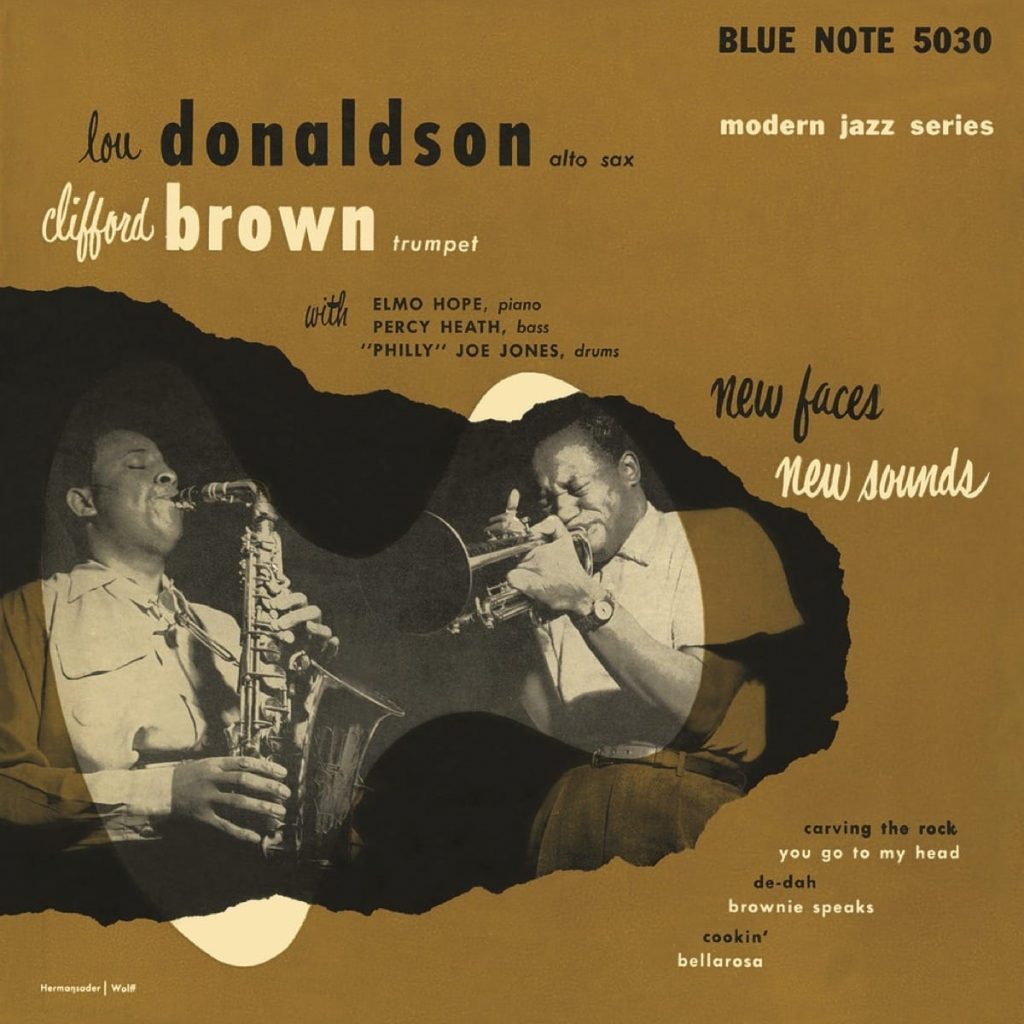

In 1953 Clifford left the Blue Flames to try his luck in New York and in June that year he was selected for a Lou Donaldson Blue Note date. He brought his own tune, Brownie Speaks, to the session and his three choruses on this uptempo original feature some very well-articulated eighth note passages. Two days later he was in the studios again, this time for a Tadd Dameron nonet session for Prestige. The line-up included Idrees Sullieman, Benny Golson, Gigi Gryce and Philly Joe Jones. Philly JJ (based on Woody’n You) is essentially a drum feature but Brown is also heard in a powerful and inventive solo indicating that a new trumpet star had arrived on the New York scene. Later that month he teamed up with J.J. Johnson, who was making a welcome return as a recording artist after a brief retirement. Brown’s outstanding performances here, especially on Capri and Turnpike, convinced Blue Note to award him a recording contract.

As soon as the J.J. session ended Clifford drove down to Atlantic City for a summer residency at the Paradise club with a Dameron group that included Johnny Coles, Cecil Payne, Gigi Gryce, Benny Golson, Percy Heath and Philly Joe Jones. They backed variety acts and also played for dancers and on one occasion Sammy Davis sat in on drums. At the end of the residency Quincy Jones arranged for Brown, Gryce and Golson to join Lionel Hampton’s band. The leader would often have his musicians marching up and down the aisles at Harlem’s Apollo Theatre and elsewhere playing The Saints, Flying Home and Hamp’s Boogie Woogie. Jones called Hampton “the first rock ’n’ roll bandleader” but his showmanship did not go down too well with some of the newer band members, especially Brown and Gryce. Gigi and the trumpeter had similar lifestyles that did not include drinking, smoking or taking drugs. They became very close and Gigi went on to become godfather to Clifford Brown Junior.

Just before the Hampton band took off on a three-month tour of Europe, Clifford made his debut as a leader for the Blue Note label. Gryce contributed Hymn Of The Orient which is taken faster than Stan Getz did it when he introduced it a year earlier. Gigi also provided it with a new A section in the last chorus. Cherokee has him centre stage throughout, clearly delighting in Ray Noble’s sophisticated challenges in the tricky bridge passages. The track concludes with some exciting exchanges with Art Blakey. In contrast, Easy Living finds him at his most romantic and lyrical with a warm, broad sound especially in the lower register.

Read part two of this article; read part three