In the mid-1950s the US State Department made the sending of jazz “ambassadors” to countries around the world (particularly the Soviet Union) its pet project. Given that jazz was still regarded by conservative Americans as a degenerate art fuelled by sex and drugs, and that its leading exponents were black, this was surprising. But although African Americans at home were subject to discrimination, segregation and violence, such jazz luminaries as Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Stan Getz and Dave Brubeck were sent abroad with instructions to ignore (or refute) these practices. They were not prepared to do this.

The topic has been ably covered by Penny M. Von Eschen (Satchmo Blows Up The World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War, 2004) and more recently by Ricky Riccardi (What a Wonderful World: The Magic Of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years, 2011). Now Keith Hatschek has focused on a project initiated by Iola Brubeck in 1956 to present a “musical” (which she hoped would be performed on Broadway) starring her husband, Louis Armstrong, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross (later replaced by Yolande Bavan) and a young Carmen McCrae. It would expose American hypocrisy on racial issues, and celebrate the courage and determination of jazz musicians to set the record straight.

The Brubecks were anxious to get Armstrong (who had received rapturous receptions on his African tours) to be the main figure in their projected musical (set in an imaginary African country). He readily accepted the starring role, and told friends: “The Brubecks have written me an opera and I’m going to do it.” Brubeck recalled in 2003: “When we put the idea to Louis for The Real Ambassadors no one thought that he would do a musical at his age.”

Dave and Iola composed 15 songs for the projected show, including Remember Who You Are – a parody on State Department briefings to jazz artists about to depart on “ambassadorial” duties abroad. A sample of a few verses (with a decidedly Gilbert and Sullivan flavour) advised:

Remember who you are and what you represent

Never face a problem, always circumvent

Stay away from issues. Be discreet.

Jelly Roll and Basie helped us to invent

A weapon that no other nation has,

Especially the Russians can’t claim jazz.

Dave Brubeck persuaded Columbia (his own label) to cut a demo album at a cost of over $10,000. In rehearsals, Louis sang the song They Say I Look Like God – but in an aside to fellow performers joked: “But God don’t look like me.” Yet he was undoubtedly moved when singing the banal lyrics, to the extent that he had his studio audience in tears. Nine months after the conclusion of the studio sessions (and four weeks before its premiere at the Monterey Jazz Festival), Columbia released the LP.

In his sleeve notes Gilbert Millstein explained: “The Real Ambassadors grew out of the desire of Dave Brubeck and his wife, Iola, a writer, to accomplish two things: to crystallize in music, lyrics and book the humanity of jazz and the musicians who make it … and to offer the creation as a tribute to Louis Armstrong as the principal exemplar of their sentiments.” Yet without Iona’s explanatory narration (which she provided at Monterey) the separate songs were discursive and/or unintelligible. Moreover, the juxtaposition of Armstrong’s All-Stars “traditional” jazz” with Brubeck’s “cooler” sounds (from opposite ends of the stage) were not readily endorsed by an already divided jazz-listening fraternity.

Hatschek concedes that the story line lacked sufficient substance to be performed on stage, while Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser opposed every attempt to have it transferred to Broadway or London as Louis was his cash cow only when on the road. Commercial sales of the LP were poor, but improved slightly when it was reissued in 1994 with four additional tracks, one of which was You Swing, Baby, and an Armstrong/McRae duet set to the melody of Brubeck’s composition The Duke.

Hatschek himself has remained active in promoting performances of The Real Ambassadors, including a 2013 performance in Detroit, and a year later, one at Jazz at Lincoln Centre – but sadly after the deaths of Dave and Iola. In his programme notes to the Detroit performance, Will Friedwald wrote that it was “the rare work of art to have grown in stature over the last 50 years … the more one listens, the more amazing it sounds – a jazz song cycle with the flair of Broadway and a sense of social consciousness unique to any musical medium”.

He might have added that songs associated with the civil-rights movement – especially its anthem We Shall Overcome – were more profound and understandable condemnations of what the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal writing in 1944, called An American Dilemma – its (continuing) obsession with race. Again, Charles Mingus’s Fables Of Faubus indicted the governor of Arkansas – whom Armstrong reportedly called “an uneducated plough boy” (but actually “a motherfucker”) – for blocking the entrance of black pupils to Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957.

British critic Peter Clayton asserted that the original LP was “a very strange record, but not by any means a very good one”. It is certainly not a major item in either the Brubeck or Armstrong discographies. Lambert, Hendricks and Ross deliver the tongue-twisting lyrics so fast that they are often unintelligible. By far the most memorable performance is Louis’s vocal rendition of Summer Song, followed by two duets with McRae.

But there is no gainsaying the Brubecks’ commitment to racial equality. Dave (despite the financial loss) would not perform at Southern college venues that refused to accept his African American bassist Eugene Wright. Louis, in his advancing years, spoke out and acted more forcibly on discrimination and segregation. Well-written, impressively researched and often moving, Hatschek’s book is both a work of scholarship and an obvious labour of love.

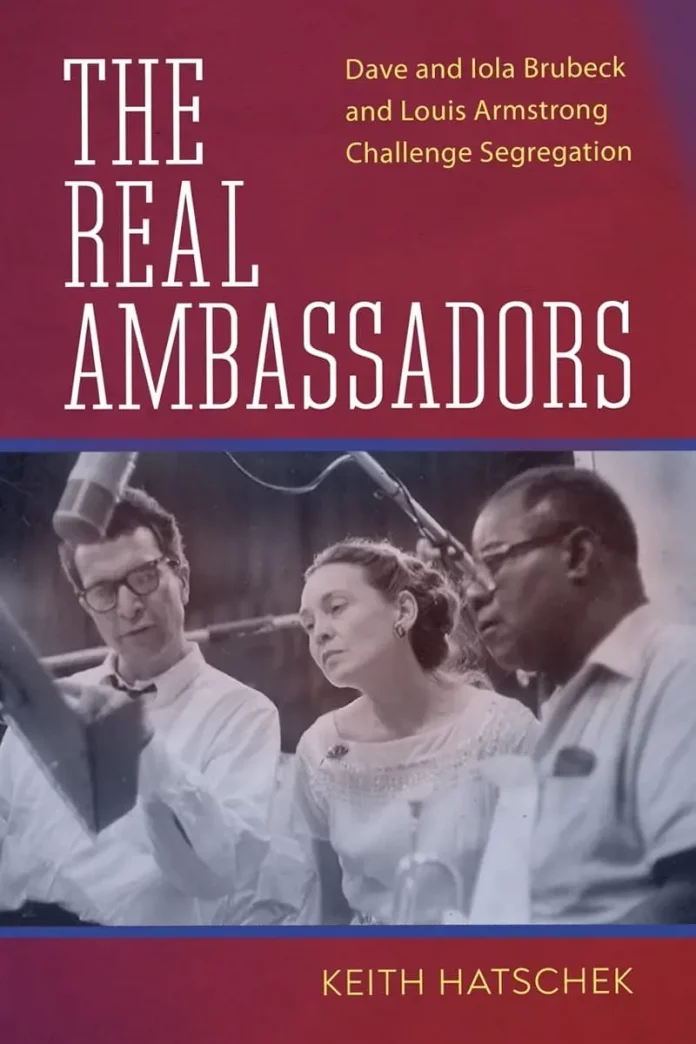

The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Segregation by Keith Hatschek. University of Mississippi Press, 298pp, 29 b&w illustrations. ISBN 978-1-4968-3784-4