There was a question on one of the brainier TV quiz shows recently – QI or some such – that posed a kind of odd-man-out scenario. There were four portraits of the 20th century’s favourite boo-boys: Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Franco. All four were supposed to dislike something, but one of them was actually rather partial.

The answer, somewhat predictably, was jazz and the arguable exception Mussolini. Needless to say any enjoyment he might have taken from syncopated music and swing was strictly unofficial and counter to fascism’s racial exclusivism. His son Romano (born 1927, so exculpated from wartime guilt) became a distinguished jazz pianist.

It’s known that Italy was an early adopter of African-American styles, hence the surprisingly early terminus a quo of David Chapman’s fine and learned account. Milan audiences at the Teatro Eden took to creole music as early as 1904, long before American military bands and their records started crossing the Atlantic.

We’re used to the idea that Ernest Ansermet was one of the first serious proponents of jazz music – his comments about Sidney Bechet are regularly anthologised – but Alfredo Casella, who in the late 20s conducted the Boston Pops, was also an early and serious admirer whose belief that jazz represented an irruption of Dionysian energy coincided precisely with the identical suspicion of opponents like Anton Giulio Bragaglia.

When it comes to actual exponents, Chapman gives proper place to Pippo Barzizza and his immensely popular Blue Star Orchestra, which adopted a version of the Paul Whiteman style and naturalised it for Italian audiences. The first bona fide Italian jazz star was certainly accordionist and bandleader Gorni Kramer (he was actually Francesco Kramer Gorni), who survived the wartime jazz underground and suppression by the national broadcaster and who was still something of a star when I first visited Italy in the 1960s.

‘I wonder if he’s preparing a second volume or whether his own tastes sit better with the earlier years and without having to deal with the barbaric, free-jazz yawp of later visitors like Gato Barbieri’

Anyone who has seen The Talented Mr Ripley will remember Jude Law (shortly to be replaced in life by Matt Damon’s Tom Ripley) belting out “Tu vuò’ fà l’americano”, originally popularised in 1956 by Renato Carosone. The transatlantic theme of Patricia Highsmith’s original novel is relevant to Chapman’s story of Italian jazz, with the obvious connections and tensions between European culture and mores and the internationalising aspects of American culture, which was often dominated by Italian-American and Jewish musicians.

It makes for a fascinating story that emerges more often between the lines of Chapman’s book than as a consistently argued thesis, leaving the book all the more readable as a result. I’m guessing that names like Giuseppe Creatore and Carlos Benzi aren’t much known outside Italy now and that most modern music students cut into the Italian story with futurismo and the briefly exciting promise of its intonarumori or noise-making instruments. Chapman gives this episode exactly as long as it deserves, treating its internal contradictions with gentle tolerance.

He is, throughout, a sympathetic and obviously committed guide, with an attractively open-minded acceptance of what is (now very respectably) known as “queer aesthetics”. Previous books include Universal Hunks, which is art-historical rather than niche-gay and Sandow The Magnificent, a strangely moving account of bodybuilder Eugen Sandow, who can be fragmentarily viewed in full ripple on YouTube.

Chapman cuts off his tale too early to take account of figures like Giorgio Gaslini or Enrico Pieranunzi, which is a shame but perfectly in keeping with his chosen post-war terminus ad quem. I wonder if he’s preparing a second volume or whether his own tastes sit better with the earlier years and without having to deal with the barbaric, free-jazz yawp of later visitors like Gato Barbieri, or the sub-Ripley antics of Chet Baker and his contessas. For the moment, though, va bene.

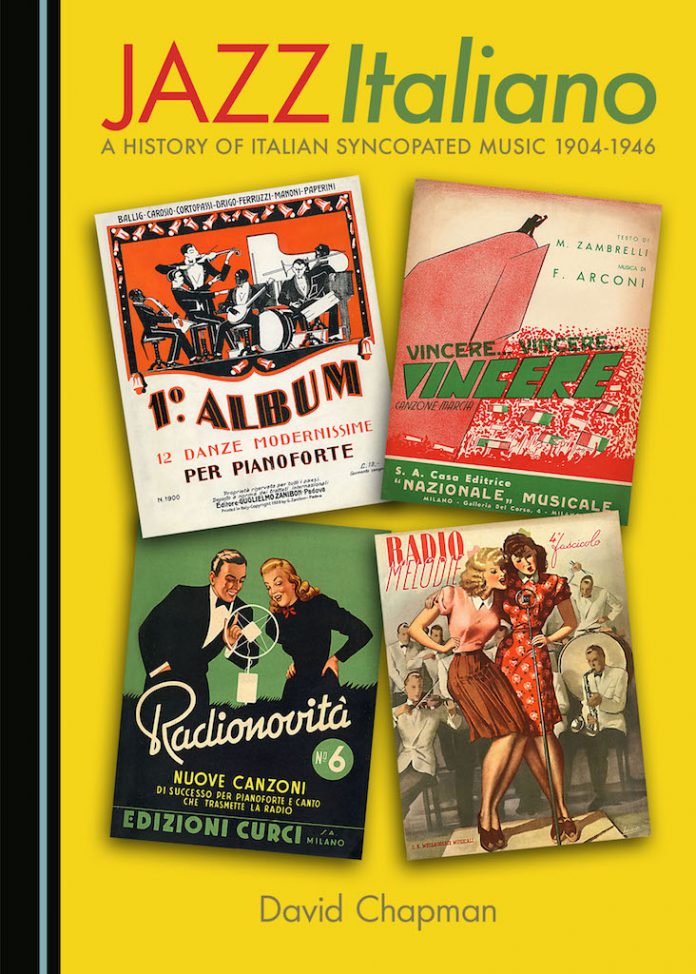

Jazz Italiano: A History Of Italian Syncopated Music, 1904-1946 by David Chapman. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ill. b&w, 244pp. ISBN (10) 1-5275-2019-6 // (13) 978-1-5275-2019-6