Charlie Christian, Jack Teagarden, Hot Lips Page, Jimmy Giuffre, Gene Roland, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Herschel Evans, Gene Ramey, Budd Johnson, Sam Price, Harold Land, Eddie Vinson, Leo Wright, Ernie Caceres, Teddy Wilson, Buddy Tate, Eddie Durham, Teddy Buckner, Tyree Glenn, Ornette Coleman, Cedar Walton, Kenny Dorham, Booker Ervin, Arnett Cobb – just a few of the great jazz musicians who came from Texas.

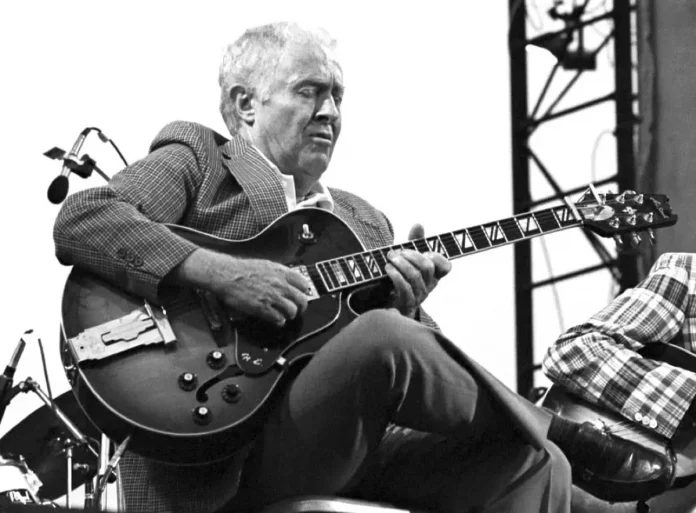

And Herb Ellis, of course, completing a list which shows the Lone Star State as one of the major spawning grounds of jazz talent. Herb was born in McKinney in 1921.

‘I took up the guitar because it was there’, he said. ‘My sister bought me a banjo when I was six. I had a cousin that left a guitar in our old farmhouse – we were out in the country about 40 miles from Dallas – and I became interested in it. I had an older brother who was mechanically inclined and he was interested in it too. There was a competitive thing between us and we both wanted to play it. He tuned it, but I knew he’d tuned it wrong, so I sent for a little book from a mail order catalogue and it taught me to tune the thing properly. After that I taught myself to play it and then taught my brother as well. I never had any tuition at all. I studied music for some years later, but not in relation to the guitar, at North Texas State University. That’s where I met Jimmy Giuffre, Harry Babasin and Gene Roland, and it was with them I made my first contact in jazz. I’m not sure what kind of music I’d played before that – you’ll read some quotes that I played country. Well, that’s all right. Life is one great misquotation. What I actually played were tunes that I heard on the radio, and as far as I was concerned I just played guitar. I didn’t separate the different pieces of music into categories.

‘When you play the guitar you’ve got to be honest. You can’t fake guitar playing. Or you can’t fake it to fool the other guitar players’

‘I really wasn’t jazz orientated at all before college. Our nearest neighbour was maybe half a mile away, so it was a very lonely setting and I never met other musicians, for instance. I was totally dependent on the radio for any influences and the first jazz guitar player I heard on the radio that I was conscious of was George Barnes. That was before I heard Charlie Christian. When I went to college I heard Charlie and that had the most dramatic effect on my music and consequently on my life. At the same time I heard Count Basie with Lester Young and that had a profound effect on me, too. I began listening to Lunceford, Hines and all the name bands. I heard Dizzy at that time – those were his very early days before the bop thing began. Those things formulated my attitude and my likes and dislikes. I’ve remained constant to them. I’m not the sort of player who hears something new and has to go rushing after it. Over the years I’ve known a lot of players like that. Some cat’ll come on the scene with something new and they have to have it as well because they’re terrified of getting left behind. That’s the way to be sure you never have an individual and identifiable style of your own. The guitar, it seems to me, is less prone to that sort of thing because when you play the guitar you’ve got to be honest. You can’t fake guitar playing. Or you can’t fake it to fool the other guitar players. Guitar playing is transparent in that you can tell immediately if a guy has learned his instrument thoroughly. On some of the horns you can perhaps fool people with so-called avant-garde playing, but if you don’t know your chords or progressions on the guitar, it’s going to show up. In this way the strength of character of the leading guitar influences is consistent and it stands out. Someone like Johnny Smith, for instance, who is a totally different player from me, or Tal Farlow, who was probably more responsible for the development from Charlie Christian’s playing than anyone else, or the great players like Jim Hall, Barney Kessel and of course Joe Pass and Kenny Burrell, all have maintained their individual styles and not deviated from them over the years.

