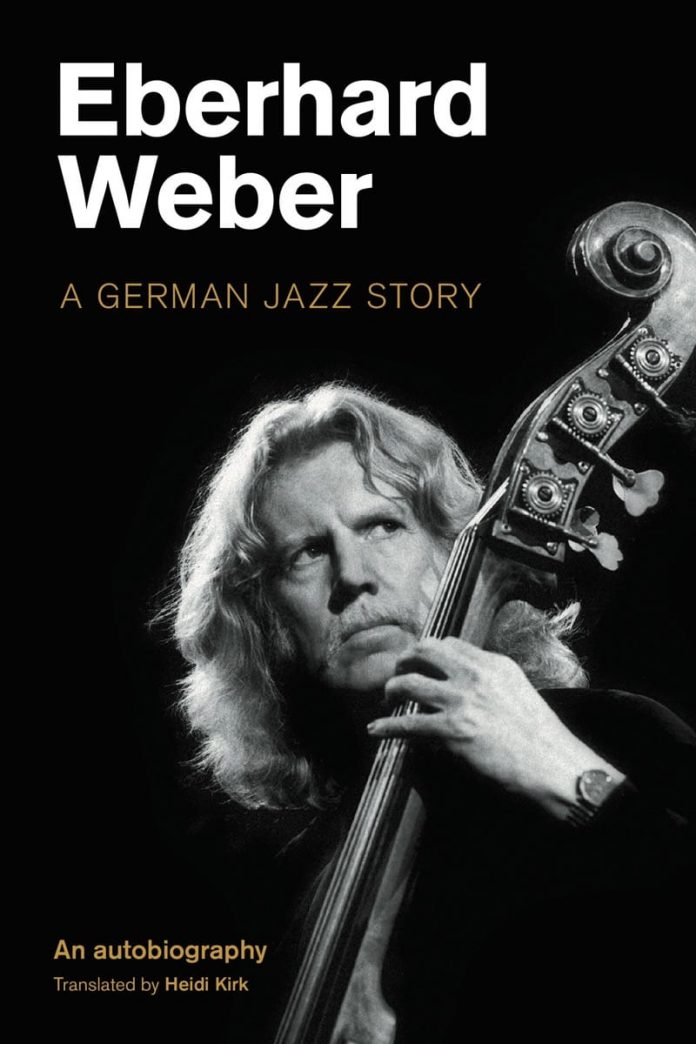

This is a characterful and consistently entertaining, even compulsive, read. Translator Heidi Kirk has done a fine job in bringing over into English the no-nonsense cadences and dry humour of Weber’s Résumé: Eine deutsche Jazz-Geschichte (sagas. edition 2015). The book is handsomely produced, with the pleasing range of (mostly photographic) illustrations having more clarity or “punch” to them than in the German edition. As there, a discography details Weber’s work on ECM as both leader and guest.

However: while the discography has been brought up to date – with the addition of the 2021 ECM release of a 1994 solo concert in Avignon that is Once Upon A Time – there is still no treatment of the considerable body of Weber’s work to be found on other labels. This is as unfortunate as Weber’s suggestion in the text (p 53) that the ground-breaking Dream Talk he made in 1964 with Wolfgang Dauner (p) and Fred Braceful (d) “isn’t available anymore”. In fact, it it has been reissued in both CD and LP formats. Weber’s early work for MPS includes excellent sessions with, e.g., Hampton Hawes, Stéphane Grappelli, Joe Pass and Monty Alexander while his latter-day non-ECM work ranges from Old Friends with the German All Stars, including Klaus Doldinger and Albert Mangelsdorff, to such Eastern-inflected sessions as Percussion Orchestra Meets Phong Lan Orchestra Hanoi with Christy Doran and Reto Weber and Crossing The Bridges with Chico Freeman and the Ustad Shafquat Ali Khan Group. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg . . .

Miles Davis is his cornerstone, contrasted with what Weber sees as the ‘hectic industriousness’ of many young musicians today, shaping a world where ‘everything sounds the same’

The only quibble I have with Kirk’s excellent translation concerns the final lines of the book, where Weber says: “I can’t play the bass. But I know how it’s done!” A while ago he suggested the following to me, which I prefer: “I can’t play the bass. But I know how to handle it!” These simple words point to one of the key themes here – Weber’s belief that improvisation is the heart of jazz and that, rather than being an exercise in the pursuit of perfection “jazz is a constant creative process [.. where ..] individuality counts more than technical perfection”. Here Miles Davis is his cornerstone, contrasted with what Weber sees as the “hectic industriousness” of many young musicians today, shaping a world where “everything sounds the same”.

Following a short Prelude and an initial chapter focused on the stroke which ended his playing career in April 2007, Weber’s story is organised chronologically, but with plenty of room for many a thoughtful and provocative aside. Aspects of group dynamics, touring logistics (and insanities!), personal and stage sound and the interaction of performer and audience are treated with the sort of insight that only comes with a lifetime’s experience. Throughout, Weber is not afraid to ask difficult questions of himself and the reader: questions concerning personal taste and development, success and failure, the nature of jazz, and matters of quality in both acoustic and electronic sound, jazz and classical music.

As one might infer from his music, there is a substantial vein of tenderness in Weber. However, highly intelligent man that he is, Weber has never been one to suffer fools gladly. His demolition (pp 61-70) of the various absurdities of the hard-core “Free Jazz” ideology of late 1960s Germany is perhaps the highlight of the book. Here are some further indicative passages, aimed at the banality of candle or cellphone-lit pop concerts and restaurant muzak, the poverty of musical education in (German) schools today and the contemporary plethora of broadcast music: “I, for my part, go to concerts to listen and to restaurants to eat […] Miseducated … how can one not fall prey to the mass hypnosis of the rock and pop industries? […] My breakfast? I enjoy it in silence… Silence is wonderful – as a musician, you have to try hard to top it.”

Many of the details of Weber’s career will be familiar to the aficionado: the influence of the classical chamber music concerts he heard at home at a very early age, the years as (practically) house bassist for MPS, his various sojourns with Wolfgang Dauner, Dave Pike, Volker Kriegel and The United Jazz + Rock Ensemble and, of course, the glorious years when, following his breakthrough The Colours of Chloë for ECM, he toured and recorded with Gary Burton and led his acclaimed Colours quartet, before becoming a key member of the Jan Garbarek Group for a quarter of a century or so – while also developing a fêted solo concert profile (and appearing on a fair few Kate Bush recordings).

I would imagine that even an aficionado might be a touch taken aback by Weber’s revelations concerning the early impact on him of George Shearing’s Lullaby Of Birdland, Paul Desmond and Dave Brubeck, and, especially, the Oscar Peterson Trio with Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen (pp 33 & 52-53). All such underlines the richness of an autobiography which deserves the widest possible readership.

Eberhard Weber: A German Jazz Story. An autobiography. (Translated by Heidi Kirk). Equinox, 182pp with 37 b&w illustrations, discography & index, hb, £25. ISBN 9781800500822