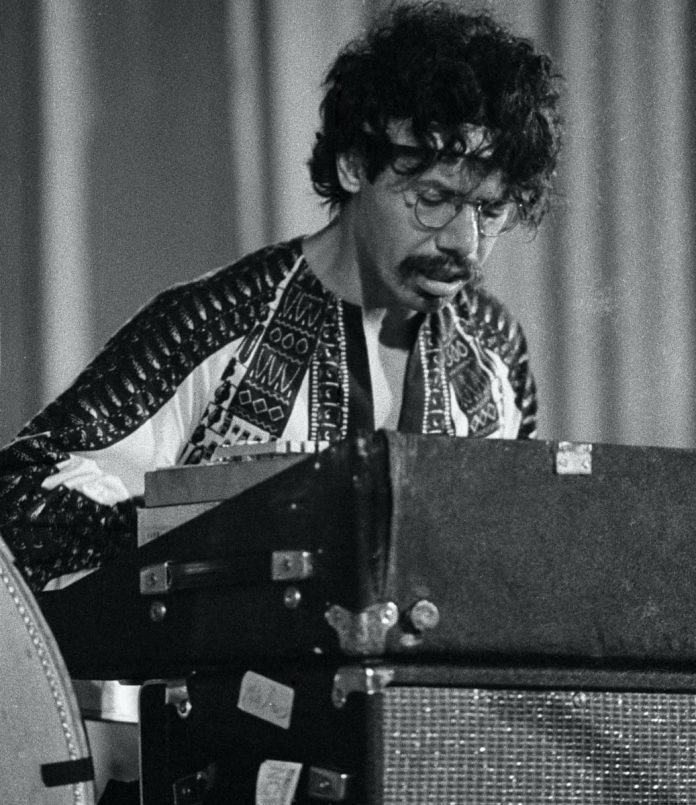

Nearly a year ago the world lost one of its piano greats in McCoy Tyner. Now it has lost another who operated in the same era but in a quite different way. I’d regard Chick as one of the great keyboard players. He used the electro-mechanical Fender Rhodes piano and the synthesizer as much as the acoustic piano – the electric side of his music wasn’t an occasional diversion or experiment. He just made the best use of the range of keyboards available to him at the time. Biographical and critical tributes abound already, so in this piece I won’t repeat much information that you can read elsewhere, and focus instead on the music.

There has been a snobbery among some critics about Corea “diverting” into electric instruments. However, to say someone who worked with great success on the electric and electronic keyboard over decades shouldn’t have done so is like saying that the keyboard innovators of the late classical period (Beethoven, the Romantics and 20th century piano composers) shouldn’t have used that relatively new keyboard instrument of the time – the acoustic grand piano.

Had it not been performed on electric instruments, Got A Match?, one of his many great tunes, would, I’m sure, have been universally hailed in jazz as some kind of masterpiece of its time, linking bebop to J.S.Bach.

A glance over some reliable musical transcriptions of Corea’s playing show that his style (in terms of chord voicing and right-hand lines) doesn’t really change, whether playing acoustic or electric instruments. The execution of the notes – the keyboard touch, would be different on these different instruments, but most of the musical nuts and bolts remained the same. Have you ever tried playing bebop or post-bop right-hand lines on a KX-5 synthesizer controller (a so-called “keytar”)? Well, it’s no mean feat, as it wasn’t really designed to do that, but Chick seemed to do it with ease, and it gave him the opportunity to add a different kind of expression in performance, using modulation (vibrato) and pitch-bending. Thus the language of jazz expands. He was able to make the improvised line stand-out and sound more like a lead instrument. Had it not been performed on electric instruments, Got A Match?, one of his many great tunes, would, I’m sure, have been universally hailed in jazz as some kind of masterpiece of its time, linking bebop to J.S.Bach.

The use of the KX-5 also helped him communicate with live audiences in a more direct and contemporary way. I recall seeing him at the Corn Exchange in Cambridge, which at the time was not renowned for its great acoustic (it was a corn exchange). The audience were sitting in their assigned seats, some distance from the stage, where the sound was at its worst, and he had the good sense (acoustically speaking and in terms of communication) to invite everyone up to the front by the stage to stand through the performance. It was a great example of him being an unusually good communicator in the often taciturn jazz world.

One of the things that made Corea musically unique was being a Latin keyboard player and composer who also happen to play a lot of jazz and some Western classical music. There haven’t been many of those. One example might be Michel Camilo, but, like Tyner in some ways, he’s a piano-only guy, never venturing into electric instruments.

Chick’s compositions were also unique for the time, often with chord progressions of unusual length (he often added an extra two bars to the typical song structure) and a tendency to avoid the tonic at the end of his tunes and chord progressions; the latter became a very common trick amongst many players who followed. His right-hand lines sound distinctive partly due to the use of grace notes, decorating his already melodic lines. Even now, when the “next big thing” comes along in piano, keyboard and composition, it’s pretty common to hear them coming in some way from the Chick direction.

I saw him for the first time at Ronnie Scott’s in London in the mid-80s, when I was a young music student, with the first incarnation of his Elektric Band. It was a bit of a shock after hearing his previous work, but the musical content remained distinctively Chick, despite the change to some instruments and sounds. This was the 80s, so to remain up-to-date and relevant the music had to become tighter in structure and time, and use the newly available technology.

Writing about bop pianist Bud Powell at the time, I asked Chick after the gig what he thought of Bud. He said “He’s a great teacher.” Strip away some other elements and Chick’s right-hand improvised lines have more than a hint of bop – predominantly quaver movement, seemingly weaving around the chords. But at the same time he had the tendency to play patterns in groups of four notes. This probably had more to do with playing over the more open chord structures of the 50s, 60s and onwards, which Bud would never really have encountered.

The last time I saw Chick playing live was again at Ronnie’s, just a few years back. This time he was on piano only, in a trio setting. He sounded like a seasoned master of the instrument, especially in a wonderful selection of piano introductions. His so-called diversions into the electric world clearly hadn’t done him any harm as a pianist.

Chick (Armando Anthony) Corea (born 12 June 1941, died 9 February 2021) leaves a weighty musical footprint, having reached many more listeners than the worlds of jazz, classical and Latin might do individually.