News arrives via Joey DeFrancesco courtesy of Tom Fletcher of the death of guitarist Pat Martino. His style is well framed in a YouTube video with DeFrancesco and John Scofield in Umbria in 2002.

To mark his passing, here’s a 2001 interview Mark Gilbert did with him, first published in Jazz Journal in July 2013.

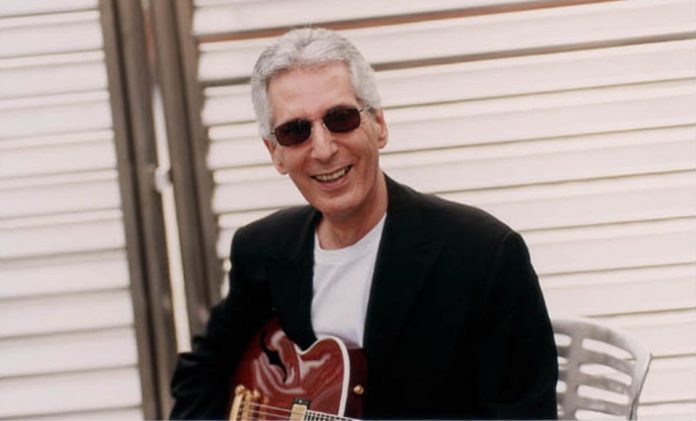

Pat Martino: precision guitar

Widely reported for his recovery from a near-fatal 1980 aneurysm that caused severe memory loss, by 1987 Pat Martino had relearned enough to record The Return for Muse. A few years later his powers seemed fully restored. In this unpublished 2001 interview with Mark Gilbert, the slightly built Martino, once dubbed for his lean, dapper appearance the Lee Van Cleef of the guitar, touches on influences, techniques and technology, his answers delivered in a surprisingly grave bass voice with an almost biblical syntax that reflects the precision and detail of his guitar playing.

Have you done anything other than music?

“No, I never have. I’ve been in this business 45 years. I began in 1956. I was 12 years old, but I had fiddled with my father’s instrument for quite a number of years prior to that, since the age of three. I didn’t get serious about committing myself to it until 1955-1956.”

What was the motivation to play?

“That’s a very funny thing, you know. I really believe that it had a great deal to do with childhood and wanting to participate with the adults that surrounded me at that time. Being an only child, it seemed to me that it was a significant achievement to be able to be of interest to an adult intellect. It became so serious that I began performing with various generation gaps and at the age of 12 performing with 30-year-old musicians.”

Were you playing jazz at that time?

“Not yet. I began playing with slightly older players and artists like Frankie Avalon and Bobby Rydell and some of the first members of the rock & roll fraternity in the United States. I enjoyed that very much, and then suddenly I happened to win a contest. Well, actually I came in second place – I lost the contest to an eight-year-old ballerina. The prize table was full of 33⅓ vinyl albums, each with a very colourful cover and there was just one that caught my eye and that was an album on Columbia Records that was by Donald Byrd and Gigi Gryce. Because it was just a black and white cover it stood forward amongst all the others and I selected that as my prize. And that’s when my interest in jazz began.”

Was there a guitar player on this record?

“No. In fact I wanted to be a horn player, a trumpet player, but my father advised me not to do so because of my lips. He said this would be terrible, you would have a very crude kiss.”

Were there guitar players who influenced you fairly early on?

“My first influences were coming from my father. My father was a guitar buff, and he really enjoyed such artists as Eddie Lang and Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. I felt surrounded by these things, never understanding them until I heard Donald Byrd and Gigi Gryce. That began my interest in guitar and from that I went upward toward more recent – at that time – artists such as Johnny Smith.

“Wes Montgomery – that became a personal affair, because Wes and I became very close friends in the early to mid 60s. But there were so many guitar players at that time that were just prolific. It was flourishing immensely. There was Grant Green and there was Kenny Burrell and Joe Pass, Howard Roberts, Tal Farlow, Mundell Lowe – so many great players. And in Philadelphia, where I grew up, it seemed that there was a core in terms of influence and interest in that instrument.”

Your mature style, apparent in the mid 70s on such records as Consciousness (1974), seems some distance from those players. Do you know where it comes from?

“I think so. Of course my initial years were highly influenced by Wes, and specifically for a very earthy contour that really matched the culture at the time in Harlem. In terms of precision and my need for almost a Virgo-type of representation of everything, my influences came from Johnny Smith, who was so romantic and at the same time so precise.

“My style at any given point from 1968 onward I think really was affected by an interest in intervallic divisions of the instrument and how its proportions seemingly to me at that time were quite different than the piano. And due to the nature of the instrument itself, the mechanism itself, it led me far from a scalar approach as well as the modal approach that many guitarists are dependent on; the fluctuations that come from that I find are extremely pianistic, based upon the seven white keys and the five black keys. Whereas on the guitar I found that these things were not automatic. The piano is horizontal and therefore it functioned only from the east and the west. There was no north and south mechanically built into the machine itself, where the guitar provided this. It opened to a higher dimension, and this really excited me. I think everything that followed thereafter had a great deal to do with the proportions of the instrument.”

You had left Philadelphia at 15, perhaps in some sort of rebellion?

