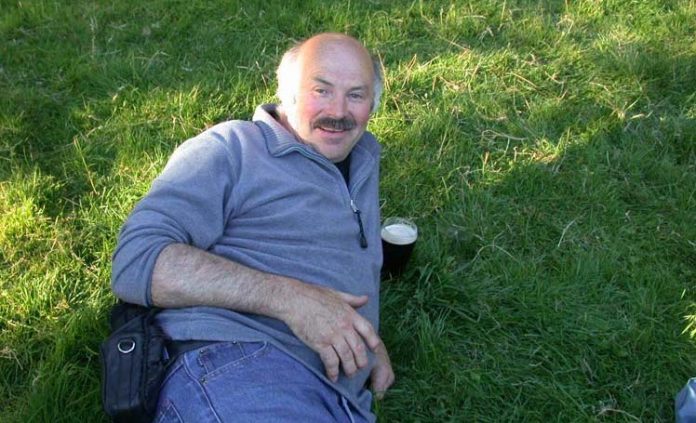

Mention last time of my jazz-book discovery in Appleby (The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, by Cook & Morton, awaiting liberation from The Hub for £1) made me realise I was not 200 yards from the entrance to Appleby Castle, site of the now much-missed Appleby Jazz Festival. The person missing it most is Neil Ferber, who started it all in 1989 with a speculative appearance at his home in Bongate by the Stan Tracey Quartet. Expecting a few besotted aficionados to turn up, he had to find room for an audience of 200. That’s jazz for you, and the rest became an 18-year-old history.

Neil had come across Stan and others at the Bull’s Head, Barnes, when he was living and working in London. The festival soon decamped to a marquee erected in the grounds of the nearby castle and became an annual and burgeoning convocation of Traceyites. Many who were associated with Stan – which was most of the important London crowd at the time – made the journey to Cumbria and loved the event as much as the punters. It was only when the 2007 festival was almost rained off, decimating attendance figures, that Neil, bedevilled by other considerations as well, decided it was time to pull up the tent pegs.

‘Like many other recurring jazz promotions that from the outside appear to be run by a team of at least 20 full-time professionals, Appleby centred largely on one multi-tasking go-getter and his volunteers’

Like many other recurring jazz promotions that from the outside appear to be run by a team of at least 20 full-time professionals, Appleby centred largely on one multi-tasking go-getter (Neil) and his volunteers. Funding, as everywhere else, was a continuing energy drain. Subvention from Northern Rock, the demutualised building society based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, ended with the firm’s spectacular collapse before nationalisation in 2008. A three-year guarantee of financial support from the quango Cumbria Vision had also finished. The Arts Council of England had never granted the festival core funding – money from that source was always “a lottery”. But funding for the previous three years had enabled the festival to employ more help, pay musicians better (including bringing some across from the Continent), and commission music.

If not strictly exponential, the growth and consolidation of the festival had meant more work for virtually the same number of helpers. Writing at Christmas 2007 and in reflective, nay decisive, mood, he told supporters that there’d be no festival in 2008: “In the beginning it was easy for volunteers to put in their time for free”, he said, “but the sheer amount of of work involved just in the physical setting up of a festival with the size it has become is more than one can ask of volunteers, and it has to be paid for.

“I have done this sort of funding application work for 18 years and have always seen it as a necessary evil. Since this year’s festival, I’ve had neither the energy nor the motivation to start another round of searching for funds”.

And that was that. No-one blamed him. Quite the opposite. “Most successful jazz festivals are run largely by volunteers”, he told me. “That’s just the way it is”.

The Tracey quartet at that first gig was the one that had come together 10 years before – Stan, his drummer son Clark, bassist Roy Babbington and saxophonist Art Themen. Their stop at a riverside mill house in old Westmorland must have been a familiarly bizarre aspect of the jazz life: they’d just completed a week at Scott’s and were on their way to Chicago via the Edinburgh Festival. Still, 200 in the audience for a then ad-hoc event must have gratified them.

By 1992, the line-up at Appleby included Bryan Spring, Evan Parker, Stan’s quartet again, Tina May, Don Weller and Alan Skidmore, in various permutations and/or bands. Parker’s presence might have surprised, but he went down a treat once Neil had said he (Parker) could play three-parts at once on a solo instrument. Stan’s wonderful octet made an early appearance, then boasting the recent arrival of trumpeter Guy Barker. Other additions to the festival roster over the years were the Peter King Quintet, the Iain Dixon Quartet, Nigel Hitchcock (in a duo with Stan at the 1993 show and elsewhere), and pianists Steve Melling and Dave Newton, alongside many more.

