Leon Morris reports

The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, now in its 52nd year, treats jazz more as an idea, or perhaps a launching pad, than a musical genre.

Originally conceived by George Wein as a celebration of the rich musical and cultural traditions of New Orleans and the Louisiana area, Jazz Fest, as it is now popularly known, has grown over the years to embrace rock and pop.

While this can be explained as a nod to the profound influence of New Orleans traditions on the development of popular music, it is has also become a commercial imperative. Jazz Fest adds around $400 million to the local economy and the festival foundation distributes annual profits to a wide range of musical and cultural initiatives.

Jazz Fest manages to strike a workable balance between headline acts like this year’s Lizzo, Ed Sheeran and Dead & Company (a Grateful Dead offshoot) and specialist stages catering for regional and niche genres including modern and trad jazz, blues, gospel, Cajun and zydeco.

The huge scale of the event helps: 580 separate music acts, around 2,500 individual musicians, perform on 12 separate stages, for seven days, over two weekends. Around 450,000 people attend, with some days attracting over 100,000, subject to the popularity of the headline acts and the wildly fluctuating tropical weather.

The converted racecourse track includes curated exhibits, craft stalls and restaurant quality food. For some devotees, Jazz Fest is a Louisianan foodie-fest with music on the side: think jambalaya, gumbo, beignets, boudin, crawfish étouffée, and po boys (French-style bread rolls with catfish, fried oyster or soft-shell crab).

Of the 580 acts, around 500 are locals, testament to the extraordinary depth and quality of musical talent that is the hallmark of this city’s impact: birth-place of jazz, New Orleans funk and bounce (intense dance sound that made “twerking” mainstream). And it was in a New Orleans studio that drummer Earl Palmer first recorded the back-beat behind Little Richard. The back-beat, as Wynton Marsalis has explained, has gone on to become the dominant rhythm of 20th and 21st century.

This musical pedigree dates back to the slave era, when French colonists, unlike their British counterparts, allowed African slaves to gather on Sundays in what became known as Congo Square (now Louis Armstrong Park). The music that evolved permeates the city. As local poet Lee Grue once told me, “Music bubbles up from the ground.”

It is this history, combined with a level of musicianship honed over lifetimes of performing on stage and in street parades, that makes traditional marching bands so infectiously danceable. After all, one of their main roles is the second line celebration to send off departed friends, family and fellow musicians.

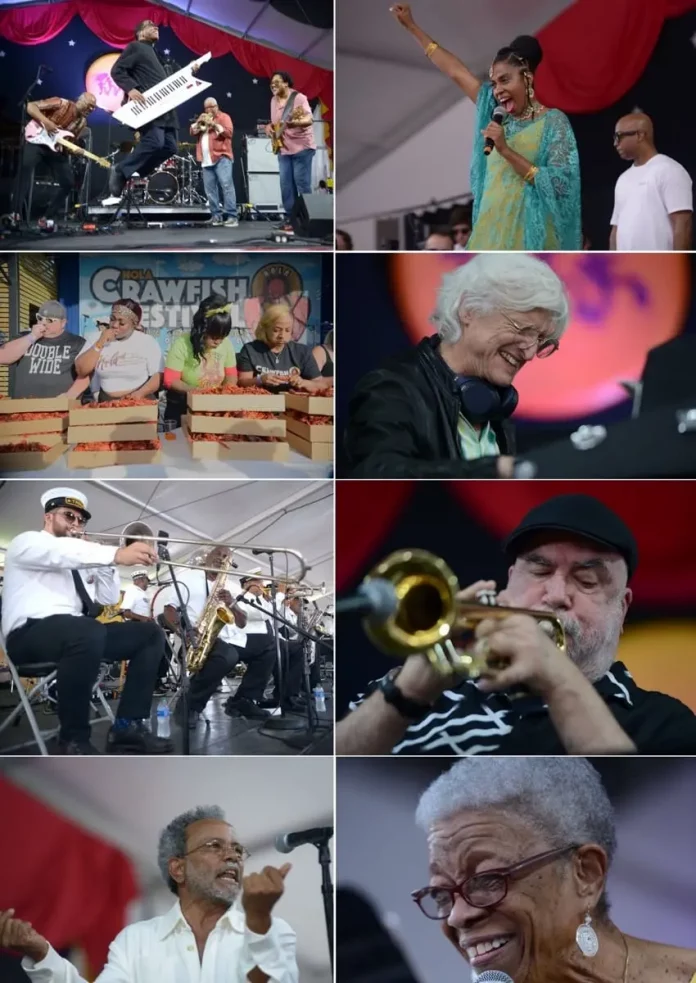

This richness of musical history makes the Economy Hall, Jazz Fest’s traditional tent, perennially popular. My highlight was the Tremé Brass Band, with a rousing set of jazz and New Orleans standards. A long list of illustrious local musicians, including trumpeters and band-leaders Greg Stafford and Leroy Jones, demonstrated extraordinary depth of knowledge and technical skill, while the Dixieland traditions of Doc Paulin continued through the next generations of the Paulin Brothers Band.