“At that time I was studying with Dennis Sandole in Philadelphia and I wasn’t quite tuned into his procedures. On the other hand I found it very interesting studying him as a human being and his surroundings. It was almost like studying Van Gogh – studying what was on the wall and what was in the room and the position of things and the quality of how much dust was on this or that. These things really affected my interest in social interaction, so much so that at the age of 15 I left home. I ran away and went to Harlem, New York City, and I grew up there from that point forward in the jazz community. I think that time had a great deal to do with social interaction more than it had to do with music, and it still does. I’ve always seen music as secondary to what it leads an individual toward. I see music along with the guitar merely as instrumental, almost like a fork or a spoon.”

You seem, generally speaking, to favour harmonically intense situations.

“I love the minor much more than the major, maybe because in my earlier years teachers had a great deal to say about the major scale and the melodic minor that came from it and the natural minor that came from it, and of course all of the modes. And anything that had to do with the scalar approach to me seemed to be a little more mechanical than expressive. The greatest example of that was Wes Montgomery, who knew nothing about scales or modes or curriculum. It came from his heart.”

It’s been said that your harmonic conception is based on putting everything into the minor. How does that work?

“Well, if I was to see on the guitar a C major 7th chord with the root being C, the fifth being G, the seventh being B and the E being on top of it, and if I look at the three tones on the top cluster, I see there’s a polychord. I see E minor over C. Accordingly, if I were to see an A7#5b9 chord, that chord would contain in this particular voicing, the root on the bottom, then the dominant seventh, being the G, the third being the C#, the sharp fifth being the F and the flatted ninth being the Bb. If I were to take the root and dominant seventh out of that, all that is left is a Bb minor triad on the top. So that’s where I might start from. That seems to be logical to me, primarily because it’s so visible on the guitar.”

How would you work with that minor chord in an improvisation? Decorate it or arpeggiate those particular tones?

“I think I take advantage of experience. Les Paul said to me, at the age of 13 years: ‘You have the ability to play many notes and let me advise you to do this: those things that you play that seemingly cause no reaction, get rid of those things. Those things that do cause reaction, keep them. And if you have seven of these things that continuously and repetitively cause similar reaction, this shall be your identity.’ You will then have the power to be controllable with regards to social implications. So this I began to do at a very early age. When I think of a Bb minor seventh chord that I used to play in the earlier years with Sonny Stitt and Gene Ammons and it had effect on my surroundings, and I see that A7#5b9 with the strongest identity being the Bb minor triad on the top I then have the option of playing all of the things that over a period of 45 years have been associated for me with Bb minor. That opens up endless possibilities.”

How do you get to play as precisely as you do?

“I believe that the easiest way of having a need to be as precise as possible is being disappointed whensoever you’re not. And to me there’s nothing more disappointing than the lack of precision. And of course that comes about naturally for all of us at different times. No matter what we do, there’s times when our penmanship is flowing with grace and fluidity and there are times when possibly we slept in the wrong position and that graciousness, that flow, is hampered.”

Is it true that when you had your unfortunate illness you forgot how to play the guitar completely?

“Yes, that is true. After the operation, the neurosurgery itself – but let me clear that I certainly don’t consider it unfortunate due to the fact that it has produced temperance, has produced a greater awareness of self-esteem, has produced so many things in terms of endurance and quality. It’s produced optimism on my behalf, a healing from internal properties. So it’s hard for me to see this as unfortunate. I do think willpower has a great deal to do with this, and that’s something that is out of our control with regards to individual character.”

Tell us about your guitar. You like quite heavy strings, don’t you?

“Yes I do. Generally I use two different types of gauges, depending upon the instrument itself and depending upon the environment I’m going into with it. The lightest gauging that I use is from the top 15, 17, 24, 36, 42, 52. But I normally use 16, 18, 26, 36, 48, 58, depending on the humidity and the temperance in terms of the environment I’m going into, from one point of a tour to another.”

You could adjust the neck to compensate?

“Oh yes, I do. I really do think it’s a necessity for a guitarist to understand the nature of the machine itself and to be able to readjust when needed, primarily because to interrupt one’s intimate relationship with the instrument by letting a stranger do it is sometimes a foolish thing to do. The instrument then becomes inhibited with the personality of the third party.”

Those are heavy strings – some players will be surprised to hear you can play so fast with such heavy gauges.

“Well, my right hand is uncontrollable and my left hand is fully intellectual. So if it were not for heavy strings I’d break strings due to lack of control with aggressive attack. I’ve never given thought to that and the easiest way of avoiding the commitment to stabilise it with a system has been to use heavy strings and protect it that way and let the freedom abound.”

Could you name off the top of your head five or six albums that are favourites?

“It’s a funny thing. It’s a difficult condition for me to answer. Because of the neurosurgery it’s difficult for me to retain information such as names, dates, titles and details. When I listen to something I love what I remember is the moment that I loved. It’s difficult for me to remember all of the names. Of course I can in a general context point out certain things but I don’t think it would be fair. It’s like homework, like memorising the history, the liner notes of things. I’m more interested in essence of the product itself, in this particular case being music. I love the experience, the audio of it as opposed to the visual context. I just yesterday listened to the first cut on a Branford Marsalis album called Contemporary Jazz and I truly enjoyed that. That particular cut was exquisite.”

* * * * * *

Pat has been reluctant to discuss the work of other players, declining to participate in a blindfold test with this writer some years ago on the grounds he “went through that experience with Leonard Feather” and was not about to repeat it. However, he does have his blindspots: Scott Henderson, reviewed on page 28, once reported in all good humour that his work drew from Martino the observation “That is not guitar playing!” This despite Martino’s own 70s work often being construed as jazz-rock.