Shortly after the release of Mantle Piece, Chris Spedding was approached by trumpeter Ian Carr to join jazz/rock combo Nucleus. The band was completed by Karl Jenkins (oboe, saxophone and keyboards), Brian Smith (saxophone and flute), Jeff Clyne (bass) and John Marshall (drums). It soon secured a deal with the embryonic Vertigo label.

Spedding contributed two pieces to Nucleus’s debut album, Elastic Rock. The first was the very brief Striation, co-credited to Clyne. “Striation is one of those short pieces we stuck between the tracks on Elastic Rock as a link. In our live shows we would ‘segue’ one song into another with no gaps between numbers. So that was an attempt to make the record sound more like our live shows. Not sure if that was a good idea, but those pieces were always intended as short, improvised link bits.”

His other contribution was Twisted Track – originally recorded on Mantle Piece – an altogether more muscular instrumental. “I did write the chart for Nucleus’s version of Twisted Track. I thought that track and Karl Jenkins’ title track the most successful Nucleus tracks I played on.”

‘Mike Gibbs was very open to listening to all types of music. I remember going over to his house with armfuls of Motown records which he loved. The only surprising thing was that he seemed unfamiliar with a lot of it. Musicians like Gibbs seemed to be just starting to be aware of a whole world of music outside jazz’

As a result of his continuing contractual liabilities to Harvest, Spedding recorded Backwood Progression (1970) over the course of a week at Abbey Road. The album demonstrates how rapidly his own compositional skills had advanced. His lyrics exploit poetic licence employing subtle rhymes that indicate his appetite for doing different.

Though Andrew King is credited as the album’s producer, it was Spedding who oversaw the bulk of production duties with Peter Bown operating as the main engineer and Alan Parsons assisting. “He was really old school in his approach, and did a great job in getting the sounds sorted out for the album. But when he was sick, then Alan would come in to cover for him.”

The album consists entirely of original material apart from Dylan’s Please Mrs Henry which first surfaced on the Great White Wonder bootleg.

“I was into The Band and Bob Dylan, but was unimpressed by what was becoming known as ‘prog rock’ – Led Zeppelin etc. Hence the rather heavy-handed, punning title, which was meant to hint that to ‘progress’ you need to go ‘back’ to the ‘woods’ – i.e., the country. I was already doing session work by now so the Session Man song was a semi-autobiographical commentary.”

Prior to recording Backwood Progression, Spedding had also guested on the first Jack Bruce album, Songs For A Tailor (1969). “I was still very inexperienced at making records. It was an invaluable opportunity and certainly put my name around the studio scene.” Spedding found his participation in the process somewhat overwhelming, but made several telling contributions including his closing solo on To Isengard.

“Yes, that’s me in my brief Sonny Sharrock, wah-wah, fuzz, bottleneck phase.” He did not always find working in complex time signatures so pleasurable, even if always ready for a challenge. He agreed to guest on Bruce’s third album Harmony Row (1971) but refused to tour with the band to promote the album.

‘I was the only guy in Nucleus, I believe, who was from the rock world. Not many rock guitarists in 1969/70 could fit in easily with musicians coming from jazz.’ Spedding was by this time seeking a simpler, more direct form of music-making far removed from the restrictive attitudes he encountered with the likes of Nucleus

Fusion jazz was very much the flavour of the day, and Spedding soon found himself working with a host of British jazz luminaries including Mike Westbrook on his album Love Songs (1970) and again for Mike Gibbs with whom he appeared on Tanglewood 63 (1971).

“Mike Gibbs was very open to listening to all types of music. I remember going over to his house with armfuls of Motown records which he loved. The only surprising thing was that he seemed unfamiliar with a lot of it. Musicians like Gibbs seemed to be just starting to be aware of a whole world of music outside jazz. I was happy to inject my rock style into the mix. I was fashionable for about five minutes!”

Spedding left Nucleus after their second album We’ll Talk About it Later. His musical proclivities became incompatible with those of Carr, whose motives he had also begun to question. “I was the only guy in Nucleus, I believe, who was from the rock world. Not many rock guitarists in 1969/70 could fit in easily with musicians coming from jazz.” Spedding was by this time seeking a simpler, more direct form of music-making far removed from the restrictive attitudes he encountered with the likes of Nucleus.

He did one more turn as a jobbing jazzer for his old comrade, saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith, with whom he had played in the Battered Ornaments and who was now working on his own long-overdue solo album A Story Ended (1972) for Bronze. Heckstall-Smith had roped in several of his Colosseum bandmates including Jon Hiseman, Dave Greenslade and Chris Farlowe to help out, with Pete Brown supplying lyrics.

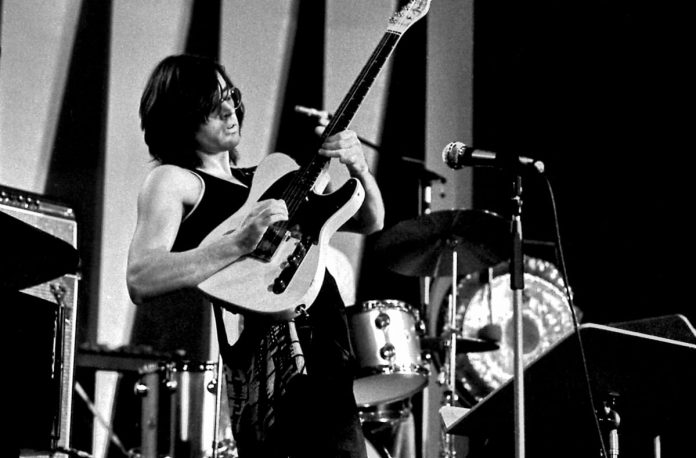

“I do remember working on a track from the album called The Pirate’s Dream”, recalls Spedding. “Dick had written it as a guitar and sax duet with Clem Clemson but Clem wasn’t around for some reason and I got hired instead. Dick wrote out the whole thing for me to play, mostly in unison with the tenor sax. A very challenging bit of sight-reading! I remember there’s a funny photo of me on the back of the album cover biting my nails as I stress out over the demands of the chart!”

Looking for a break from the session circuit, Spedding accepted an invitation to join former Free bassist, Andy Fraser who was putting together a rock band called band Sharks with Steve “Snips” Parsons as lead vocalist. “Andy Fraser was a wonderful bass player, writer and musician. After Jack, I can say I’ve been very lucky with my bass players. Two of the finest bassists to come out of rock music.”

When, for personal reasons, Fraser left soon after the release of their favourably received debut album, First Water (1973), Spedding and Parsons persevered bringing in Memphis bass player “Busta Cherry” Jones as Fraser’s replacement (following a recommendation from Mick Jagger) for their second album, Jab It In Your Eye (1974). The unwarranted commercial failure of the second album saw Island Records ill-disposed to sanction a third, and the band split up before the year was out.

Resorting to session work and life as a journeyman musician, Spedding has kept himself gainfully employed for the past 50 years, and in-between times has released his own unrestrained if often under-appreciated solo albums. In 2015 he released Joyland for Cleopatra Records with an impressive line-up featuring Ian McShane, Bryan Ferry, Robert Gordon and Johnny Marr among others. “It was Cleopatra’s idea to have guest stars. My writing partner Steve Parsons helped me produce it and contributed quite a lot to it. I was happy to go along with everything and I very much like the end result.”

If only Hendrix could see him now.