“Ubiquitous” is one of the many over-worked adjectives beloved of jazz scribes, but it is nevertheless apt when applied to bassist Paul Chambers. No-one else turns up with greater regularity on American recording sessions, and it is obvious from his very omniprescence that Paul is, together with Ray Brown and Milt Hinton, one of the most sought-after bassists playing today. He has demonstrated that, when used to accompany, the bass can produce patterns of melodic as well as harmonic value, and he is also an accomplished soloist, both argo and pizzicato.

“As a matter of fact”, he told me, “most people are very surprised when they hear what the bass can do, and they say ‘Damn, all I thought it could do is “boom, boom, boom” ‘.”

Paul has, in fact, furnished firmly pulsating backgrounds to a multitude of performances by such as Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Phineas Newborn, Benny Golson and George Wallington, but in spite of his experience he is quite a young man – only twenty-five years old. “I’ve been playing for eleven years, and it bugs me when some people seem to think we’ve only just come on the scene,” he said. “People don’t seem to realise how young some musicians are when they start playing.”

Funnily enough, Paul’s introduction to music was accidental. “This may seem crazy to you”, he grinned, “but when I was in Sixth Grade waiting to go to Junior High, we were all of us kids sitting in a room and the tables were set aside for different subjects. It happened by mistake that I was sitting at the table for music, and that’s how it started. Plus, my mother was very musical.”

And so it was that the young Paul Chambers started playing tuba and baritone sax in the school band. “The school I went to was a Technical High School, and the curriculum took up a whole day in music. That’s why it took a couple more years to graduate. For example, we’d have the first period chamber music, second period full orchestra, the third period was either harmony or counterpoint and rudiments; then came piano and the academic classes.”

‘I used to work a duo on-and-off with Terry Pollard, and you know there’s a lot of people around who say “She’s good, for a girl.” That’s stupid. There are many good women musicians; it bugs me every time I hear that’

The school, Cass Tech, was in Detroit, where Paul had moved at an early age from Pittsburgh, where he was born on April 22nd, 1935. In keeping with Detroit’s record of producing talented musicians, Cass Tech boasted, at one time or another, Doug Watkins, Donald Byrd, Lucky Thompson, Al McKibbon and Barry Harris.

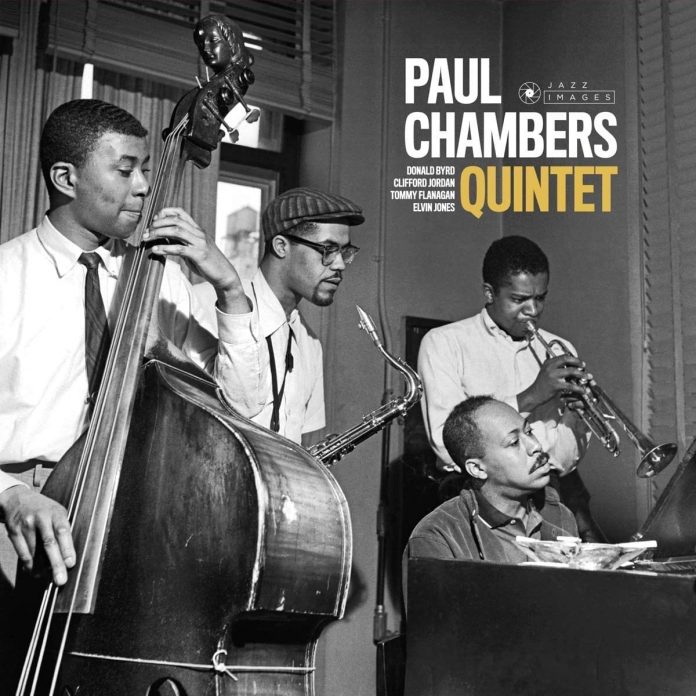

“I used to get together with Doug, Donald and piano player Hugh Larsen between and in rest periods, and we’d play. Donald is a very impish type of person, he’s clownish, but he’s very serious about music, too, and I think he’s pretty original.”

This was two years before Paul came to New York. “I was working at nights with Kenny Burrell. He had a very nice group with Yusef Lateef, and Hendel Butts on drums. Kenny’s making quite a good living now, doing mostly studio work in New York and jazz jobs at night. He used to like to sing, so we had a few arrangements something like the Four Freshmen. I wonder if I could do that now?”

He continued to work with various combos around Detroit: “I used to work a duo on-and-off with Terry Pollard, and you know there’s a lot of people around who say ‘She’s good, for a girl.’ That’s stupid. There are many good women musicians; it bugs me every time I hear that.

