Johnny Hodges died in 1970, nearly half a century ago and it’s rather amazing that until now there has been no book devoted entirely to this remarkable musician whose significance in the history of jazz saxophone playing is so great. Here at last is the story of Hodges and I’m glad to say that I can welcome it wholeheartedly. To write a book worthy of such a subject two things were required: a deep and responsive understanding of the greatness of the artist and a willingness to undertake lengthy and detailed research into what could be learned now about a man who died so long ago.

…clear admiration of Hodges is complemented by impressively extensive research, demonstrated by a bibliography with almost 80 entries and unobtrusively numbered notes for references which total just under a thousand

Con Chapman’s appreciation of his subject can be sensed in the three chapters entitled “His Tone”, “The Quality Of Song” and “The Blues”. Here’s an example of his excellent prose: “Like the man playing the reed instrument in the jungle of Henri Rousseau’s painting The Dream, Hodges provided an erotic element to the dense vegetation of the Miley-Ellington sound”. Later, challenging accusations of sentimentality, he writes “Hodges was a dispassionate artist at his easel who expressed deeply felt emotions through the use of tone and colors, not flashy effects”. This clear admiration of Hodges is complemented by impressively extensive research, demonstrated by a bibliography with almost 80 entries and unobtrusively numbered notes for references which total just under a thousand. That might suggest a pedantically scholarly approach but nothing could be further from the truth. Although the book follows a broadly chronological outline, with many details of the early years which were new to me, there are welcome digressions in chapters headed “Women And Children”, “Food And Drink” and “The Coming Of Bird”. I had to look up “Lagomorphology”, a chapter on Hodges as man rather than musician, and found that it means the study of conies, hares and, of course, rabbits. (The Internet informs us that Mr. Chapman has produced plenty of humorous literature as well as writings on jazz.)