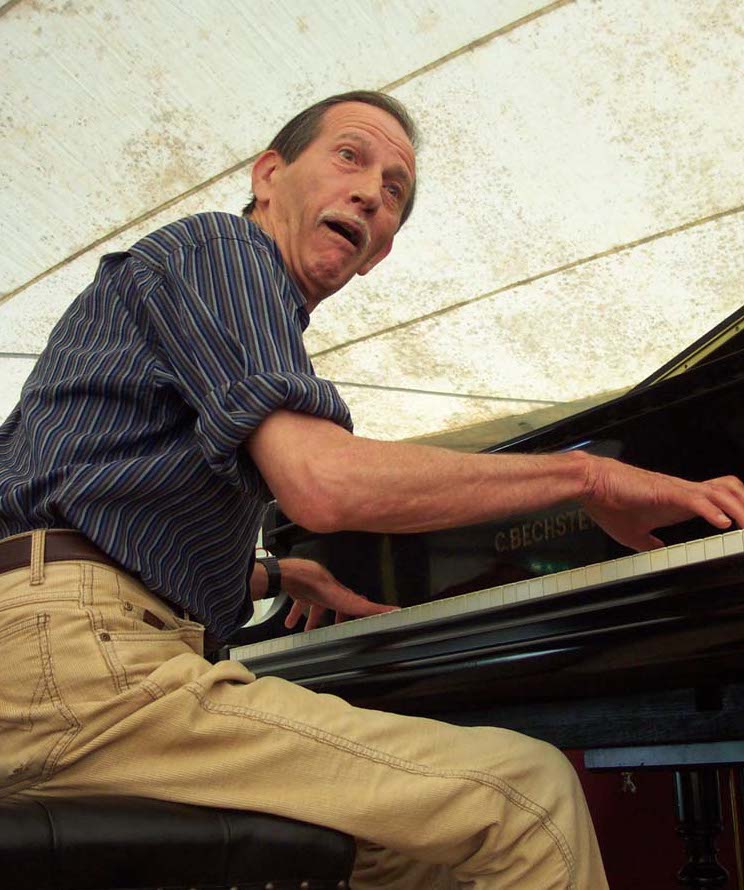

Appleby regulars continued to appear as well as those beginning to form the nexus of a new generation of UK jazz musicians, including saxophonists Tim Whitehead and Dave O’Higgins, trumpeter Gerard Presencer and singer Stacey Kent. Variety bloomed as well. In 1996, King performed not only with his own quartet but also with the Lyric Quartet, a classical string foursome for which he’d written two commissioned works for quartet and alto, based on his love of Bartok’s music. Gordon Beck (pictured left in 2003 making another remarkable discovery) performed a new suite based on train journeys, appropriate in Appleby as a stop on the Settle-Carlisle run.

Solo gigs and duos were frequent. As well as Parker, soloists included guitarists Gary Potter and Martin Taylor, and pianists Beck and Newton; among many duos were Pia di Vita & Huw Warren, Stan Tracey & Presencer, Chris Biscoe & Ben Davis, and King & Beck. Expansion on stage mirrored the festival’s growth. As well as Tracey’s octet, Alan Barnes appeared with a nonet, saxophonist John Surman with a brass project and Don Weller with a big band. Most became regulars, buoyed by Cumbrian fresh air. There were other hefty presentations as the millennium turned. They culminated in the Appleby Festival Big Band in 2001, a long-cherished Ferber project made possible by the Friends of Appleby.

Neil describes the festival as “a coming together” of appreciative musicians and fans and speaks highly of the great British players of Stan Tracey’s generation, who are gradually being lost to us. Appleby festival stories abound: “I had a piano tuner who drove all the way back to his home in Nottingham to make a new bass string to replace a dud one on one of the festival instruments and then drove all the way back to replace it”.

Critics who visited Appleby and wrote up the festival realised it was one of the few places in Britain where all the country’s celebrated jazz musicians – meaning those who met their American counterparts on equal terms – could be heard in one place.

Still, there are six “live at Appleby” records in the catalogue: Three Tenors, featuring the saxes of Mornington Lockett, Art Themen and Don Weller (Trio Records); The Stan Tracey Orchestra (Resteamed Records); pianists Mark Edwards and John Donaldson (Trio Records); Appleby Blues, by the Gordon Beck Trio (Art of Life); Live In Appleby: The Lydian Sound Orchestra (Almar); and The Last Time I Saw You, by the Stan Tracey Trio with Peter King – the title track was recorded at the festival (Trio Records). Neil himself has set up a festival website, with more information pending, to record the history of the event.

Postscript: YouTube is a fountain of jazz clips. Here’s one of Peter King playing Charlie Parker’s alto sax at a Christie’s auction in 2001. You have to be some kind of musician to do that and the wonderfully sharp-suited King is unfazed. Sure enough, he and his quintet – Steve Melling, Gerard Presencer, bassist Jeremy Brown and drummer Stephen Keogh were at Appleby that year, when King and Melling also appeared in the Appleby Festival Big Band.