Jen Wilson is capable of writing a gender-neutral book on jazz in Wales of which the gender-specific one she’s written here could have been a sequel. Even Welsh jazz fans might suspect that the former would be uneven in sweep and thin on detail during a hundred-year survey. It did exist, at least after jazz had emerged from its late 19th-century beginnings. But would there have been a 320-page book in it? If so, wouldn’t her feminist angle have been an albeit worthy and necessary follow-up? Moot points.

Maybe in terms of knowledge we are all behind the times. Wilson, a jazz pianist, founded the Jazz Heritage Wales archive. Jazz followers beyond Wales who associate the country only with post-1950 personalities and events, such as pianist Dill Jones and the much-missed Brecon Jazz festival, may find Wilson’s approach illuminating – historical re-evaluation is often about adjusting and redressing imbalances as well as delving deep and painting a wider picture. But striving to accomplish the last can confuse a deliberately neglected female role with one as equally forgotten as its male equivalent.

The focus of the book is inevitably on the populous and industrial south. Among the musical venues mentioned, the north features once (Payne’s Café, Llandudno, haunt of the clarinettist Harry Parry). Also unavoidable is the difficulty of sifting the genuine article of jazz from its adulterated manifestations; it’s had a pretty consistent and related evolution separate from its influence, but Wilson takes in everything from visits by the Fisk Jubilee Singers to the Confetti Battle and Dance “with full orchestra” at the Mumbles Pier Pavilion in Swansea. A 1919 “Buy a Jazz Band” advert for peace celebrations in a Swansea music shop included Scottish bagpipes, English kazoos, French whistles and a pair of “Nigger Clappers”. (Wilson makes the necessary disclaimers for terms no longer acceptable). There was much blacking-up: Harry Collins’s Minstrels, in a picture from the Cynon Valley Museum, might be coalminers who’d bypassed the pithead baths on their way to the theatre from a colliery shift.

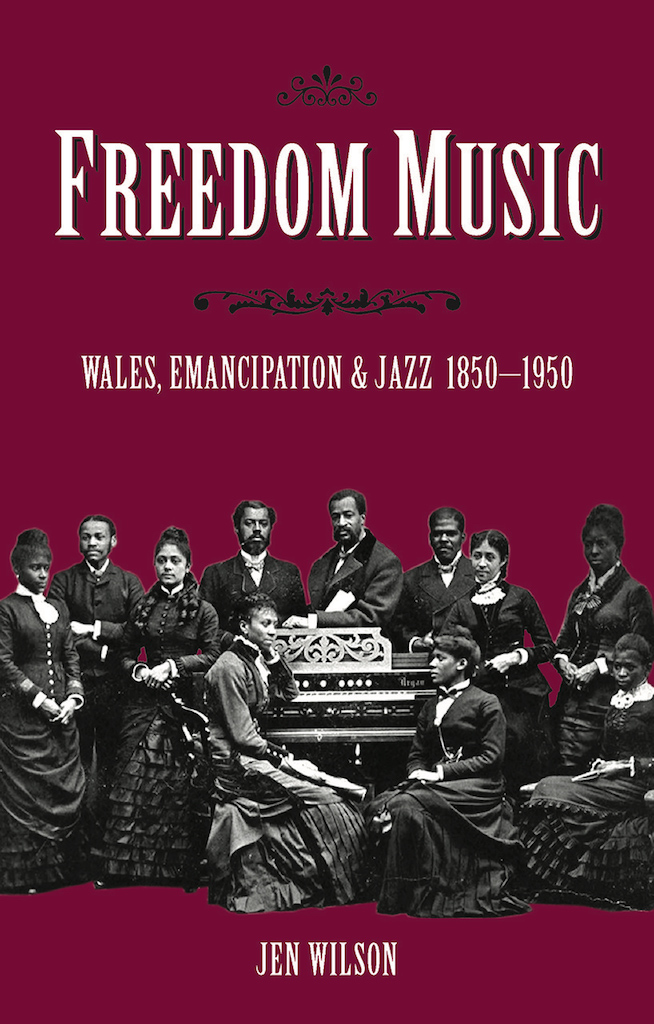

From the female angle, Wilson’s book offers further evidence of a universal but hitherto hazy truth about women’s roles. In general terms its enthusiasm and scholarship cast light on many aspects of the country often ignored if known at all, such as the role of its manufacturers and shipping magnates in the slave trade (the Fisk Jubilee Singers included in its ranks former slaves or the progeny of enslaved parents).

If her concentration on the distaff side needs justification it’s found on page 233, where the critic Spike Hughes, quoted in his 1951 autobiography, opines that the presence of a woman in the company of male musicians is “embarrassing and unnatural”. As Wilson writes, “If women did, in fact, display an intellectual understanding of the music and conveyed it through a high level of performance, they were regarded as having masculine characteristics or portraying deviancy”. She believes this is no longer the case, although old preconceived notions “can occasionally be sniffed, wafting on hot air”. The vestiges of such hot air waft through Welsh hills and vales no less and no more than anywhere else in the jazz world.

Freedom Music: Wales, Emancipation & Jazz 1850-1950, by Jen Wilson. University of Wales Press, paperback £24.99; 322pp