‘Like them, in my early days I formulated one road, one way to go in jazz that I liked and could identify with. Once on that road I’ve purposely stayed with it. I may like other avenues in music but they don’t influence me, because I’m a firm believer in sticking with one thing and trying to make it better. These guys you see running scared when some new thing comes along, even if they have a lot of talent and technique, it never means much. It’s never directed at anything with sincerity.

‘The blues element in my playing, which as you say is strong, certainly came from hearing Basie and Lester, but mainly of course from Charlie Christian. He had a very mournful quality to his playing, I thought. He wasn’t known as a blues player like BB King but he had a blues feeling which was very powerful. Where I was reared had something to do with it, too. There was a lot of lonesomeness there. You’d hear freight trains at night, that sort of thing, and although I didn’t realise it at the time, the environment must have influenced my music.

Of Jimmy Giuffre: ‘I feel personally that maybe if he’d stayed on one road he might have had more of an impact than he’s had. That much of a diffused front takes away any definitiveness’

‘You mention the blues trait in Jimmy Giuffre’s music and I know what you mean, but I don’t know if there’s any connection. I suppose there must have been common influences for all of us at North Texas.’ [Interestingly, when Leonard Feather played Kenton’s Reuben’s Blues to Herb in a Blindfold Test, Herb suggested that the soprano sounded like it might have been Giuffre. In fact it was Gene Roland, another Texan. – SV] ‘No matter what kind of music Jimmy’s playing at the moment, and I never know what kind of thing he’s going to be playing from one time to the next, he’s always got the blues thing. He’s never still, and that’s sorta good, but I feel personally that maybe if he’d stayed on one road he might have had more of an impact than he’s had. That much of a diffused front takes away any definitiveness. I love him and I love his music, but for playing I’m more inclined to go with someone like Dizzy or Clark Terry or Milt Jackson. If you walk in to hear Milt Jackson you know what it’s going to be – maybe better than the last time, but you know what you’re going to get. You’re not going to get him playing like somebody else, or another type of music, and that’s very important, I think.

‘But since college, when I roomed with Jimmy, we’ve been close friends. Make no mistake, he’s one hell of a musician. We learned a great deal together and I learned a great deal from him. We listened to records and played together and later on, because of that personal exchange of musical ideas, he wrote an album for me when I was with Norman Granz. Herb Ellis Meets Jimmy Giuffre it was, and it had Bud Shank, Art Pepper, Richie Kamuca and Jimmy on reeds. I had expected him to come up with Four Brothers arrangements but they weren’t. As usual he came up with something else. I like them. At the time I was a little distraught because it put me in a position where I had to read a bit more than I expected.

‘Never liked reading. Hated it! I did it for 17 years in the studio, and was not very good at it, especially at first, but I had to get good enough … I did every thing that I had to do. I never got sent home, so I guess I did it all right.

‘Incidentally I get mixed up. Jimmy and I did an earlier album with Sweets Edison and Oscar and Ray Brown for Norman.

