It is one of the paradoxes of today’s music that the more advanced or ‘far out’ styles are not necessarily more difficult to listen to. Indeed several avant-garde players seem to have the ability to communicate to wider audiences than many more conventional men. This is certainly the case with John Surman, whose brilliant baritone playing is now getting the acclaim it deserves all over Europe. And with Dave Holland, John McLaughlin and other worthy locals spreading the good news the other side of the Atlantic it seems that the Americans are beginning to realise that Surman, along with a number of other British jazzmen, has much to offer.

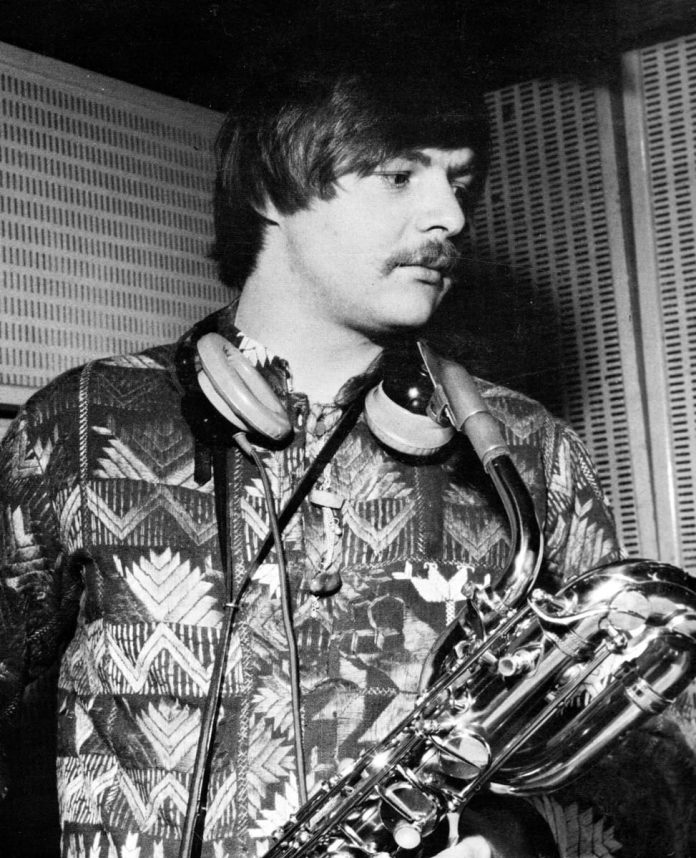

His success comes as no surprise to those of us who have seen him play. Whatever context he appears in, whether leading one of his own groups or as a sideman in someone else’s band, Surman’s performances never lack impact. His intensity and complete involvement with what he is doing are immediately apparent by watching him and such is his tremendous emotional projection that he sweeps his audience along with him so that their concentration on the music is no less a total experience than his own.

John comes from Plymouth. (It’s amazing the number of musicians this town produces: of the six men so far discussed in this series, three were born there – it must be the influence of that hot record store.) In 1961 he joined a band being run by Mike Westbrook at Plymouth Art School. When Mike moved to London he took John with him. ‘Things were difficult at first’, recalls Westy, ‘but gradually we were encouraged to go on, and became involved in a whole new movement in British jazz.’ Westbrook and Surman gradually gained themselves wide reputations.

The recording companies got the message towards the end of the 1960s. Westbrook’s ‘Celebration’ LP (1), recorded in 1967, marks Surman’s first appearance on record, both as soloist and composer. The highlight of the record is its final track, Portrait, designed by Westy as a special feature for John. The main theme is stated at the beginning by Mike’s piano. Second time round Surman plays the broad rhapsodic melody with the rest of the Concert Band filling in behind with some beautiful lush chords. By the third chorus Surman has moved away from the tune and is ruminating around its changes. The next two choruses are more assertive in nature, the rhythm section having slipped into double-time. The original mood and tempo are re-established as the brass play a counter-melodv to the first theme for two choruses. Howards the end of this the orchestration becomes denser and Surman returns, leading into a cadenza which appears to be drawing the piece to a close. A deft turn of phrase however shows that this passage is not a coda but a link between two sections. A fast modal solo follows (Surman plus rhythm) in which John gives a dazzling display of his technique: rapid runs which gradually give way to some piercing false upper-register notes. The rest of the band come in behind him, gradually destroying the beat and the tonality with wild cries of anguish and confusion. These subside, leaving the solitary baritone weeping in despair. An agonised chromatic descent leads to a rich chord from the band which tries to offer some comfort. We are back to the first theme again, though this time it has a bitter-sweet quality. Towards the end however we’re led to believe that all is well again as the original warmth and rich textures return. Surman’s last note though – a spine-chilling shriek – dispels any such optimism. A highly moving performance.