Family dynasties were ubiquitous. The Marsalis family was represented by drummer Jason and trombonist, Delfeayo, both acknowledging the passing of their father and family patriarch, Ellis Marsalis Jr., who died from Covid-19 complications in April 2021.

The Nevilles were represented by Charles, the last performing brother, with sister Charmaine and Aaron’s son, Ivan, now mentoring the next generations of Nevilles in the New Orleans funk, blues and reggae traditions.

Troy “Trombone Shorty’ Andrews has become a powerhouse performer, and was honoured with closing the main stage on the final Sunday. Cousins James and Glen David were exceptional but unpredictable talents. Glen David, on song, is arguably the most exhilarating live performer in the city – Satchmo on steroids.

Jon Batiste, winner of five Grammy awards last year, including Best Album, has become the popular face of New Orleans music. He led his own band and guested on sets with Trombone Shorty, Soul Rebels and Mumford & Sons.

The Jordan family paid homage to the recent loss of their father, the educator and avant-garde improviser, Kidd Jordan. Stephanie’s rendition of Eden Ahbez’s Nature Boy was especially poignant, with that moving line “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return.”

Three extraordinary vocal performances stood out in the jazz-tent programme. John Boutté was a warm and generous performer, his mellifluous voice having a gravelly, streetwise tinge. His theme song from the HBO Tremé television series was a crowd favourite. It’s probably only his reluctance to leave home that prevents him from being a household name.

Dee Dee Bridgewater paid tribute to Betty Carter, Louis Armstrong and Chick Corea, demonstrating why she is so well respected as an elder and mentor. Her vocals and performance were assured and accurate. She can be both subtle and sassy. In her own words, “You don’t have to be cold just because you’re old” – something that could also be said about perennial local favourite, Germaine Bazzle, still performing at 91.

Jazzmeia Horn was my find of the festival. She is a prodigious new talent – the best new female vocalist I have heard since Cassandra Wilson. Winner of the Thelonious Monk Institute International Jazz Competition in 2015, she has now formed her own label to pursue big-band composing, arrangements and recording. In concert, she was captivating.

Elsewhere in the jazz tent, some old favourites excelled. Vincent Herring’s Something Else was an assembly of all-stars living up to its name. Randy Brecker and James Carter traded licks on trumpet and sax with astonishing virtuosity.

Nicholas Payton continues his sophisticated, considered and hypnotically innovative artistry. While he now mostly plays keyboards, his tone on the trumpet remains exceptional – Doc Cheatham once compared him to King Oliver.

Trumpets ruled the stage with the Trumpet Mafia – a joyous gathering of mass trumpets and brass from the best young exponents in the city. Christian McBride demonstrated why he is so highly regarded on bass and Artemis reclaimed the jazz stage for female instrumentalists.

Terence Blanchard was probably the pick of the local artists – his compositions clearly showed the benefits of working in film and opera, and he played with a deft, but powerful style that was at times breathtaking.

Blanchard joined Herbie Hancock to close the jazz stage on the final day. The jazz stage, in the city that gave birth to jazz, has been home to extraordinary moments as jazz greats such as Sonny Rollins and Pharoah Sanders have risen to the occasion. There was a palpable sense of excitement as Herbie took the stage – he is revered as perhaps the last giant of his generation still performing. The playing was sublime, the use of electronics to modify vocals and guitar was layered and nuanced, never flashy. Everything was just so. Until Herbie dances across the stage, keyboard across his shoulder, and then leaps in the air – at the age of 83. A fitting end to a memorable concert and festival.

The party, however, doesn’t stop when the festival closes each day at 7pm. It shifts to hundreds of gigs in clubs and music halls throughout the city. Preservation Hall and the Palm Court Jazz Café are the go-to venues for trad fans; Snug Harbour is probably the premium venue for modern jazz. Herlin Riley on drums and Donald Harrison on saxophone led intimate sets. Paying homage to heartfelt recent losses of Wayne Shorter, Ahmad Jamal, McCoy Tyner and Ellis Marsalis, Herlin took the club on a rhythmic journey, while Big Chief Donald Harrison demonstrated the evolution of jazz, including his role in nouveau swing, smooth jazz and Mardi Gras Indian street music.

In what has become known as the “daze in between”, the three-day break between the two weekends of festival programming, one-off events and smaller festivals spring up to meet the seemingly insatiable appetite of locals and visitors. For the last seven years a Crawfish Festival has billed itself as “Music Crawfish Beer”, showcasing local musicians and all-star bands, with an annual crawfish-eating competition. This year’s winner, the reigning champion, consumed 4.9 lbs of crawfish meat in six minutes.

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, Louisiana, USA, 28 April to 7 May 2023