You know that thing when your desk gets so cluttered that if you slide something more onto the front something falls off the back with a clunk. I sometimes sense that reputations are like that. Some hot new exponent comes on the scene and doink a previously admired artist slips out of view. So torrential is the flow of new material in jazz that it’s very hard, unless you are one of those “fans” who draws a chronological line in the sand, to maintain a relationship with older and or long-established careers. The kind of listener who says “I don’t play anything recorded after 1955” always makes me think of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, who sits in her yellowing wedding dress and beside her mouse-eaten bridal cake, eternally stuck in the day decades before when she was jilted by Mr Notquiteright, or as I sometimes think of him, Mr Sensible.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this recently and specifically about a late night telephone conversation I had with the late Richard Cook. We were both on a second or possibly third malt and musing fretfully on our self-imposed role as two little Dutch boys with our fingers in the dyke of a large book that was trying to control the flow of what was then considered the “CD revolution”. Every mail brought the slap of a padded envelope or three on the mat. Every slap was an hour that would have to be devoted to the Next Big Thing, or a “fresh face on the scene”, or a “stirring new voice”, and we devotedly unpeeled sealing strips, ripped off cellophane and loaded the tray.

“When did you last sit down and listen to a Charlie Parker record?” Richard asked, sighingly. I couldn’t remember. Or some Lester Young? Or Jay McShann? It’s an easy regret to redress. You simply go to the shelf, take down a disc, put it on and wallow. Meanwhile the mat piles up the way milk bottles used to accumulate on the step when some lonely old-timer down the street had coughed his last.

I was thinking about this last night and thinking “Yes, it’s easy to put right; you just need to make the time and the commitment”. There is, though, a more insidious form of neglect and regret. Not all our heroes die at 35 or 29. Some of them have the nerve to live on for decades, working quietly, producing wonderful creative work, probably giving delight to thousands, and maybe winning new fans with every passing year. But those of us “in the business” are prone to think “Ah, another record by X; we know pretty much what this is going to sound like; he’s still playing tenor saxophone; we know the rhythm section guys; he hasn’t surrounded himself with DJs, theremins, Tuvan throat singers or field recordings of creaking gates”. And the temptation is to file that record quietly alongside the decades-long discography, unheard but tacitly prejudged.

I confess to doing this all the time. One of the joys of reviewing is that it makes me listen to things that might otherwise share that unforgivable fate. If our music is a long game, and Richard was very much a five-day Test man when it came to both jazz and clicky ba’, then it’s reasonable to hope that “late” work might have acquired a patina of experience, technical confidence, philosophical depth and all the other characteristics to look for in “heritage” culture.

Needless to say, some artists do their creative work when young – like mathematicians – and then spend the rest of their lives either retreading it, or teaching youngsters how to do it, but making a respectable living, which we shouldn’t grudge. Some artists were in their pomp at 25, passed on at 26, and may well be lucky to have done so. Decline is never much fun to watch, and temporising is a faintly tawdry business.

My mother (who is in her 90s and seemingly indestructible, despite various recent crises) decided who and what I was at about age 16 and has ever since based her impressions of me on that early and now outdated template. Families are like this. We lose the ability to surprise each other, as friends can do. There is nothing more delightful than to encounter a name afresh and to realise that one’s neatly pigeonholed summation of him or her was wide of the mark by several metres and probably 30 years.

All of which is a hell of a long way round to say that I have been listening to Benny Golson, with a smile, a faint blush and at times the first prickle of a tear of joy. If you had asked me six months ago for a view on Golson, I would have reeled off a few pretty obvious points. I’ve long considered “Whisper Not” and “I Remember Clifford” to be among the very greatest of all jazz compositions, with “Stablemates”, “Blues March”, “Killer Joe” and “Along Came Betty” high in the tables. I would point to his work with the Messengers and the Jazztet, to early albums such as The Modern Touch, or Gone With Golson, which came out 60 years ago.

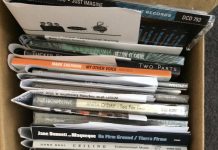

Mr Golson turned 90 on January 25 [and will be man of the moment at this year’s Ystad jazz festival]. He’s still with us, but my impression of him was forged so long ago it’s turned to stone. I went to the shelves and, shamingly, there are things there by Benny that have sat unopened since the day they arrived in the mail. And yet, any one of them might change my sense of who he is and what his art is by anything up to one-eighty degrees. That would be shaming. I haven’t listened to them yet. They are sitting on my desk, by way of reproach. I’m compiling a mental list of that hard-to-define cohort of jazz artists whose standing, in my eyes at least, hasn’t been given a chance to change or evolve or overturn.

I’ve had my own Havisham moment. Just for the moment, I’m not going to listen to anything that was released after 31 January 2018. Not until I’ve listened to Benny’s later wisdom. Or not unless you ask me to review something!