Other LPs with Westbrook followed (2) and (3), all of them very fine, and making extensive use of Surman’s baritone and soprano. A future article on Mike Westbrook will look further into this fruitful partnership. One feature that must be mentioned here though is the way Westy has utilised John’s extraordinary upper-register technique. By using harmonics he can play on baritone notes in the alto range. Such playing has a penetrating quality that cannot be produced by instruments within their normal limits. Some of the most exciting Westbrook scoring occurs when Surman, in extreme upper-register, rides above the whole of the band (e.g. as on Take Me Back (2)).

Another large group context Surman found himself in towards the end of the 1960s was Ronnie Scott’s Band. This was a more conventional setting than he was used to, but he sounded very happy in such surroundings. His soprano solo on King Pete (4), a fast blues, is a model of its kind. Mike Gibbs is a composer very much concerned with tone colour, and in John Surman he found just what was needed in his band, whether it be a delicate soprano solo for Sweet Rain or a big baritone sound for And On The Third Day (both on (5)).

Surman’s greatest work though is probably not with big bands but in the small groups he has led himself. Before discussing these though, mention must be made of one of those rare small group occasions when Surman appeared as a sideman instead of leader. Nominally John McLaughlin’s record, ‘Extrapolation’ (6) contains some exciting interplay between all four members of the quartet: McLaughlin (guitar), Surman, Brian Odges (bass) and Tony Oxley (drums). John’s own groups have ranged from a two-piece to an eleven-piece, and the first two records issued under his own name (7) and (8) show him working in a variety of contexts. He also had a fine octet which gave some tremendous performances in clubs and on the radio, but unfortunately this aspect of his work has not been released on record.

Last year he moved to Europe hoping to find more opportunity of playing than the British scene could offer him. He teamed up with bassist Barre Phillips and drummer Stu Martin, and his work in the trio has been his greatest achievement to date. The British tour and LP by this group (9) received enthusiastic reviews throughout the jazz world (see, for instance, Jazz Journals for April and September of this year for reviews of the tour and LP respectively). John uses his themes – usually simple riffy things, but often very catchy and memorable – as a reservoir which he dips into as a source for long, continuous improvisations. Note, for instance, the way he suddenly goes into the tune of Caractacus to conclude his solo which started from Incantation (9).

Surman has done great things, both for the baritone sax and for British jazz. When he moved to Belgium, Mike Westbrook gave a tribute to him on the radio, and I can think of no more appropriate way of concluding this article than by quoting from what Mike said. ‘I think John’s virtuosity, which is certainly impressive, is not important to him for its own sake’, suggested Westy. ‘It’s just natural for him to play with great facility, just as it isn’t for others, and his colossal technique and innovations on the saxophone are simply his personal vocabulary and what matters is what he is saying. For me John is essentially a romantic whose playing projects a great warmth and optimism, and exuberant rhapsodic joy, and at the same time a simple humanity – a sense of wonder and contemplation of the mystery of life.’

Recommended records:

1 Mike Westbrook Concert Band – Celebration (Deram SML 1013)

2 Mike Westbrook Concert Band – Release (Deram SML 1031)

3 Mike Westbrook Concert Band – Marching Song (Deram SML 1047/8)

4 Ronnie Scott and The Band – Live at Ronnie Scott’s (CBS 52661)

5 Michael Gibbs (Deram SML 1063)

6 John McLaughlin – Extrapolation (Polydor 2343012)

7 John Surman (Deram SML 1045)

8 John Surman – How many clouds can you see? (Deram SML 1045)

9 John Surman – The Trio (Dawn DNLS 3006)