The provenance of this bass sax-sized volume is most unusual. Forty years ago Dutchman Tom Faber, drawn to Rollini by the records on which he appeared, began collecting information about him and eventually to track down members of his family and those who had known him. This was a rapidly narrowing field, since the multi-instrumentalist had died long before, on 15 May 1956.

Rollini is almost exclusively remembered for his role in defining the use of the bass sax, despite the fact that he was a piano virtuoso who gave concerts when he was a small child and that, during the 30s, his vibraphone work became his main source of income and remained so for the rest of his days in music.

…who could ever forget those honks from a testerone-filled goose that both added to and diverted from the genius of Bix’s cornet on the latter’s records of Royal Garden Blues, Jazz Me Blues and the others where Mr Rollini’s horn could have anchored an aircraft carrier?

But who could ever forget those honks from a testerone-filled goose that both added to and diverted from the genius of Bix’s cornet on the latter’s records of Royal Garden Blues, Jazz Me Blues and the others where Mr Rollini’s horn could have anchored an aircraft carrier? Few attempted to master the cumbersome beast (Min Liebrook and Joe Rushton, miles behind, were probably his best-known followers), yet the athletic Rollini could make it dance. He was equally adept at poking a rhythm section along and coming out front to solo with fluent eloquence.

It’s amazing that van Delden has been able to create such a fine book, faced with so many handicaps, not least of which is to have to devote 90 pages to the California Ramblers, notorious as being jazz minimalists. But I don’t want to put you off. With his information to hand and good style, the author makes those pages as interesting as is the rest of the book.

One might have thought that the bass saxophone was a rare as well as an obscure instrument. That’s not quite true. Those who hoped to copy Rollini seem to have little trouble in finding one, and he had four or five, buying his first one in 1922. They were all made by Conn. He used a baritone mouthpiece instead of the one designed for his instrument. Interestingly, both Harry Carney and Gerry Mulligan cited him as an influence in their playing. Those weren’t his only modifications – he had a silver 50-cent piece welded under the octave key to give it firmness and used piano wire as a spring on his high D key, claiming that otherwise the key would open slightly and cause a leak. In such surroundings a leak might have equated to an iceberg and the Titanic.

There’s much of interest too in the section on Adrian’s two years in London with the genial Fred Elizalde and his band. Shortly after Rollini left, Elizalde’s work for the band collapsed and he returned to Spain where he had success as a composer. Rollini returned to the States to live in Florida where he gave up jazz for a long period.

He seems to have been an amiable fellow who would play in anybody’s band no matter how amateur, and he was always prepared, with remarkable generosity, to lend out one of his horns. He invented several red-hot fountain pens, which were small variants on the clarinet, and was similarly agile in playing those.

There are several collections of his work that haved appeared on CD – Swing Low on Affinity, and others on Timeless, Retrieval and Jazz Oracle, none of which I’ve heard, and Bouncin’ In Rhythm on Topaz TPZ 1027 where inferior sound quality loses the magical presence of the big horn.

So, when you listen to Adrian alongside this absorbing book, it’s best to go for the Bix-Trumbauer and Venuti-Langs, the sparse assemblage of which are on a couple of Mosaics if you’re lucky enough to have them.

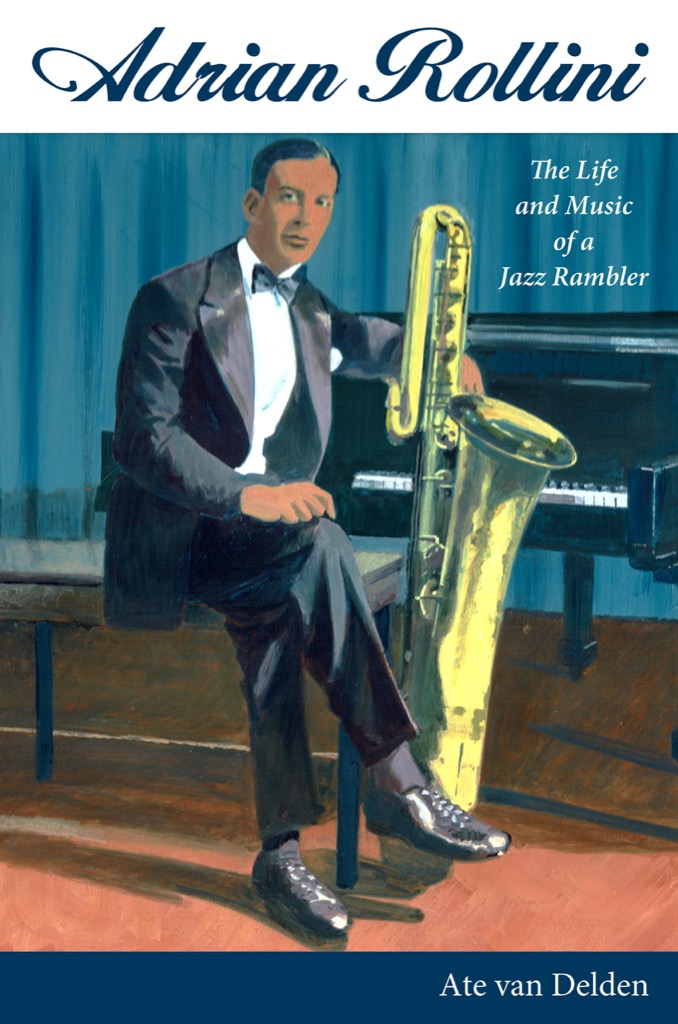

Adrian Rollini: The Life And Music Of A Jazz Rambler. By Ate van Delden, University Press Of Mississippi, pb, 507pp, £34.50. ISBN 97814968252162