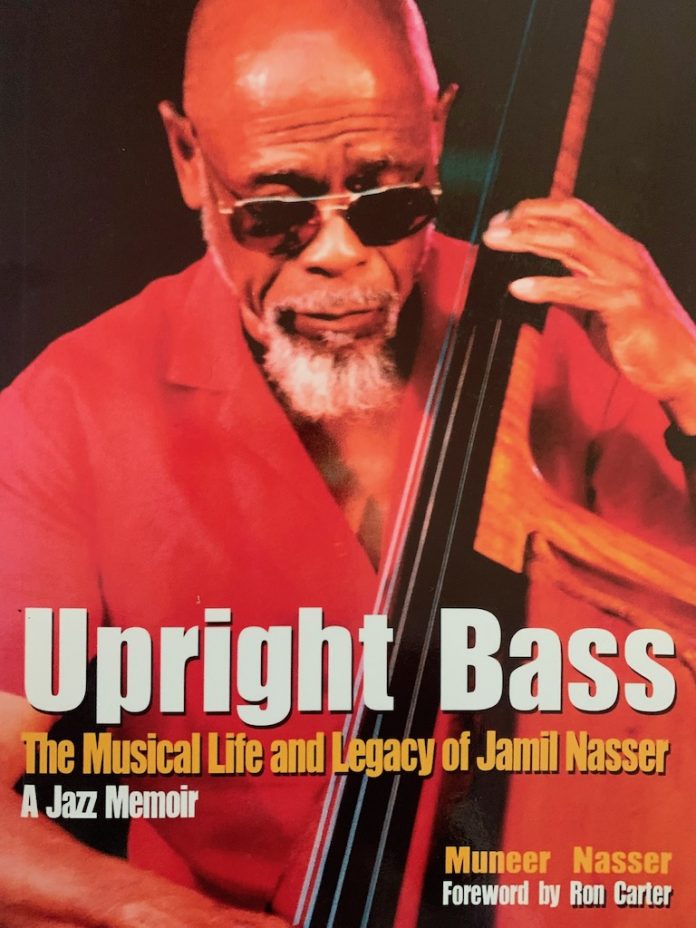

You may know him as George Joyner, Jamil Sulieman or Jamil Nasser but the last name is probably best known and the one he used for most of his last years. The book was written by his son Muneer Nasser, himself a trumpeter player, composer and jazz historian. The story was told by Jamil to his son Muneer in a series of interviews towards the end of his life when he was in his 70s but before the onset of Alzheimer’s disease which eventually restricted his ability to communicate.

Muneer’s narrative chronicles the life and work of his father in great detail, covering the years from Jamil’s arrival in NYC in 1956 until his death in 2010 aged 77. During a busy life as a musician he played bass with many important musicians including Donald Byrd, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Red Garland, Phineas Newborn, Ahmad Jamal and Lester Young. He covers his experiences with these people and many more. He was also vice president of the Jazz Foundation of America and he supported US Congressman John Conyers’ Resolution HR-57 designating jazz as a national treasure. A foreword was written by Ron Carter who claims Nasser was his friend.

Jamil Nasser spent most of his life as a working bass player and fighting hard to improve the conditions of fellow musicians and himself in the face of union restrictions against jazz players and what he felt was an establishment that made working conditions difficult unless you followed their rules and methods of operation. It was hard work but according to this narrative he was mostly successful although he claims to have suffered periods when he was blacklisted and unable to work.

Nasser tells of finding it nearly impossible to record for Prestige because he was not a junkie. He put on shades and started talking like them but they soon caught him out

His early experience was playing in NYC as George Joyner, the name he received at birth and avoiding the heavy jazz culture that operated at the time. Nasser tells of finding it nearly impossible to record for Prestige because he was not a junkie. He put on shades and started talking like them but they soon caught him out, he says. “Clean musicians were ostracised because we didn’t need to see the man before the session or after it ended”. He did record on The Big Sound with Gene Ammons but claims that Jug sold his plane ticket in California to buy junk and eventually arrived in NYC by bus, without his tenor. Coltrane loaned him his which is why Trane played alto on that recording, a rarity for him. And a puzzle to enthusiasts over the years!

Nasser tells of Red Garland asking him “not to knock junk” without trying it. So he did, just once. He could hardly make the gig, had to hold on to the piano to play and was violently sick all night. He never touched it again. Other anecdotes include having to reluctantly refuse to let Paul Chambers sleep on his sofa when he was strung out because he had pus-filled sores all over his arm and “my kids use that sofa”. Chambers said he understood and left.

A gig at the Village Vanguard with Sonny Rollins, Donald Byrd, Gil Coggins, Joyner and Roy Haynes ended abruptly when Rollins kept the band waiting for 50 minutes before arriving, playing solo tenor for 10 minutes at the entrance and then moving to the bandstand to play more solo. The musicians tired of standing by their instruments and launched into a blues. Rollins fired them all for not respecting him and hired Elvin Jones and Wilbur Ware to make it a trio gig and, as it turned out, jazz history.

Nasser went on to play many dates, record sessions, a tour of Africa with Idrees Sulieman and long standing engagements with pianists Oscar Dennard, Phineas Newborn, Red Garland and Al Haig. He played on a Blue Note date with Hank Mobley called Curtain Call and was busy most of the time even though many people tried to blacklist him for his strong views. He was quite scathing about the state of jazz in the 1980s claiming that it was all technical training in the schools and colleges and no soul. He claimed that bebop was the true music and not funk, fusion, rap or any derivatives and straightahead jazz was the real thing. He said that in the 1950s you could tell a musician as soon as he played three notes but today (the 80s) they all sounded exactly the same. He was equally dismissive about free jazz. I dread to think what he would have made of the 2019 scene.

The book is enlightening about the jazz scene from 1956 to 2000 and a fascinating portrait of a straightahead bass player who, perhaps for many reasons, was not as well known as he should have been. He was an honest, skilled bass man who always told it exactly as he saw it but didn’t, maybe, make too many friends in the jazz world.

Published by Muneer Nasser, Vertical Visions Press. Pb, pp 254. ISBN 9780692895986