McCurdy left Rollins to tend to family matters back in Rochester where he stayed away from performing for about a year, working a day job. Then Cannonball Adderley called in 1964. The subsequent 11 years he spent with the Adderley brothers rank as probably the high point of his entire career. As a regular member of the Adderley outfit, Roy was featured on nearly 20 record dates between 1966 and 1975, surely the most with one particular artist. These recordings – some released posthumously – chart the various sounds Cannonball explored in his final decade. They range from the fairly straightahead hard bop and modal vamps of Money In The Pocket (recorded 1966, released later), to the soul jazz and gospel vibe of the Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! phase, and finally, the heavy funk and electronics of his last years.

To dig what Adderley was up to in 1966-67, the recently issued Swingin’ In Seattle is exemplary. In addition to the brothers, the quintet consisted of Joe Zawinul, Victor Gaskin and McCurdy, and an exciting band it was! Cannon’s enthusiasm is infectious, his patented guts and legato approach punctuated by dramatic leaps into the upper register and strangulated shrieks and cries revealing a soul passionately immersed in the music. Zawinul is more ordered on piano, creating a nice contrast to the leader’s outbursts. Brother Nat on cornet is perhaps more conventional than Julian, but he plays very well indeed, a most underrated player.

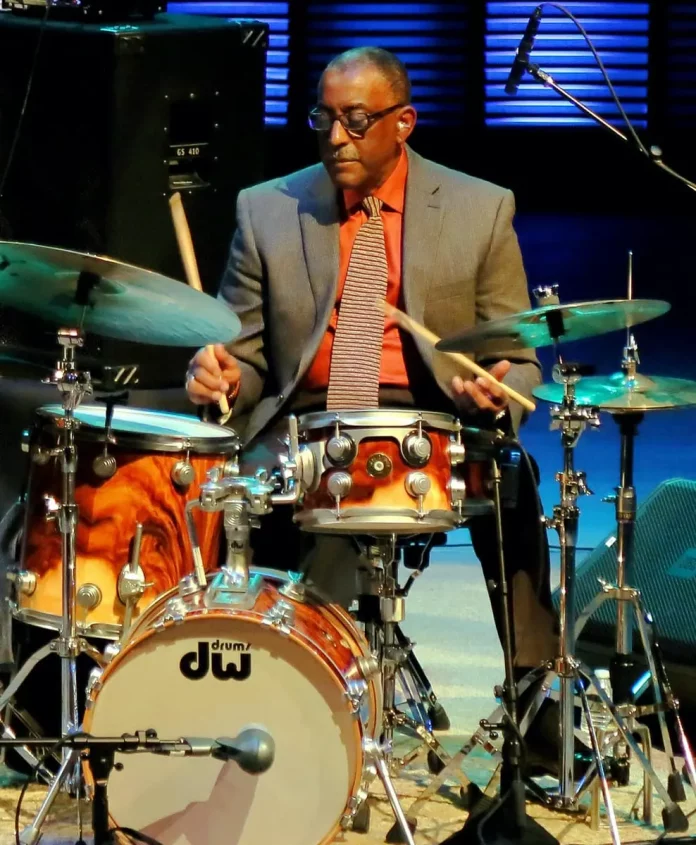

And speaking of Nat, his Live At Memory Lane album is as good a way as any to appreciate the McCurdy drum craft. It’s basically the Adderley quintet with Joe Henderson in place of Cannon, and the percussive nature of the music means the drums really make or break it. Roy makes it. Churning away, slashing and burning, reacting to and influencing the proceedings with edgy vigour, he dominates without overpowering the mix, providing a master class in supportive yet purposeful drumming. A lesser sticksman would be lost in this musical maelstrom, but Roy navigates the stormy waters deftly.

The versatility of this combo was remarkable. When I expressed surprise that Cannon seemed to be playing outside at times on Live In Seattle, McCurdy had this to say: “We had our own personality, so there was a lot of free jazz going on at that time, and Cannon, he liked some of those things that he heard, so he incorporated that into some of the things that we played. Some of the tunes . . . didn’t have any names, because they were just tunes that we’d start playing free without any heads or anything. So we were into that as well as all kinds of things . . . jazz, blues, we did a lot of funk stuff, and we did some free stuff, so we had a lot of different things that we were interested in.”

‘We were one of the first bands to use the electronic piano and the electric bass. Then later on Herbie and Chick and all those guys came into it’

Next I asked how important the Adderleys and Zawinul were to the development of fusion. “Well, I think it was very important because when we started off playing some acoustic things and going into the electric things, Joe was playing the Wurlitzer piano and then the Rhodes piano. We were experimenting with not only soul things, we were experimenting with the other types of music too, and Joe was writing all these tunes that he was kind of leading up to him when he was leaving to go with Weather Report. The fusion thing was very much a part of us at that time, a part of what we were playing. We were playing our regular things and playing a lot of the fusion stuff, too.”

I wondered if the band discussed these changes, or if it just evolved. “No, it was just evolving at that time, that and the soul thing was evolving at the same time. We were playing that kind of music [pre-fusion style], then we were playing things like Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! and Why Am I Treated So Bad, and all those kind of things. And then all this electronics stuff came out of that. We were one of the first bands to play that and to use the electronic piano and the electric bass. Then later on Herbie and Chick and all those guys came into it.”

It all ended with a bolt from the blue in July 1975. Roy retains a clear memory of the fateful day: “He had a stroke while we were talking. We were getting ready to have breakfast, and just out of nowhere, the stroke came. It was in the motel we were staying.” Acting fast, his muscular frame well toned by regular gym workouts, McCurdy deposited the overweight sax man into a car. “We were in one car [taking Adderley to hospital], and on the way, we got hit by another car.” They managed to get him into an undamaged vehicle that arrived safely at the hospital, but the stricken sax giant never recovered. Julian “Cannonball” Adderley died four weeks after the stroke, aged 46.

Cannonball’s passing marked the end of McCurdy’s extended tenures with name instrumental bands, but the start of the same with singers, including 31 years with Nancy Wilson (1980-2011). His versatility ensured success as a session drummer, and from the mid-70s through the 90s, there were record dates with Count Basie, Benny Carter, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Kenny Rankin, Shorty Rogers and Bud Shank and others.

He also developed a reputation as an instructor, giving back to young hopefuls in ways that were unavailable to him when he was first coming up. As adjunct instructor at the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music, he teaches private lessons and occasional master classes in jazz percussion to this day. And though the pandemic had curtailed opportunities to perform, the scene has largely recovered. Just recently, McCurdy recorded a live date that will be available on LP and CD. Featured in his band are a strong front line of Ralph Moore (ts), Eddie Henderson (t) and Andrew Speight (as). And this May (2022), McCurdy was pleased to be inducted into the Rochester Music Hall of Fame, a well-deserved honour. Finally, this busy musician is also hard at work on his highly anticipated autobiography.

Despite decades of accomplishment, McCurdy remains less known than the drummers mentioned at the start of this article. Could his relative invisibility be partly due to his professionalism, his healthy living and eschewing of drugs and other excesses that led many others to untimely ends that nevertheless accorded them varying degrees of notoriety? And while tarnish only adds to the legendary status of some, respectability may not always inspire headlines, sad as that commentary is on the foibles of society. But his clean, stellar track record ensures Roy McCurdy has earned his place among the elite drummers of modern jazz. It’s a reputation he continues to burnish as he approaches his 86th year.

How great is that?

See part one of Roy McCurdy: drumming royalty