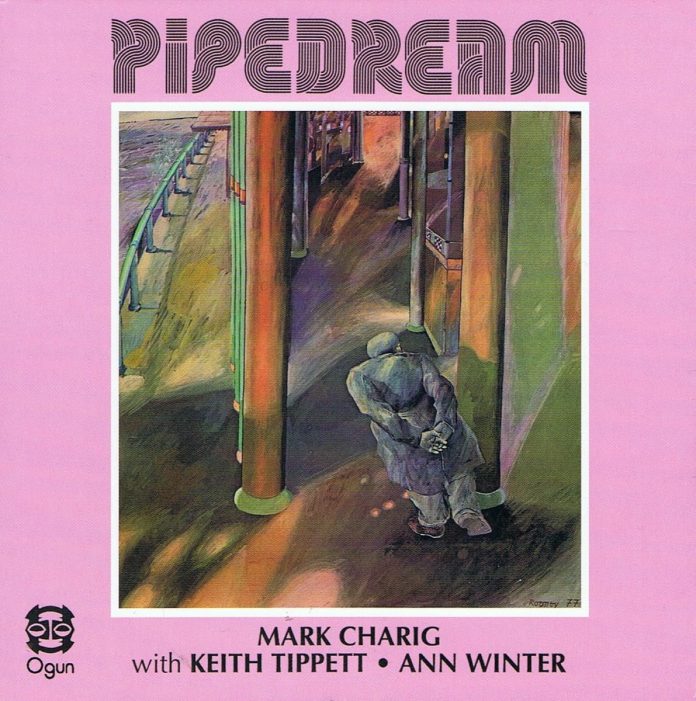

Keith Tippett’s recent passing sent me scurrying back to the percentage of his discography that I have on record; the exercise disclosed facets of his music that had previously escaped me. The trio of Tippett on organ, zither, piano voice and bell, Mark Charig on cornet and tenor horn and Ann Winter on voice and bell recorded the Pipedream album in January 1977, and the Ogun label, that modest concern which documented so much of the vibrant British / South African jazz of the 1970s, put it out under Charig’s name.

Those bare details reveal little of the music’s richness, which with casual listening discloses resemblances with Tippett’s work with Ovary Lodge. Deeper, more focused listening reveals the shortcomings of blithe comparison, however, for this is a set which stands as a unique document in both Tippett’s and Charig’s discography, while as far as I’m aware it captures Ann Winter’s sole appearance on record.

Given the music’s gravity, however, there is in a sense another, ethereal “participant”, in the form of St. Stephen’s Church, Southmead, Bristol, because the acoustics of the space the music was recorded in seem to play an “active” / passive role. Indeed in his original sleeve note Charig refers to how the atmosphere and acoustics suggested the totally improvised music, a turn of phrase which I feel undersells things a little, because for me the album amounts to one of those oddly rare occasions when ample rewards can be drawn as much from the interplay between musicians and the room they’re in as they can from the quiet austerity the music is imbued with.

In music, as in any other field of artistic endeavour, abstraction can peel away preconceived notions, leave a void for the imagination to fill, and while the tolling of the church bell as carried out by both Tippett and Winter notionally marks time, the moments throughout this set, which in many positive ways is something of a discographical anomaly, are commemorated by music so of those moments that it encapsulates Eric Dolphy’s assertion to the effect that once music is over it’s gone, in the air.

The business of recording, despite any misgivings about the pointlessness of trying to capture an ongoing process, of work destined always to remain unfinished, in this case has captured a body of unusually deep resonance.