‘Then we did Nothin’ But The Blues for Norman with Roy Eldridge, Stan Getz, Ray Brown and Stan Levey. I’m proud of that one because all the others played so well. I’d like to re-do some of my solos because I think I could have done better with them, but Stanley Getz was at his best on that one and to me Ray Brown is the best bass player there is. No, I’m not being modest. With some albums I do feel I’d like to have jumped my tracks and done some things differently. But a lot of people liked that album. You’ve got to with that quality of players. I was fortunate that I could get them. Stan played beautifully on Tin Roof Blues, but my favourite track and Ray Brown’s too, was Royal Garden. I liked The Midnight Roll that we did for Epic. Roy was on that one too, along with Buddy Tate, Ray Bryant, Jimmy Rowser alternating with Israel Crosby and Frank Assunto. We kept the link with Ray Brown, because that was the first time his tune Gravy Waltz was recorded. He had something of a hit with that.

‘That was right after I had left Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald. I was with Oscar most of the time, six years, and Ella for two years, 1953 until 1959, something like that and this was made right after that.

‘I replaced Barney Kessel with Oscar. Barney had been there a year when he left. As you know we did a host of records, and I had to settle a definitive method for the guitar within the trio right from the start.

‘Some of the best examples were not on the records. We did a lot of so-called “composer” albums, tunes by one composer that we wouldn’t necessarily play out in the clubs or concerts. The best account of that group would be the Stratford album. Have you heard of that? [Under Peterson’s name on Verve import 2304 223. – SV]

Of Oscar Peterson: ‘He ran the whole gamut and it was a good experience. He’s the greatest piano player in the world as far as I’m concerned’

‘The role of the guitar in the trio presented me with the hardest job I’ve had ever. Anybody who would have played that particular role would have found it the same. I had a lot of things to play which Oscar arranged and some of them were with him, playing along with them, but not necessarily unison. Often they’d be harmony parts. Sometimes I’d play contrary parts, sometimes I’d play alone and he’d be playing something different. We had a lot of arrangements and Oscar insisted that you had them all at your finger tips, so it was very, very difficult. Everybody was very impressed with the speed, and thought that was the hardest thing, but actually it wasn’t for me. I got so I could play fast and keep up without trouble. Playing your own solos was the easiest part, that was the ice cream. But playing the backgrounds that Oscar wanted when he was playing – that could be anything from rhythm to comping to bongo effect. He ran the whole gamut and it was a good experience. He’s the greatest piano player in the world as far as I’m concerned. With the arrangement he did most of it – you were free to suggest, but he was so fast at making things up that by the time you’d got a four bar or eight bar section you’d thought of, he’d be already into the next section.

‘I recorded one album round about 1960 after I’d left Oscar and it’s perhaps my favourite album with Oscar as far as my own solo playing is concerned. It’s entitled Hello Herbie and it was on MPS (BMP 20723-4). I flew over to Europe especially to make the album. Bobby Durham was on drums and Sam Jones on bass and Oscar played sensationally.

‘After I left he made the statement that he would never use the guitar integrally in the trio again, which was quite a compliment for me. He meant it out of respect for me, but also that it was so hard and so much rehearsal to get a trio into shape … Now he plays with Joe Pass, sometimes they play together and sometimes they play with bass and drums. But it’s ad lib jamming. They don’t have a lot of hard arrangements to remember.

‘Joe is a brilliant guitarist. I’ve made three albums with him, two for Concord and one for Pablo, and I have nothing but just great things to say about him. I’d hate to choose just one guitarist as my favourite, but he’s certainly one of the all-time greats.

‘Studio work is comparatively easy because you’re home all the time and your hours are regulated, but the work is hard and nerve-wracking. There’s no ifs and ands and no wait a minute. It’s now, and whatever it is you’d better be ready to do it’

‘When I left Oscar I’d been married for a couple of years and we had one child and another one on the way, so I felt a responsibility to my family to quit the road and be home. I stayed at home for almost 17 years, and did studio work, which was a sacrifice because I never liked it. I found it very nervous for me to have to be under the hammer reading. You never knew if it was going to be easy or very hard and it was a painful way to make a living, although I must say I made a very good living at it. I’d got married in 1958 and we moved to Los Angeles then, and stayed home until four or five years ago.