“Everybody has dreams of going to New York one day or other, because that’s where you can probably make a reputation. So, I just waited for Paul Quinichette to come along and he took me out of Detroit. I played with him for about eight months, which was good experience. We had Sir Charles on piano, Chink Williams on drums, and a guitar. In those days Paul was drinking quite a lot, but he was a nice cat. The jobs weren’t too plentiful, though, so he had to break up his band – that was in 1954.”

‘There’s some horrible stuff in the Deep South, but funnily enough, every time I get over here, people seem to have a worse picture of it than it really is. I didn’t have any trouble at all’

After the break-up of the group, Paul left with Chink Williams to join Benny Green, who also had Charlie Rouse on tenor. “This was sort of in-between; musically it was very good, but Benny Green had them commercial things going. Like, most of the dates we did were with rock ’n’ roll singers. We did a two-month tour of the South once, and I guess that was the hardest thing I ever did. We haven’t been in the South for quite a while, and I’m not too interested in going again. But it depends. There’s the Deep South and the kind of South-West – Maryland, for example, is on the border, but it’s O.K. There’s some horrible stuff in the Deep South, but funnily enough, every time I get over here, people seem to have a worse picture of it than it really is. I didn’t have any trouble at all.

“After that I went with Joe Roland, a very wonderful cat who plays vibes. He wasn’t quite as big as he should have been because he used to work with George Shearing, messing around, like going to hit and missing – all that baloney. We had a wonderful group down at the Club Bohemia, with George Wellington, for about six months straight. It was wonderful because there was actually no leader and we all could do what we liked. There was Jackie McLean, Don Byrd and Art Taylor. We made some sad records, because they were just trying out that recording scene in the night clubs, then. Oscar Pettiford was musical director at the Bohemia and we used to have a ball. Lots of times we used to get up and play two basses after the show, and sometimes he’d play cello. I took one home a couple of times and when you play it, things come out a little clearer because it’s a smaller instrument.

“As a matter of fact I have some duets I’ve written, a whole book. Richard Davis and I used to get together, too, and play duets, sometimes three times a week. He’s with Sarah, but you can’t really hear him with her, which is a pity because this cat is terrific, man! The Chicago Symphony wanted him, you know. When I first met him he came up and introduced himself, very humble, like, ‘I’m Richard Davis, very pleased to meet you’, but when I heard him play! He’s a very good bass player!

“When I was playing at the Bohemia, Miles used to come down and listen. He was trying to get a band together and that was when I joined him. He probably thought I’d fit with his group, and we had a very wonderful thing, with Red Garland, Coltrane and Philly Joe Jones. That was about 1955, and I’ve been with him ever since.

“I like Miles, you know. People seem to think like he’s a panther or something, when really he is a very nice person. They put more emphasis on his personal life than on his playing. In most interviews, the average person would try to stump you, and Miles probably hasn’t got time for that; like, he’s thinking what he’s got to do. He takes his music seriously, but it’s a serious thing. Just imagine a world without music!

‘I’ve been with Miles a long time, and it’s not all just a gimmick; he’s really like that. Most of the time when he wants to talk about music, people want to talk about everything else. So naturally he gets bugged. I don’t think he’s prejudiced either. It is mostly a joke’

“I’ve been with Miles a long time, and it’s not all just a gimmick; he’s really like that. Most of the time when he wants to talk about music, people want to talk about everything else. So naturally he gets bugged. I don’t think he’s prejudiced either. It is mostly a joke; he couldn’t really feel that way, for he had a white wife for years. People lay too much on all that and enlarge every little thing he says.

“But some of the things people do over there are pretty weird. I remember one time we were taking some people home in the car, and the cops stopped us. They took the girls along to the police station and tried to make them say they’d been raped or something. It’s the same sort of thing happened to Miles outside Birdland. He’d just put a white girl in a cab and I was the only witness. I don’t know where all those people came from. In a few minutes it seemed like there were three hundred or four hundred people there, police cars and all. But that’s America for you.”

It was obvious that Paul is happy with Miles, and unless something radical happens, he will be staying with him for some time. He seems to have few ambitions – a rather slow and lackadaisical fellow, whose six-foot frame is surmounted by a pixieish face. However, beneath the careless exterior is an alert mind which is set to channel the role of the double bass towards further conquests on the rhythmic scene.

“The bass is a very hard instrument to play, both physically and melodically, but when it does come out right it’s very beautiful and that makes it all worthwhile.”