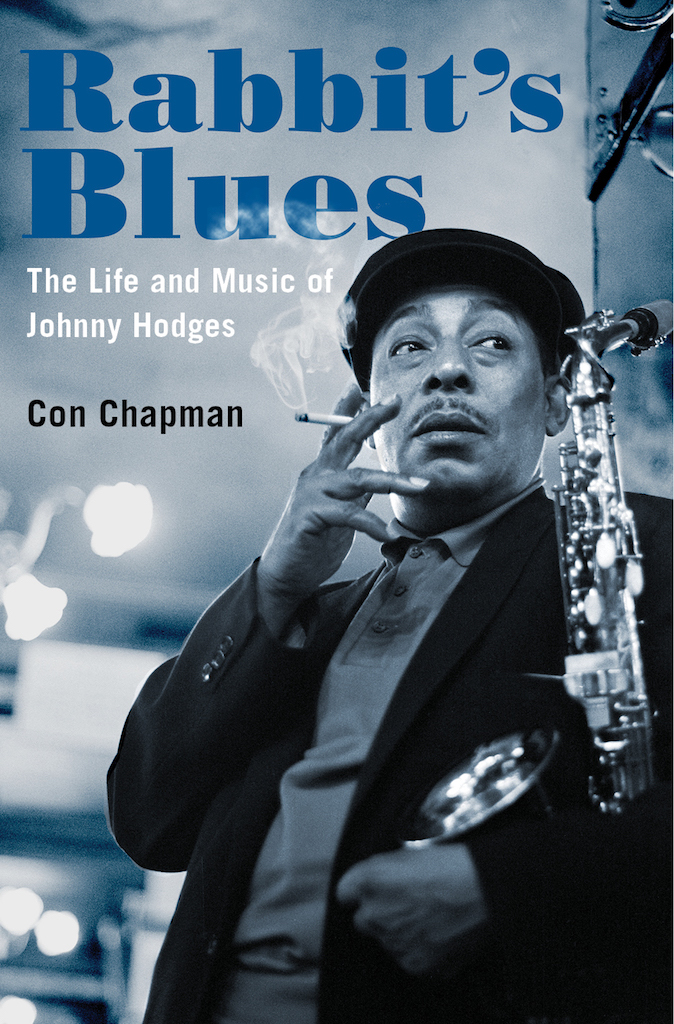

In covering the recorded legacy of Hodges the author has wisely given only selective attention to the recordings with Ellington, already written about extensively, and has concentrated more on the recordings which are, as he says, “outside the Ellington constellation” and which in later years offered significantly more of Hodges than could be heard on the Ellington releases. There’s far more in the book that’s worthy of appreciative comment than this review allows space for, but I should mention the 16 pages of photographs. These include Hodges in action as well as relaxing, a moving shot of his wife at his funeral and a mural showing Ellington with Hodges which is painted on the side of the house where the latter grew up. (I’ll also single out something of particular interest to myself. While considering Hodges as a person, the author examines what Hodges had in common with Lester Young, both as man and musician. This is a topic worth exploring and I would suggest that Young came musically closest to Hodges towards the end of his life, in particular on his floating tenor solos from the 1958 album called Laughin’ To Keep From Cryin’.)

Con Chapman didn’t write this book because Con is short for Cornelius – a name also given to Johnny Hodges at birth though soon dispensed with. But Con obviously has something far more significant than that in common with Johnny: a belief that if something’s worth doing it’s worth doing impeccably. And his commitment to producing a book worthy of his subject is clear on every page.

Rabbit’s Blues – The Life And Music Of Johnny Hodges. By Con Chapman, Oxford University Press, hb, 175pp, 47pp notes, bibliography and index, 16pp photographs. ISBN 978-0-19-065390-3.

The editor inadvertently commissioned two reviews of this book, so here’s a second opinion by Steve Voce:

“Little of his personality emerged from the cocoon of his imperturbability”. Rex Stewart, speaking here, never lost the manner of a Victorian parliamentarian. But he was right, and Johnny kept his thoughts to himself, giving Mr Chapman a double handicap because Rabbit had also been gone for almost half a century before this book was written. Understandably the book is quite short as a result – 175 pages of main text and 50 pages of bibliography and notes. Careless of baffling the reader, the author describes Johnny’s face as “”leporine” (I looked it up for you – “hare-like”). He’s also given to a touch of Rex’s Victoriana as in “The date on which Hodges changed his residence from Boston to New York is not susceptible to precise determination… Until he made the move Hodges was a peripatetic practitioner for some time…” “We don’t know when he moved” would have done.

Hodges was a passionate soloist who created beautiful improvisations at the highest level. You wouldn’t deduce that from his conversation, which was friendly enough but terse.

On the face of it such a giant of jazz cried out for a book about him. But because he never did anything unusual when his horn was not to his lips the author’s job is much the more difficult. Inevitably Mr Chapman has rounded up all the material he can find, and the book is filled with quotes from everyone, your current reviewer not excluded.

The author can be indecisive – of Flaming Youth he writes “According to one source Hodges plays both alto and soprano on the song: according to another only alto”. I took the trouble to listen to both takes of Flaming Youth and can tell Mr Chapman that Johnny plays both horns on each take (Johnny gave up soprano in 1940 after Duke refused to pay him extra for doubling).

Chapter 7 is sometimes tawdry and unkind. “It is not surprising that Johnny Hodges … would favour women from the night life; he would marry and have children by two, carry on a youthful affair and have a daughter by a third and have at least one overseas fling that produced another child”.

There’s considerable speculation in these pages. I found some distasteful as in “The possibility that Ellington ever paid for sex cannot be ruled out entirely…”

No matter where the details come from, we need reminding again of much of the material. Sidney Bechet, for instance, was in the Ellington band before Hodges ever joined. And before joining Duke Johnny was in Bechet’s own band, where he was taken under the wing. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me”, said Hodges. “He would tell me to learn this and learn that”. The association between the two men was much closer than history recalls. When, in 1951, the French trumpeter Pierre Merlin told Sidney that he was delighted to hear him play the Johnny Hodges chorus from Ellington’s recording of The Sheik Of Araby Bechet snapped “He stole that from me!”

The reader must make up his own mind about the book’s contents, but there is no doubt that it is both useful and absorbing to have so much detail of Johnny’s life collected here, and I’m sure most mainstream jazz enthusiasts would find it rewarding to read. Johnny needed a book about him.