Sleeve writer Morgan Ames claims that to get the most from this album the listener must ‘spend a few moments clearing the mind of its musical preconditioning’. Yet it is Davis who makes this impossible. Whatever Ames may think, the trumpeter’s lines are no different from those that have graced his work of the last ten years and the listener’s mind is naturally forced into these already charted territories.

In many ways this was an inevitable direction for Davis’ music to take. The Quintet, with Shorter and Williams, made frequent and brilliant use of an ostinato rhythmic vamp. It was repeated over and over again so that when it was dropped, the audience carried it on in their minds. The repetitive figures of the rock/jazz fusion extend this concept, although this record is probably better than ‘In a Silent Way’ or ‘Bitches Brew’ in that Jarrett has a better grasp of the needs of the music than had Zawinul, Young or McLaughlin. Furthermore, DeJohnette is more incisive here than on ‘Bitches’, a fact that makes stronger its jazz allegiances.

As with all Davis rock albums, much depends on the drummer to ensure that the centreless swirl of the rhythmic tapestry avoids the worst excesses of the underground pop groups. The backing for Davis’ superbly lyrical solo on Thursday is a case in point. Certain rhythmic figures and embellishments of sound are introduced for no reason and with no advantage. The passage would be perfect with only DeJohnette’s driving drums as a spur – a fact underlined by the beautiful and spare opening bars of Friday.

Whatever its short-comings, Davis now seems to be mastering the idiom. His supporters, however, are slow to acknowledge that the rather superficial backgrounds follow closely the path trodden by Charles Lloyd, a man whose work they justly criticize. Interludes like the frantic electronic ending to Thursday or the ludicrous opening of Saturday are both contrived and unexciting. There are also many moments when the textures are cluttered, even if the fact is slightly obscured by DeJohnette’s fiercely swinging drums.

Davis is inevitably superb. This music has captured his imagination and on every title he solos with distinction. The structure of his main solos on Thursday and Friday are similar, although all have a majesty that is timeless. Grossman has yet to learn Davis’ lesson regarding space and he becomes trapped in the snare of filling every inch of his solo space.

There are moments of real inspiration on this record. Davis’ slow second solo on Friday is superb; each idea is self contained yet part of a central idea that is developed with logic. It seems irrelevant to argue what might have been or indeed whether this is progress. In retrospect, I think we may regard this group as the best of the abortive rock/jazz fusion chapter of jazz. Unfortunately it is something of a model by which several young groups are inspired, groups that have neither a gifted horn like Davis or a drumming giant like DeJohnette to transpose a stultifying idiom into meaningful music.

Discography

Wednesday Miles (24¼ min) – Thursday Miles (26½ min) – Friday Miles (27¾ min) – Saturday Miles (22½ min)

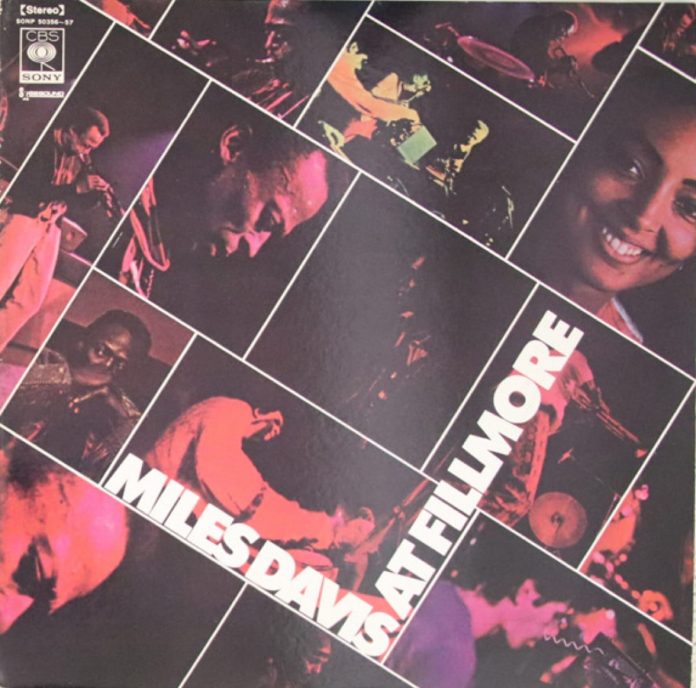

Miles Davis (tpt); Steve Grossman (sop); Keith Jarrett (org); Chick Corea (elec/pno); Dave Holland (bs/bs-gtr); Jack DeJohnette (dm); Airto Moreira (perc).

(CBS 66257 double album £2.99)