‘In the studios you had to be ready for anything. I was lucky in that in the first week I’d let it be known I was available I began to get lots of work. I played backing rock stars, with big string orchestras, film music, television commercials, all that sort of thing. I put in some years with the television shows, too, like Steve Allen’s and Merv Griffin’s. Before that I did the Danny Kaye and Red Skelton shows amongst others.

‘As far as your life style goes, I suppose the studio work is comparatively easy because you’re home all the time and your hours are regulated, but the work is hard and nerve-wracking. There’s no ifs and ands and no wait a minute. It’s now, and whatever it is you’d better be ready to do it. And you not only have to read it, you have to play it in the style for which it is supposed to be written. Also, live TV is live! It’s hard on the nerves.

‘I’ve been fortunate in that there’s enough demand now for me to be able to concentrate on jazz playing, and I’ve been able to tour Europe, Japan, Australia and so on. I either play alone or sometimes with Barney Kessel and Charlie Byrd, maybe I do eight weeks a year with them and maybe another eight with Barney.

‘I still play a lot at home in LA. But then throughout the time I was in the studios I always kept playing jazz there. I played often with Bill Berry’s LA Band and Juggernaut. I played a lot on Monday nights at Donte’s. Usually I’d have Bill Berry in my group or if he had the group I’d be in it. We’d use Jake Hanna and Ross Tompkins and we had a lot of fun. Bill’s a very good writer. He took the way I played Easter Parade and wrote it up for the big band to feature me and he really captured the feel of the way I played it. He’s a great player, too. I just saw him recently when I took my wife and two daughters to see Sophisticated Ladies. That’s a good show.

‘That show typifies the high calibre of the musicians around LA. Maybe 10 years ago the studio scene in New York got very thin, and it was much more fertile in LA. That’s when many of them came out. I don’t know how the work is for them now, since I’m not involved any more, but I have a feeling it’s not as good as it was.

‘As far as recording is concerned, Concord’s made a big difference for me. Carl Jefferson’s first two albums had me and Joe Pass together and I was on five out of his first six. So far I think I’m on 24 of the Concord issues.

‘Whilst I don’t find much time for personal teaching, I have an interest in the Southwest Guitar Conservatory in San Antonio, Texas. I go there about four times a year for a few days to do some teaching and clinics, so I get to work with young people there.

‘A lot of the kids coming out of the schools are so intent on playing things like the Dorian modes and their scales and things but they don’t play any music. I hope there’s more Emily Remlers coming along to take over from us’

‘Amongst the youngsters there’s a girl called Emily Remler. She came to me about four years ago in New Orleans and said she wanted to take a lesson. I don’t usually work like that and I don’t know why, but this time I agreed. She really didn’t need a lesson – I think she just wanted to play for me. She is a dynamite player. I introduced her to Carl Jefferson and suggested he get her out for a concert, which he did, along with a lot of other guitarists, and now he’s recorded her with Hank Jones, Jake Hanna and Bob Maize (Concord CJ-162). She’s a brilliant guitarist. I think she’ll open up the field for other women and let them know that they can try and emulate her.

‘She’s a good sign for the future of jazz guitar playing. But I think it’s in a pretty good state anyway. Tal Farlow, Kenny Burrell, Jim Hall, Barney, Charlie Byrd, Joe Pass – we’re all enjoying more popularity now than we have in years.

‘A lot of the kids coming out of the schools are so intent on playing things like the Dorian modes and their scales and things and they learn to move all over the guitar but they don’t play any music. They don’t make any swing. I’m afraid they’re going to be very sorry later on. I hope there’s more Emily Remlers coming along to take over from us.’