Following the death of Charlie Watts in 2021 (see the JJ obituary, focused on his jazz connections), Paul Sexton has written about the life, times and career of the late Rolling Stones drummer. Over the past 30 years he has followed the group and interviewed its members and draws on this contact and knowledge along with contributions from Charlie’s family and close friends.

He covers Charlie’s early life, growing up in north-west London with neighbour and lifelong friend bassist Dave Green, playing in R&B bands with Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies and others, then the heady days of the Rolling Stones. Charlie was the group’s lynchpin for 60 years, despite his reluctance and personal misgivings.

Much of the book, understandably, focuses on the Stones’ music and the relentless schedule of touring, but JJ readers will be interested in the sections that cover his first love, jazz. It started out with an interest in Earl Bostic and developed after hearing records by Charlie Parker (with Max Roach) and Chico Hamilton with Gerry Mulligan’s quartet. As a teenager he and Green would visit the 100 Club and both played with local jazz band the Joe Jones Seven.

His love for jazz continued throughout his life, and from the early 80s he spent his time away from the Stones in pursuing this, with his quintet (where Sexton confuses altoist Peter King with Ronnie Scott associate Pete King), tentet and all-star orchestra. I feel the author could have made more of this, given Charlie’s enthusiasm for the music, and more of his work with former Stones pianist Ian Stewart, whose band Rocket 88 included saxophonists Willie Garnett and Olaf Vas. There’s also a spelling mistake with Roy Haynes’ name, which the proof-readers should have picked up, but a minor quibble.

There’s a fair amount of material about Charlie’s collecting – clothes, memorabilia, P.G. Wodehouse books, drum kits – and his generosity and loyalty to friends. This applied to my ex-colleague, the late Ray Smith, of Collet’s (and later Ray’s Jazz Shop) who gets a mention for supplying Charlie with jazz records. It omits to say that when Ray was taken into hospital some years ago, the nurses were amazed to read Charlie’s get-well message on a huge bouquet that arrived. He’d known Ray, a fellow drummer, from Richmond days when the Stones were the support band for Wally Fawkes’ Troglodytes, in which Ray played. On one occasion he borrowed Ray’s kit and put a hole in the snare. Charlie gave Ray a few quid to have it repaired, although this was never done, the money finding its way to the bar and an Elastoplast repair remaining on the drum for years to come.

Charlie’s interest in cricket is briefly mentioned: he would visit Lord’s to watch matches, often with Ray, discussing aspects of the game. After the setting up of Ray’s Jazz Shop, Charlie agreed to be interviewed with Ray in the shop, an item televised on ITN and now on YouTube, which helped raise the shop’s profile, and on the opening night with his orchestra at Ronnie Scott’s he reserved a front table for Ray and the shop staff. Following Ray’s death, he came along to Soho Square and joined a few of us discreetly scatter the ashes. It was this thoughtfulness that Charlie was often remembered for, and other examples are covered in the book.

What comes over in this readable book is that of a sound and dependable drummer, a modest and private man, devoted to his family but with a lasting passion for jazz.

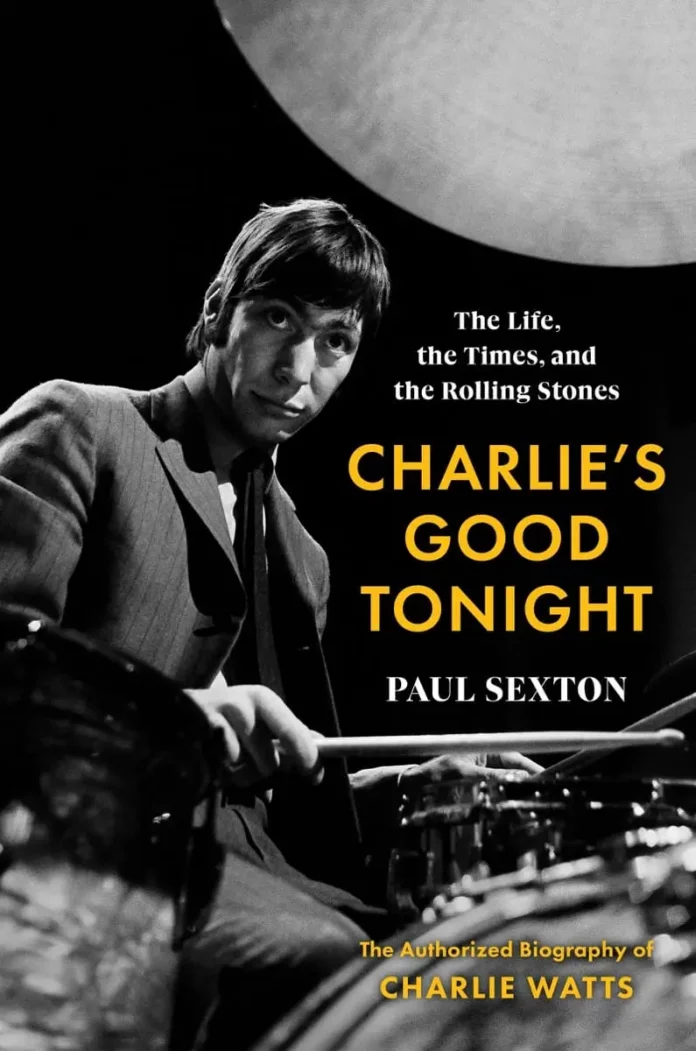

Charlie’s Good Tonight – The Authorized Biography of Charlie Watts, by Paul Sexton. Mudlark/Harper Collins, 344pp with 44 photographs, h/b £25. ISBN 978-0-00-854633-5